Hendrik Schatz studies exploding stars — or more specifically, what connection exploding stars have to our planet’s existence and the existence of elements on Earth today.

He suspects that about 15 billion years ago, stars either exploded or collided, sending radioactive particles into the universe. Eventually, these radioactive particles became stable, clinging together to form Earth and many of the elements we use today, such as gold and uranium.

“All the elements heavier than iron, we don’t understand how nature actually made them,” said Schatz, a professor at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory, or NSCL, located on campus. “Why is there uranium? It’s all a big mystery.”

Although it is impossible to know for sure if Schatz’s theory about elements coming from exploded stars, which is in line with the Big Bang theory, is accurate, through research done at NSCL, scientists are getting closer to figuring out just what happened billions of years ago.

But age is a major issue, as the NSCL eventually will become outdated, causing MSU to pursue the funding and construction of a new nuclear physics lab called the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams, or FRIB. FRIB (pronounced eff-rib) is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, or DOE, and will allow scientists to accelerate common elements to roughly half the speed of light and back to their radioactive states before they became stable elements. Although the NSCL allows scientists to do something similar, FRIB can speed up the isotopes, or elements, to faster speeds using an accelerator, slow them down so scientists can study the isotopes that generally are able to stay in the targeted state for less than a microsecond, and then speed them back up — the first lab of its kind in the world, FRIB Project Manager Thomas Glasmacher said.

But the amount of funding for FRIB is uncertain, and with other countries racing to develop technology on par with FRIB, the U.S. will need to work quickly and watch their backs if they want to be the first country in the world to have a first-of-its-kind accelerator.

Funding frenzy

The total cost of FRIB is projected to be about $680 million, including a 30 percent contingency accounting for changes in cost and inflation, and has a completion date estimated in 2021, Glasmacher said.

But determining exactly how much funding FRIB will receive every year is difficult to predict because the DOE’s budget is determined by Congress each fiscal year, he said.

Funding determines the speed at which the project can be completed, and with a revolutionary accelerator like FRIB’s, time is of the essence if the U.S. wants to create the first accelerator of its kind.

“The DOE and the people who give us the funding also don’t know what their funding is each year; so even though we have a plan, sometimes the plan changes,” Glasmacher said. “There was the recession of 2008, and there is less money available now.”

FRIB likely will receive between $30 and $40 million this year, after several different recommendations from the executive and legislative branches ranging from $22 million to $40 million.

U.S. Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Brighton, a proponent of funding for FRIB, said he will be pushing for FRIB to continue to receive funding and remain a national priority.

“I was proud to advocate on behalf of FRIB that it receive $40 million in House funding, despite an administration request and Senate appropriations that came in below the agreed-upon amount between the Department of Energy and MSU,” Rogers said. “The Energy and Water Appropriations bill will next go before a House-Senate conference committee, where I will continue to advocate that the funding that I facilitated remain intact.”

Glasmacher said he does not expect the funding for FRIB for 2013 to be announced until after the presidential election in November.

“Like any project, $40 million would be ideal, but $30 million is also good,” he said. “We re-plan once we know our funding.”

FRIB developers will likely hold a planning meeting to re-evaluate the project after funding is announced — the last planning meeting was held in 2007 before the 2008 recession — to determine future plans for the project. Ideally, construction will begin close to March 2013, he said.

Andrew Hutton, associate director of the accelerator division of Jefferson Lab, another lab funded by the DOE that is assisting MSU in building the new accelerator for FRIB, said currently FRIB will hold the first accelerator of its kind, but because of the recession, other countries that can fund similar projects more quickly might catch up and produce this type of accelerator first.

“(The U.S.) better look over their shoulder because the Koreans are proposing a machine that is similar, and elsewhere in the world, there are other places that are interested in building their own accelerators,” Hutton said.

Korea is willing and able to put more funding on the line to catch up to the U.S., he said.

Korea has the funding, and the U.S. has the skill.

But Hutton said it isn’t as though there is some big nasty buzzard taking away the money for FRIB — there just aren’t sufficient funds to support science from the government at the moment.

