For the modest few who gathered that Friday afternoon, the talk was about educating listeners on the niche artistic realm. For the Associated Students of Michigan State University, it meant something vastly different.

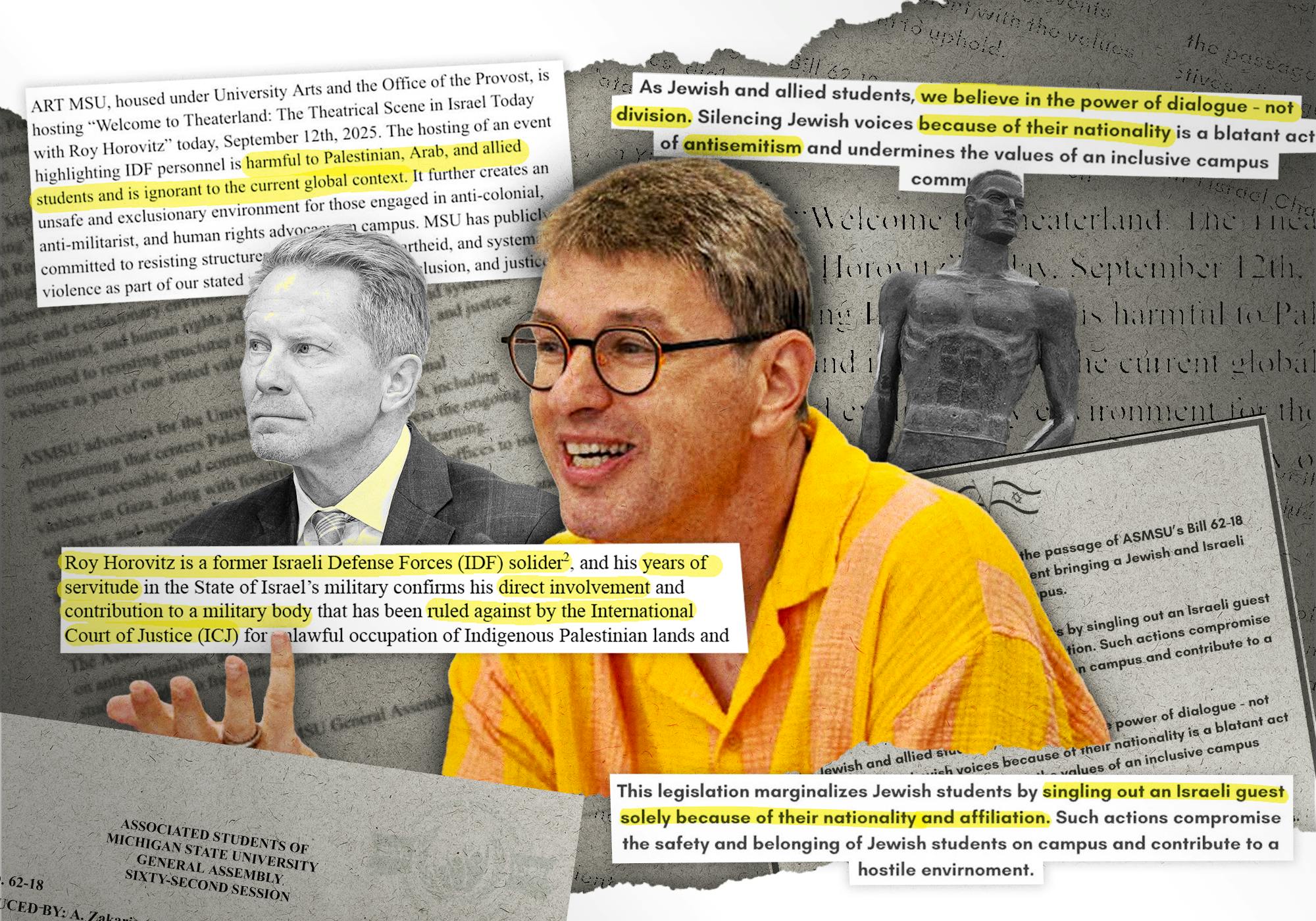

A student government resolution, hastily passed the night before, described the event as “highlighting the work of Israeli and IDF personnel.”

Horovitz, like most Jewish Israelis, had been required to briefly serve in the nation’s defense force after he turned 18. So, the university was, in effect, hosting “individuals affiliated with ICJ-condemned military bodies that are found to be committing genocide,” according to ASMSU’s resolution. It ran the risk of retraumatizing Palestinian and Arab students, it argued.

A petition circulated amongst students, demanding the event be canceled, asserted that Horovitz’s visit was “particularly distressing for MSU, a campus still healing from its own trauma, and one which stands on Indigenous land.”

The event’s most vocal critics saw the mere presence of an Israeli on campus as a threat to the principles MSU upholds. But some in MSU’s Jewish community view that framing as discriminatory by nature. They say it's more nuanced, and that writing off an entire group of people due to the actions of their government is simply antisemitic.

