The then-candidate, who will begin a second term in office in January, canvassed door to door, handing out campaign literature with photographs of her family on it — and the response always was the same.

“I recall people being like, ‘Who’s going to watch these kids?’” Erwin Oakes said. “No one ever asks a man when he’s out campaigning, ‘Who’s going to watch your children?’”

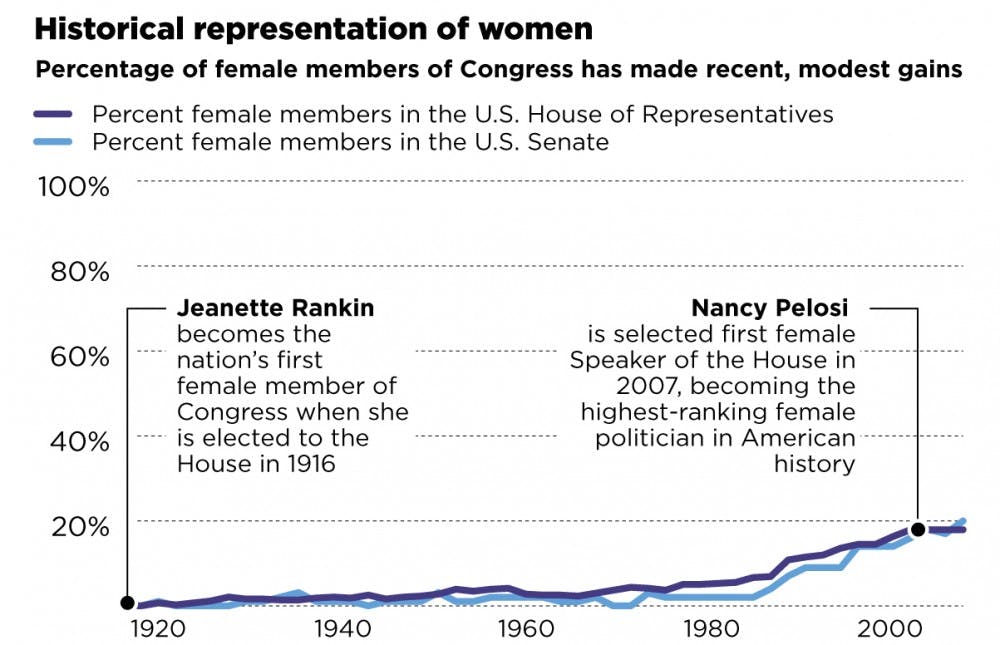

Women will hold 21 percent of the seats in the state House in the next term — the highest of any state or federal house. But it still is far short of the national population ratio between males and females, which is split nationally at 50.8 female and 49.2 percent male, according to 2010 Census data.

Women picked up three seats each in both the U.S. House and Senate, marking historic highs for both houses.

Beginning in 2013, 78 women will serve as U.S. representatives and 20 women will be U.S. senators — including Sen. Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., who was up for re-election this year.

But women in the state Legislature did not fare as well, losing two seats in the state House, dropping the total to 23, and remaining stagnant at four women in the state Senate, which did not hold elections this year.

Erwin Oakes said now that she has served in the state Legislature for almost two years, she has seen diversity increase in the Capitol, but it’s not enough to even out the disproportion between total women in the U.S. and women who hold public office.

“As a woman, I want to see more women get involved in the process and, again, to not accept the status quo,” Erwin Oakes said.

Traditional roles

Women have made advances in politics in the past century, steadily increasing their representation, said Jayne Schuiteman, interim director of the MSU Women’s Resource Center.

But when it comes to women’s rights, the U.S. seems to take a few steps forward, but always falls back again — which is nothing new, historically.

“Our country was founded on the idea that men are created equal,” Schuiteman said. “That never meant men and women.”

Schuiteman noted American politics is dominated by white males and is slow to change.

“People don’t want to give up the power that they have,” Schuiteman said. “(They) will work very hard to keep the people with less power in that position.”

Seeing mainly men in leadership positions makes it more difficult for young women to envision themselves in similar leadership roles, said Herasanna Richards, a communication sophomore and the publicity manager for the MSU Vagina Monologues.

“Many times, if you refer to a leader, it’s ‘he’ or ‘him,’” Richards said. “So it’s hard (as) a girl to picture myself in that (sort) of a position, too.”

Fighting for a voice

Maria Bruno, an associate professor in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric and American Culture, said it was apparent in this year’s presidential election that women were standing up for what they believed in and making strides toward change.

But however slow the progress is, things are getting better, Bruno said, noting the significance of women voters in re-electing President Barack Obama and ushering in the record 20 women in the U.S. Senate.

In the final weeks before the election, the presidential candidates heavily courted women voters, knowing their potential to impact the results, especially this year, when numerous bills concerning women’s health have appeared across the country.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

In Michigan, a package of anti-abortion bills passed the House and a Senate committee this summer, but not without considerable backlash from abortion rights supporters, including Lori Lamerand, the president and chief executive officer of Planned Parenthood of Mid and South Michigan, who called the bills the worst in the country for women’s rights.

Bruno said these bills and other comments from Republican lawmakers concerning rape and abortion have caused women to rise up and speak out.

Incoming state Rep. Sam Singh, who recently was elected as state representative for the 69th district, has said he believes in respecting women’s rights and does not support the anti-abortion bills, criticizing the legislators backing it for bringing a personal issue into the state Capitol.

“A woman and her doctor should make (those decisions),” he said in a previous interview. “The government shouldn’t be in the middle.”

ASMSU Vice President for Academic Affairs Emily Bank, the only woman on ASMSU’s executive board, said male-dominated legislatures have been in control of decisions on women’s issues, which is problematic.

Richards said only women should decide what is best for their health and lives and that such decisions should not be left up to male lawmakers with less at stake.

“No one (who) isn’t in the position of a woman has the right to say that this is the end-all position,” she said.

Political potential

During the next few decades, Schuiteman expects to see further progress in women’s rights, a repeat of history from a similar backlash from women in the 1980s.

Leading into the next legislative term, state Rep. Marcia Hovey-Wright, D-Muskegon, said she was pleased with the strength of the women who were elected earlier this month, but historically, women always have been outnumbered by men in the Legislature.

“Men don’t seem to need to be asked to run, but women do,” she said. “They need that assurance or encouragement because it’s sort of a new thing for women, and we just need more women to believe they can do it.”

On campus, Bank said there generally are equal opportunities for women and men to obtain student leadership roles, but the gender gap elsewhere is something she is conscious of as a woman.

There are too few females in authoritative roles for younger girls to look up to, Bank said.

“I see it as a slow progression,” Bank said. “Women have had many stereotypes all this time, so it’s going to take time for women to kind of gain more power and have their place in politics.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “Leading the Charge” on social media.