“This is an area where the U.S. could be world-leading if funding continues to arrive,” he said.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Creating community

But regardless of whether the U.S. ends up being the first country to have an accelerator similar to the one in FRIB, MSU still has NSCL, a facility that currently draws in users from 55 countries, mostly Europeans, and users from six continents.

Any user can apply to use the accelerator, currently part of NSCL.

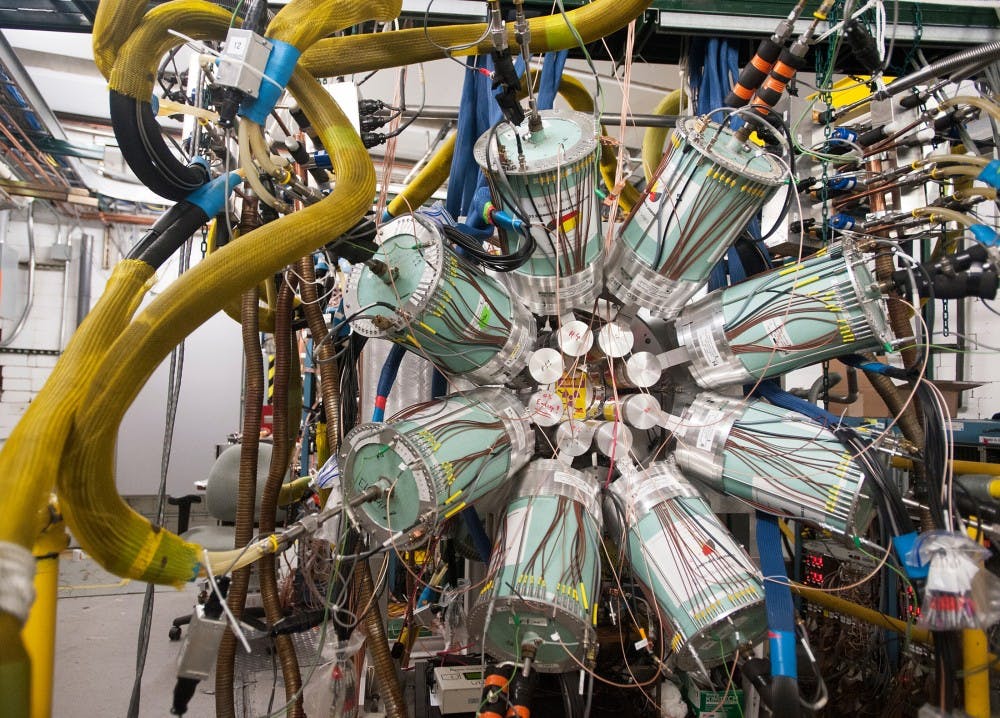

According to FRIB Communications Manager Alex Parsons, from 2001 to the end of 2011, 195 experiments recommended for beam time by the NSCL Program Advisory Committee and granted beam time by the NSCL director were completed. Overall, NSCL has over 1,200 registered users.

Once FRIB is built, a majority of the equipment used in NSCL will be engulfed in the new facility.

Its world reputation and promising future is what first drew Andrew Klose, a graduate student and nuclear chemist at NSCL, to come to MSU, Klose said. Before meeting an MSU professor at a conference in New York as an undergraduate, he mostly knew of MSU for its sports. Since coming to MSU, he said he likes to have the chance to work with users from across the globe each day, which has provided him with networking opportunities, and he feels the lab has a promising future with FRIB.

“One of the major benefits of working at NSCL here is that it is a world-class facility, and you get hands-on experience of being (here),” Klose said. “But what’s also nice about being here is that a lot of visitors come, and you’re the resident expert in how the detector or how this and that works, and you get involved in a lot of those experiments with outside people.”

Glasmacher said one of the things he finds most interesting about the future of nuclear physics at MSU, particularly dealing with FRIB, is the way people come together to work on something completely new in a place such as MSU, which has so much history with many older buildings.

“More than 200 people can come together and build something unique that has never been done,” Glasmacher said. “MSU has been around so (long), and we’re going to have FRIB, (which is) really new, and we’re going to have the new (Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum) in the fall, which is really new looking, so it is changing. But there is also a lot of history, so that just kind of spans the whole thing.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “When a star explodes” on social media.