Battling seasonal depression

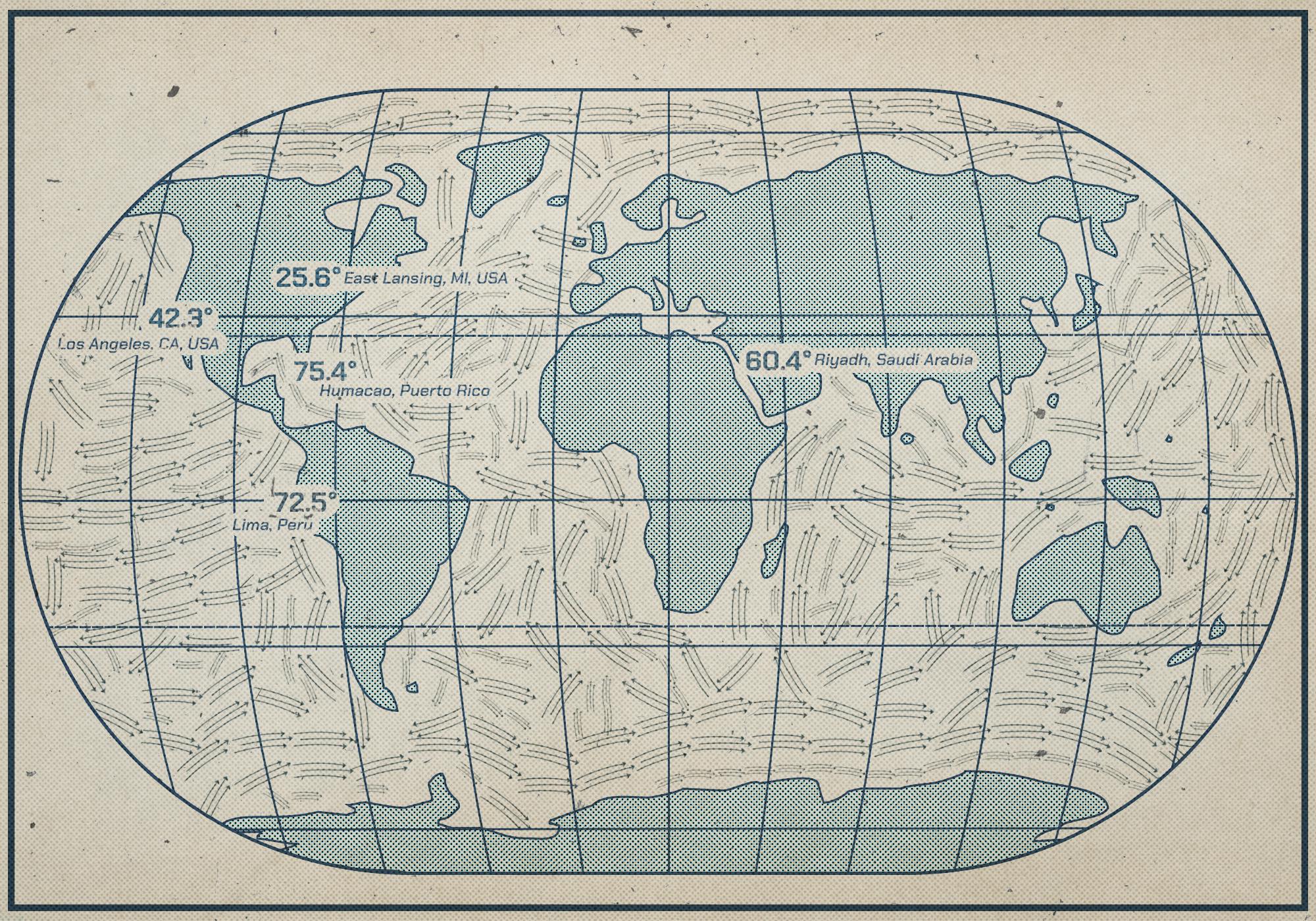

Thuria Alammari, a senior majoring in media and communications with a minor in business, has lived in several places in the US, including Illinois, Minnesota, and Washington. She visits her home in Saudi Arabia nearly every winter and summer break, and coming back isn’t always easy. Back home in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, average winter temperatures sit at about 60° F.