Such are the zero-sum politics on MSU’s campus today. Intense polarization, entrenched moralism and eagle-eyed perceptions of bias reign supreme, even as the university’s president has looked to lower the temperature, making a series of lofty pronouncements about “civil discourse.”

An ‘urgent’ concern

A few days before the event, Professor Yael Aronoff’s email inbox started flooding with messages urging her to call off Horovitz’ lecture. Aronoff is the director of the Michael and Elaine Serling Institute for Jewish Studies and Modern Israel, which hosted the event with MSU’s Department of Theatre.

The inundation was itself curious, she said — but more so was the fact that few of the emails were from MSU addresses, instead coming from people affiliated with Wayne State University and University of Michigan. Furthermore, the language used in most of the emails was nearly uniform.

Her LinkedIn account was also seeing unusual levels of activity, Aronoff said. She got a notification that 100 people had viewed her profile.

Those messages directly to Aronoff were seemingly just one piece of a broader campaign. She said the Department of Theatre chair, the dean and the provost were receiving similar messages.

The State News obtained an email petition circulating among student groups in the days leading up to the event. The person who shared it did so on the condition that they not be identified. The petition included blanks so that student groups could sign on, and called on MSU to cancel the event. It listed email addresses for Aronoff and the other administrators, and instructed people to send them copies of the petition. It was marked “urgent.”

It said MSU’s hosting of a cultural event featuring a former member of the IDF, without acknowledging “Palestinian suffering,” was an affront to the university's values. And, it “risks normalizing and sanitizing a state apparatus currently under global scrutiny for grave human rights violations.” It also argued that if the university wants to engage with Israeli or Palestinian culture, the programing must be “balanced”.

That claim is particularly frustrating for Aronoff: the Serling Institute has invited several Palestinian speakers to MSU in recent years. In fact, Aronoff said the department has an event scheduled for late October, which will feature both an Israeli and Palestinian speaker.

“But it also, of course, doesn’t mean that every single one of our events is going to feature Palestinians," she said.

It’s unclear where the email template originated. The State News reached out to several student organizations that have been vocal about the Israel-Hamas war; all of them either didn’t respond or declined to comment.

On Friday morning, the day of the event, Aronoff got another email. This time, it was a member of ASMSU, writing to say the student government had voted the night before to advocate for the cancellation of Horovitz’ lecture, and asking her to respond. She didn’t.

“Not because I don't care,” Aronoff said. “It's just, I think it's hard to have a dialogue over email.”

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

ASMSU’s bill echoed many of the concerns of the petition. It claimed that the event highlights “the work of Israeli and IDF personnel." Doing so “normalizes relations with violent states and erases Palestinian and Arab suffering”.

Aronoff finds the bill — particularly its focus on Horovitz’ IDF service — concerning. Given that Israeli law requires the majority of its citizens to serve in the military, the bill’s logic would suggest that, to ASMSU, “most Israelis aren’t allowed to speak at MSU,” she said. That constitutes “discrimination based on national origin.”

It also has grave implications for academic freedom, Aronoff said. She finds ASMSU’s bill to be antithetical to the concept — that scholars should be able to express their ideas freely, and campus discourse should be tolerant of a wide range of views.

Bill’s inception

Aesha Zakaria found out about Horovitz’s visit a day earlier. The psychology senior, who represents the Asian Pacific American Student Organization on ASMSU, was shocked: the event goes against years of advocacy from not just Muslim and Arab students, but ASMSU itself, she told The State News. It was evidence of MSU’s continuous ties to Israel, she said — a country that she noted has been accused of war crimes by the International Court of Justice.

“That's why I felt really compelled to write a bill and advocate for the cancellation of the event,” Zakaria said.

After studying for a quiz, Zakaria started researching Horovitz and drafting her bill. It was tricky: the playwright has a minimal social media presence and most of his public appearances and media interviews are just about theater, she said.

Then she found a stray line in a comparative Jewish literature anthology that includes a memoir written by Horovitz. In it, he details his rise as a scholar and actor, saying, “To fulfil this dream, I had to first finish my military service.” (Conscription is required of Jewish Israelis over 18.)

For Zakaria, it was a smoking gun: “That makes him complicit in the genocide that has been happening in Palestine for the past several decades,” she said. While she acknowledges that conscription is mandatory, “that does not excuse complicity in the crimes that have taken place in Palestine.”

With that, she had her bill. The problem was timing. The event, which she hoped to see canceled, was only a day away. There was an ASMSU meeting in a few hours, but the agenda was already set.

Still, Zakaria sent the bill around to other representatives, she said. Some promptly signed on as co-sponsors. And, a common ASMSU practice would allow them to bypass the typical committee approval process: they could suspend the rules of procedure to force a vote on the bill that night.

‘A dangerous message’

Jewish Student Union representative Vladimir Shpunt found out about the bill when it was sent in the ASMSU group-chat, just an hour before the meeting. He panicked as other representatives said they planned to introduce it with a suspension of the rules.

“I had about 20 minutes to write a speech, including research, because I had to drive there,” Shpunt said.

