The pitch was seemingly simple: a Hollywood movie about the national-championship-winning Michigan State University football team that integrated college football, with a historical book by the university’s academic press serving as source material.

It garnered big talent, with “Insecure’s” Ben Cory Jones in the director’s chair, “Yellowstone’s” Neal McDonough starring as head coach Duffy Daugherty, and TikTok megastar Bryce Hall in his big-screen debut.

Julian Horton, a former NFL player with a supporting role in the yet-to-be-released film, told an Atlanta talk show that he believes the film was so “meant to be” that it was “ordained by God.”

But, according to former players, historians, court filings and lawyers involved in the ongoing legal battles surrounding the production, what went into the film is far from holy: a book seemingly published in violation of the university press’ academic integrity policies, a slapped-together script rife with complete fabrication and racist tropes, and a conspiratorial criminal movie producer at the center of it all.

The film wrapped shooting in Georgia last fall, putting it in a temporary standstill as it seeks a distributor to get it in front of viewers with a theatrical release or sale to a streaming service.

Maya Washington, the daughter of Gene Washington, a hall of fame wide receiver featured heavily in the film, said it “smells of exploitation.”

“These are men in their late 70s, who contributed significantly to the history of the state of Michigan and to the United States, and went on to live private lives, with families, careers, children and grandchildren … they don't deserve to have had their legacies and contributions exploited or handled without real care,” she said.

Washington – who produced the 2018 PBS documentary and 2022 book, “Through the Banks of the Red Cedar,” about the team and their legacy – has repeatedly voiced concerns about the book and film to those responsible.

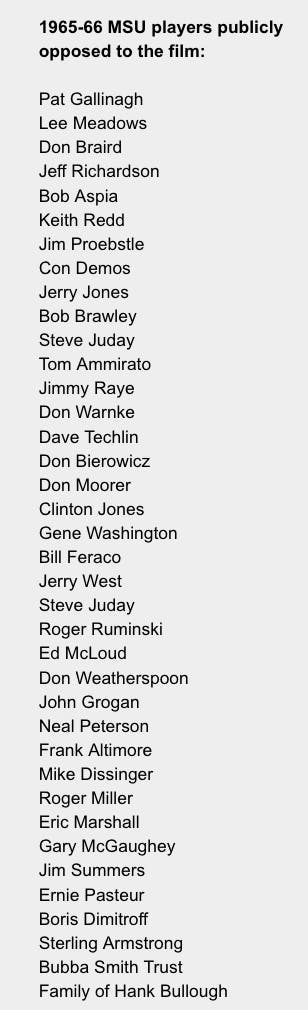

Today, Washington and a group of former players have lawyered-up, demanding a stop to the film’s looming release and an end to publication of the MSU press book it’s based on.

@thenealmcdonough I’m here to show YOU what it’s like being on a movie set! #movieset #movieproduction #nealmcdonough #yellowstone #bandofbrothers ♬ Just Wanna Rock - Lil Uzi Vert

What’s in the film

The State News could not obtain a copy of the script, but through the ongoing legal back-and-forth with the film’s producers, Washington and the former players were given an opportunity to read it.

Washington described the film as a “complete fabrication” comprised of countless “Hollywood tropes.”

She says it includes invented romantic subplots seemingly out of a “modern soap-opera,” wholly fabricated scenes involving former Michigan Gov. George W. Romney and American civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., and an invented white teammate whose “insatiable racism” drives him to attack a Black player and his girlfriend, leaving the latter for dead. The film then has Daugherty learn about the incident, but take no action, because the invented white player’s father is a donor to the team, Washington said.

In statements provided through their attorney, the players who reviewed the script also took issue with their portrayal.

Washington’s father, Gene Washington, a College Football Hall of Fame wide receiver, who also played in the NFL, said he “is disgusted and embarrassed by the false portrayal of me in the script and the attack on my reputation and that of my teammates and coaches.”

“I am falsely depicted as frequently partying – even drinking “jungle juice” – and offensively portrayed as speaking in broken and crude English when, in reality, I pride myself on a clean lifestyle, was driven and focused, and devoted my time in college to multiple sports, attending to my studies and carrying myself with class,” he said in the statement.

Bob Apisa, the first Samoan ever selected as an All American, said in a statement: “I am profoundly dismayed by my portrayal as nothing more than an ethnic stereotype.”

“The script depicts me as leading the team in a ‘Haka’ dance, which never happened, and which is a slight to all Maroians from New Zealand,” he said in the statement.

Jimmy Raye, who followed his time at MSU with 38 years of NFL coaching for ten teams, said “I object to the attack on my reputation by the portrayal of me as a subservient person lacking in independent thought and character … The essence of diversity and inclusion is completely missing from the script.”

The representatives of Bubba Smith, who played in the NFL before stepping into Hollywood acting, said in a statement that the portrayal of Smith in the film is “totally false” and “defamatory to him and to his friends at the time.”

In September 2022, as the film was shot in Georgia, the players sent a cease and desist letter to the cast and crew.

Days later, MSU’s general counsel released a letter clarifying that the university is not partnered with the film. The letter also advised the producers not to infringe on MSU’s intellectual property on threat of litigation.

Washington said the film is especially concerning given the current political climate in which she sees “people seeking to erase history, or rewrite and retell it.”