“[For our last break,] I went back to Saudi and then I came back [to Michigan],” Alammari said. “I was crying because it was so cold.”

Alammari said she started experiencing seasonal depression after moving to Michigan, which usually starts right after daylight saving time.

“With the day shorter and with the sun setting sooner, it makes me not want to do anything,” Alammari said. “I've always loved summer more, but I think now I hate winter more than ever.”

Even for someone who has experienced winter weather in other states, Alammari has been blind sighted at times by the severity of Michigan winters.

“I didn't do much research on the weather before coming here. I should have, but I just kind of in my head was like, yeah, I've dealt with winters before, so it shouldn't be that bad,” Alammari said. “It makes me sad, like, I wish I chose a school in Florida or something.”

An extra-intense climate

One unexpected contributor to Michigan’s weather is the Great Lakes. Known as the lake effect, cold air flows across the warm air emitted by the lakes, forming storms that can produce three or more inches of snow per hour.

Lorenzo Uccelli, a senior majoring in Agribusiness management, also found himself misled about and unprepared for winter weather conditions. For him, 72° F winters in Lima, Peru, are the norm.

“The first time I came here, I felt like spring semester was supposed to mean that it was going to be sunny and hot. So, I traveled from Peru wearing shorts and Crocs,” Uccelli said. “I arrived at the airport, and I realized it was very cold.”

Uccelli said the weather really started to impact him last fall. Without gloves on, he biked to his 7:00 am exam in the snow, enduring the painful burning sensation on his hands that Michiganders know all too well.

At the midpoint of this winter season, Michigan saw more than half of the average amount of snow typically seen in one season. On top of that, wind chills have reached record highs in some areas.

The National Weather Service reports that Michigan is facing the most intense blasts of Arctic air since the polar vortex of Jan. 2019. Climate change is quickly warming the Arctic, lowering the difference in temperature between the bodies of air in the Arctic and in Michigan. This results in these bodies of air mixing, allowing the polar vortex to dip into the US and dropping temperatures significantly.

“My first spring semester, it wasn't that cold when I arrived, but it started getting colder,” Uccelli said. “Right now, with the Arctic storm, it’s getting colder than I thought it was going to be.”

Uccelli emphasized how difficult it was to endure the cold for early morning classes; having to walk before the sun had risen because the buses were full made it increasingly difficult to attend class.

“The worst part was that all my classes as a freshman were like 8:30 a.m. because I didn't know at first that it was going to be that cold. When I woke up and I thought about having to walk in the cold weather, I just wanted to stay in bed instead of going to class,” Uccelli said. "I remember in some classes I didn't do too good because it was cold and it was very early, I was sleeping in class or watching YouTube videos instead of paying attention.”

University increment weather policy

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

The university’s policy for cancelling classes due to inclement weather has been a point of major contention recently, with many students and professors hoping for a clearer policy due to various safety issues.

Rosa O’Connor Acevedo, assistant professor of philosophy at MSU, voiced her concerns about this, saying that the cutoff for cancelling class isn’t always clear for her as someone who is from Puerto Rico and has only experienced winters in Massachusetts and Oregon.

“There's a lot of uncertainty for me, being a new faculty member on my first year, not used to this weather, to know what to do if the conditions get really bad,” O’Connor Acevedo said. “What should I do if there's not a clear policy, if there's not a threshold? So, I feel like I have to come [to class] no matter the conditions if the university says they’re continuing operations.”

She said one of the most stressful things for her has been learning how to drive in snowy or icy conditions. Worries about the cold temperatures affecting her students’ health while walking to class also sit at the back of her mind, as she anticipates a day when she will have to hold class despite extreme conditions.