Shpunt was the only one in ASMSU’s general assembly to vote against adding the bill to the agenda. A motion to have a recess to discuss the bill further also failed. Instead, the room moved into formal discussion with Zakaria’s opening statement.

She reiterated the framing that had burgeoned in the days prior: The event would harm Arab and Muslim students by bringing someone to campus that served in a military participating in violence against Palestinian people. Zakaria said the goal was not to remove Jewish spaces from campus.

“I believe that this event does not necessarily serve Jewish spaces as much as it just naturalizes and normalizes Israel's presence and ties to this campus,” she said. The bill’s seconder, James Madison College representative Abe Jaafar, spoke next, echoing Zakaria’s argument.

Then Shpunt, the JSU representative, got to speak. He said the bill violated ASMSU’s commitment to civil discourse by singling out a Jewish and Israeli actor set to speak about his culture through art, rather than discuss policies or ideology.

Shpunt compared the event to a recent Palestinian art exhibit present at the Eli-Broad Art Museum. When that display opened, Jewish students on campus did not protest or condemn the display, he said.

“Yet today you are asked to condemn a Jewish Voice before he even speaks," Shpunt said. "That is blatant antisemitism."

A representative then moved to override any remaining discussion and simply vote on the bill. That vote failed, and they continued to debate.

“Elevating such an individual sends a dangerous message,” said Muslim Students Association representative Sanaa Bashar of Horovitz. “This is not someone students should ever be asked to view as a role model, or learn from.”

After discussion concluded, they finally voted on the bill. It passed with fourteen in favor, five abstaining, and only Shpunt voting against.

JSU Vice President of External Affairs Tyler Pohl said the bill sets a dangerous precedent for student government. Rather than just advocating for something students believed in, it minimized his community’s presence on campus.

“It's become this political theater, almost, in a way,” Pohl said. “They bring up bills to make comments that don't necessarily directly affect the undergraduate student population.”

Reflecting on the bill, Zakaria said it wasn’t necessarily about Horovitz himself. Rather, it aimed to push back on connections between MSU and Israel. The goal, she said, wasn’t to make Israelis feel unwelcome on campus.

ASMSU President Kathryn Harding declined multiple requests for interviews over the course of a week, saying she was too busy. She also declined to answer a list of written questions. In a written statement to The State News, she said that her position as president is that of an unbiased mediator, and that it isn’t her place to influence individual bills.

This bill aimed to address the “perceived tone-deaf nature to Arab, Palestinian, and allied students with MSU hosting this particular event,” she wrote. She noted that ASMSU condemns antisemitism, citing a bill passed earlier this year addressing its relevance on campus.

University spokesperson Emily Guerrant told The State News that MSU doesn’t take a position on bills passed by the student government, but is working with the groups involved and impacted by this legislation.

“We affirm the importance of free expression, civil discourse, and the exchange of diverse perspectives, while also emphasizing that respect and care for one another must guide how those conversations take place,” Guerrant said in a statement.

The campus debate comes as the Trump administration watches universities closely for conduct it deems antisemitic. It has justified slashing millions of dollars in research funding to universities for their perceived blase attitude toward discrimination against Jews on campus. Some institutions, in turn, have vowed to address those concerns as a condition of their federal funding being restored. MSU has, thus far, stayed above the fray.

‘Cancel me?’

In the days leading up the event, Hebrew Studies Professor Yore Kedem was asking his students if they planned to attend. Some said they didn't plan to — but not because of a lack of interest. They feared the event would be met with protest or even violence, he said.

Kedem was disappointed by the controversy. He lived in Israel for 26 years, and completed his mandatory conscription. Kedem said he’s responsible for his own deeds, not the military’s. To him, protesting a group of people solely because of the actions of their government, one that he himself disagrees with, is "preposterous."

“I didn't choose to be born Israeli,” he said. “I am Israeli, and a very significant part of my identity is Israeli. But is that a good enough reason to cancel me? If that's a good enough reason to cancel me, then there's no other way to call it but antisemitism and racism.”

The actual event proceeded uninterrupted. Horovitz was introduced, then gave a lecture on Israeli theater. He talked about history, how the theater scene evolved, and some Israeli playwrights he admired.

Briefly, he did address the conflict.

“We navigate through an ongoing, harrowing, situation,” he told the small crowd. “War — terrible government from our side as well. I won't hide my opinions. We are really facing some harsh reality, both us and our neighbors.”

He added that this lecture, in part, would show that Israeli theater and its artists have their own voices, separate from their leaders. One play Horovitz read, “How to Remain a Humanist after a Massacre in 17 Steps”, was written days after the October 7, 2023 attack and centers on how to, as Horovitz puts it, "maintain humanism" after a tragedy and stick to compassion.

After the event, The State News asked Horovitz about the surrounding controversy. He said he came to MSU only as an artist; if anything, he aimed to bridge gaps between people through dialogue.

“People aren’t representatives of their governments,” he said. “Coming here, I would have taken everybody as a Trumpist. I know it's not the situation.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “‘Political theater’” on social media.