“There has to be some public expectation and standard that says: this isn't okay,” Washington said. “It does really disgusting and disturbing things to completely invent narratives of real people's lives.”

Despite the criticism, the producers defended their film, saying it “highlights the accomplishments of these heroes in an extremely positive light” in a statement released to Deadline.

The source material

The film purports to be based on the book “Duffy Daugherty: A Man Ahead of His Time,” which was published by MSU’s university press in 2018.

The book – authored by “nationally known business consultant, master methodist and motivational speaker” David Claerbaut – doesn’t include many of the allegedly fabricated plots featured in the movie, but its own integrity issues are where the problem started, Washington said.

Historical books published by MSU’s university press employ systems of citation which show readers where the information comes from. But, in Claerbaut’s book, the only references to source material are occasional “in-line citations,” where authors and their work are mentioned in the prose.

Georgia Tech Associate Professor of History Johnny Smith, whose historical scholarship on the integration of MSU’s football team is loosely referenced in Claerbaut’s book, said the lack of citations creates a transparency issue for readers.

“Maybe the author uses a great foundation of primary sources – newspapers, oral histories, new interviews, materials from the MSU archives – but because he didn’t document his work, it makes it difficult for us to understand where his information really comes from,” Smith said. “It makes it very difficult to follow the trail of information, it’s problematic.”

This lack of citation also leaves some passages of Claerbaut’s book within MSU’s definition of plagiarism, with numerous uses of quotes pulled from publications like the Lansing State Journal and Sports Illustrated without credit.

Claerbaut did not return calls seeking comment.

The press’ leadership denied requests for an interview, instead opting to answer questions through Deputy University Spokesperson Dan Olsen, who defended the publication of the book.

Olsen said the book differed from other works published by MSU's press because it's intended for the “general public" rather than an academic audience. He also said the book is not entirely a work of the academic press because it’s sold under the MSU Press’ “Greenstone Books” imprint, which the press uses to publish books for a “non-academic audience," Olsen said.

Claerbaut’s book is one of four currently sold under the imprint. The other three works all include citations.

Olsen defended the lack of citations, saying “you wouldn't have citations in a biography.”

Smith questioned that, citing his own experience writing biographies that include citations, saying that no matter the audience, “if you're writing history, you should always document your sources.”

“Whether you're a journalist, or a professional historian, or an amateur writer who's writing your first book, I think it's up to the publisher to uphold high standards of accountability to their authors,” Smith said. “So the readers who purchase the books can read them with confidence that it’s researched, thorough, and has integrity.”

Beyond the lack of citations, the book also wasn’t subject to the peer review and integrity investigation processes that MSU Press’ policy mandates for academic works, Olsen said.

Washington – who has repeatedly voiced concerns about the book’s historical integrity and broader “clumsy” handling of race in “offensive editorial commentary” – said she was “profoundly offended” by the press’ stance.

“I’m shocked and appalled that an institution of higher learning doesn’t have a higher standard,” Washington said. “The assumption that a general audience is not entitled to the same integrity and reliability of information is unacceptable to me … I believe that’s a very dangerous stance.”

With the film’s release looming, bringing a presumed bump in sales to the book it advertises as source material, Devin McRae, the lawyer representing Washington and the former players, said his clients would like to see MSU stop selling the book.

The university has said they don’t plan on another printing, but will continue selling the current run. McRae insists that what’s needed is a stop to all sales.

@thenealmcdonough Here’s the behind the Scenes! Want more? Let me know! #movieset #movieproduction #actorslife #actor #nealmcdonough ♬ BOOM - Tiesto

Further legal troubles

Beyond the ethical concerns with the content of the film, legal issues burden one of the film’s producers – James Velissaris, a former college football player, now-disgraced financial professional, and Claerbaut’s step-son.

Velisarris - who co-wrote the film’s script based on his step-father’s book and funded much of the production – is being sued civilly in Georgia by members of the Black Spartans crew who allege they worked 90-hour weeks without overtime pay and were left unpaid all together for the final month of filming.

That litigation stalled in April, when Velissaris was sentenced to 15 years in prison for various financial crimes unrelated to the movie at his now-liquidated firm “Infinity Q.”

The criminal indictments – coming from grand juries in New York and Georgia and covering numerous financial crimes including securities fraud, wire fraud, and conspiracies to obstruct the SEC investigations into those frauds – seek tens of millions of dollars in restitution in addition to the prison time, according to court documents. It’s possible that through a “substitute assets provision” in the indictments, the federal government could be entitled to Velissaris' Black Spartans earnings.

The federal prosecutors who charged Velisarris and the criminal attorneys who defended him did not return requests for comment. Due to his incarceration, Velisarris could not be reached directly.

The lawyer representing the allegedly unpaid Black Spartans crew, Michael Schoenfeld, declined to comment on how Velissaris’ owed restitution could complicate the crew’s case, saying the matter is “ongoing.”

Where it stands today

The film is yet to find a path to release. Interest has been expressed by an executive at Sony Pictures, according to emails obtained by The State News between Washington and the MSU offices of the President and General Counsel, but nothing is concrete.

Without an indication of where and how Black Spartans will manifest, Washington, her father and his teammates are left dreading further “exploitation of their legacy.”

“Unknowing people who will see it are going to think ‘oh, this must be true,’” Washington said. “Because why would someone completely make up another person's life story? And why would it not be true, if it's based on something that a university published?”