“I don't really feel comfortable with that idea,” O’Connor Acevedo said. “I wish the university would have a clearer policy to provide options for online classes.”

For MSU, there is still no official university snow day policy, threshold for when to cancel classes or guidelines for alternative class modalities such as Zoom.

Winter's impact on physical activity

Although O’Connor Acevedo loves teaching, doing research, and interacting with students and colleagues, she feels that much of her experience of Michigan has been centered around work, with limited time outdoors affecting her physical and mental health.

“Puerto Rico and Oregon were places where I could connect with other people and with nature that were healthy ways of releasing stress. I feel like that is definitely missing here,” O’Connor Acevedo said. “I feel a bit disconnected from the Lansing community and East Lansing in general.”

Above all, O’Connor Acevedo said she feels the biggest impact on her health comes from not being able to exercise outside.

“When I am not exercising and just working, I think I accumulate more stress, which affects my mental health. It can increase anxiety levels regarding work, and it can increase irritability too,” O’Connor Acevedo said. “That also contributes to more exhaustion towards the end of the semester.”

According to a 2025 study published by the National Institute of Health, there are potential added benefits to exercising outdoors compared to indoors, such as lower levels of perceived exertion, higher perceived enjoyment, reducing stress, and improving mood.

Unable to follow her normal exercise habits, O’Connor Acevedo also noticed her energy and motivation levels were much lower.

“When I'm working, I'm here, but the moment I don't have to work, I just don't want to be here,” O’Connor Acevedo said.

Orlando Hawkins, a James Madison assistant professor in political theory and constitutional democracy, is also experiencing his first year living in Michigan. Having lived in New York and Oregon, and growing up in Los Angeles, California, where winters are 42° F on average, he was used to walking outside as his form of exercise.

“I feel like being an academic involves a lot of sitting, generally. If I'm in my head all the time, it would be nice to move my body a little bit. I would like to walk around to get some exercise, but because of the weather, I find myself indoors more,” Hawkins said. “Before I teach a class, I will sometimes do a walk around the block. That’s something I was doing in the fall, which I'm not doing currently.”

Like Acevedo, Hawkins has struggled with his motivation when he’s not consumed by work.

“Motivation-wise, it's fine, as long as I'm not home,” Hawkins said. " I feel like if I'm here working, if I'm out of the house, because I'm busy, my mind is distracted. So, I don't feel the need to have to cope [with wintertime], unless that would be a form of coping.”

Isolation in the cold

Especially during breaks, many suffer from the loss of mental stimulation that the semester brings. For her sophomore year winter break, Alammari had to stay in her apartment alone for four weeks.

“It was one month of me just not being able to do anything. I couldn't do anything,” Alammari said. “I went to downtown maybe once, and the rest of the days I was just inside.”

She said when she experiences bouts of seasonal depression like this, she tries to cope by finding things she likes to do indoors.

“I was trying to do things to hype myself up. I would do my makeup and take pics,” Alammari said. “I've been trying this thing where I do yoga in the morning, and I just create a vibe for myself in the morning so that when I leave my house, I'm not depressed.”

In the US, about 5% of the population experiences seasonal depression, primarily those in Northern climates. In a 2024 poll by the American Psychiatric Association, half of Midwesterners said their mood declined in the winter, the highest of all US regions polled.

“Right now, I feel like I'm pushing through every day, even though I don't want to, but I don't have another choice,” Alammari said. “So I just have to put on a smile and do what I need to do. I have to finish my degree.”

Uccelli and Hawkins both emphasized that even in the cold weather, they believe that if you put your mind to something, you can adapt and push through using the resources available to you.

“Human beings, we are very adaptable. We can adapt to many different situations and weather, not only mentally, but physically,” O’Connor Acevedo said. “I try to think, well, this is a new experience. I didn't grow up in this weather. I try to appreciate the difference and not compare it.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “Heat-acclimated MSU students and faculty adjust to Michigan winters” on social media.