Jerielle Cartales has always been "a bones person." Growing up, she used to collect roadkill and watch it decompose in her family garden.

"As any normal, well-adjusted child should," Cartales quipped in a Giltner hall classroom last week, as she sat next to a cabinet full of — you guessed it — bones. Human skulls, to be exact, some models and some the real thing, that she would casually pick up to punctuate explanations of skeletal growth.

Perhaps that’s why the Michigan State University forensic archaeology PhD student didn’t squirm as she held her latest research subject: a one-foot-long mummified creature with skin the color of burnt paper, dried strings of intestine coming out of its backside and a mouth full of sharp, white teeth.

"He’s very cute," she said.

The cadaver — as well as a disembodied head that was found near it — has been an enigma ever since it was discovered in 2018 in the ceiling of Cook Hall during renovations. It was sent for a deeper look to the Campus Archaeology Program, a group that protects and investigates campus’ archeological findings, and has stayed there ever since.

Aside from giving it the nickname "CAPacabra," a combination of the program’s acronym and the blood-sucking cryptid known as a chupacabra, no one bothered to look into it.

That is, until Cartales came along.

As a first-year fellow with the Campus Archaeology Program, Cartales wanted a project outside the "dirt or small pieces of metal" often studied by the program. Given her love of bones, a colleague suggested she might be interested in the CAPacabra.

PhD student Jerielle Cartales holds a mummified creature in the forensic anthropology lab in Giltner Hall on April 8, 2025. The creature was found in the roof of Cook Hall during renovations in 2018, researchers are now trying to identify it.

There are a lot of unknowns about the creature, some of which Cartales is starting to untangle.

For starters, it’s unclear when the animal was last alive. It might have died in Cook Hall over a century ago, after the building was first built. But mummification can happen quickly under the right circumstances, so it also could have been "way later," Cartales said.

Mummification happens naturally when an animal is subjected to very dry conditions and stable temperatures — think Otzi the iceman, or roadkill lying out in the sun. Cartales said she wouldn’t be surprised if the CAPacabra was found next to an air duct or a heater.

A mummified creature lays on the x-ray table in the forensic anthropology lab in Giltner Hall on April 8, 2025. The creature was found in the roof of Cook Hall during renovations in 2018, researchers are now trying to identify it.

The biggest mystery, though, is what species it is. When it was found, the Campus Archaeology Program’s best guess was opossum. But Cartales’ preliminary visual comparison of the CAPacabra’s head to X-rays of opossum skulls scratched out that idea, since the creature has sharper teeth and a flatter snout.

Cartales’ review did introduce two new possibilities into the mix: raccoon and dog.

"We were just throwing ideas at the wall to see what would stick," Cartales said. "What is small with four legs and a tail that you would find in a building?"

A raccoon would be the most logical answer. Admittedly, the latter guess was a shot in the dark, Cartales said, though it's true that the CAPacabra does share similar dental features and a sloped forehead with a dog.

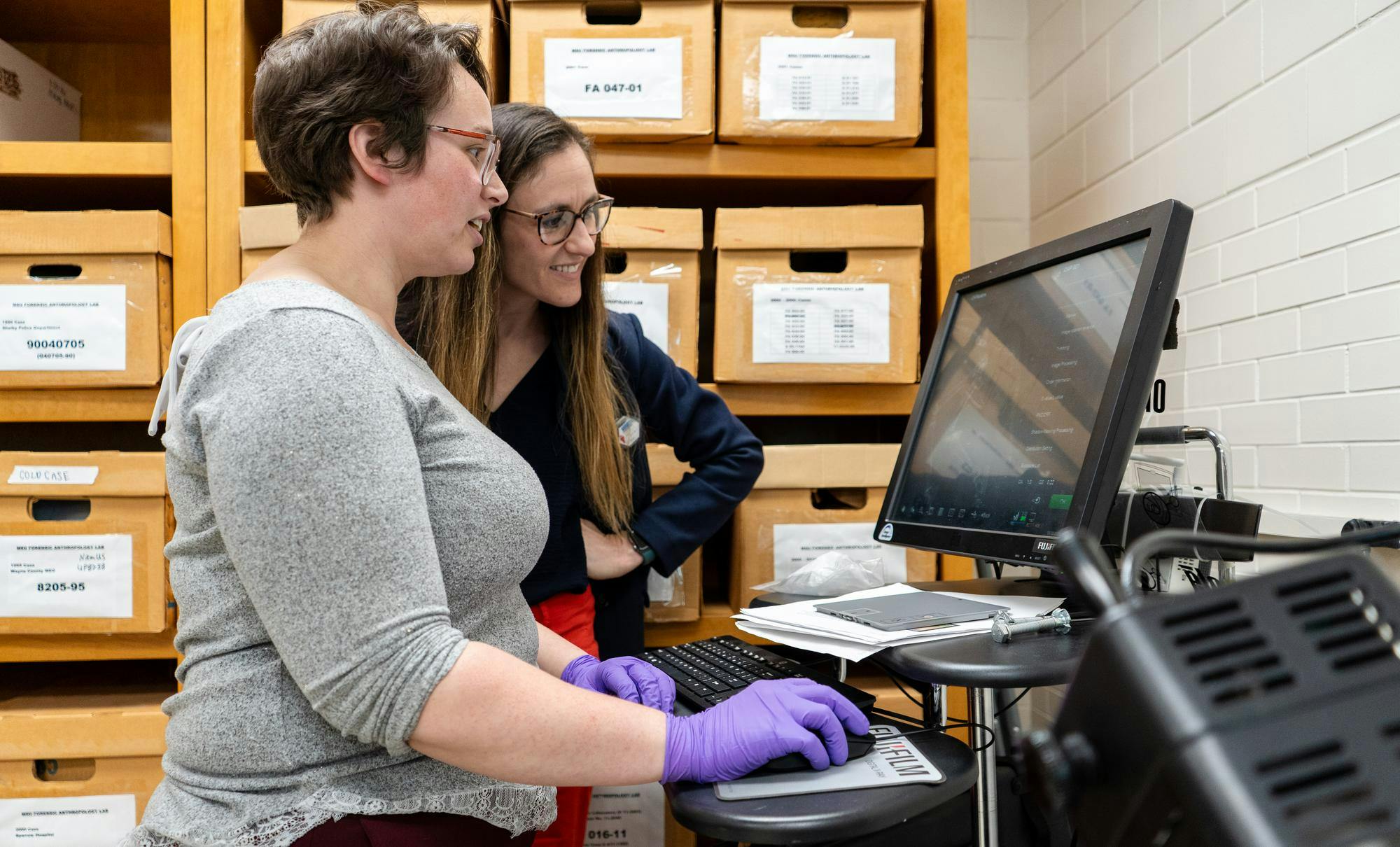

PhD student Jerielle Cartales and Carolyn Isaac, director of the forensic anthropology lab, look at the x-ray of a mummified creature in the forensic anthropology lab in Giltner Hall on April 8, 2025. The creature was found in the roof of Cook Hall during renovations in 2018, researchers are now trying to identify it.

"It's not a dog," Cartales said. "We just need the actual photography proof to show it."

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

She worked to get that proof last week in the Forensic Anthropology Lab, where Cartales and lab director Carolyn Isaac ran the mummies through an X-ray machine.

Cartales gently placed the creature onto black foam placeholders under the machine, stepped back and clicked a button. In seconds, a black and white skeleton appeared on a nearby screen. Cartales gasped.

"I'm obsessed with it," she said.

The creature lie with its limbs splayed out, as if it were mid-pounce.

"It’s kind of like an action shot," Isaac said.

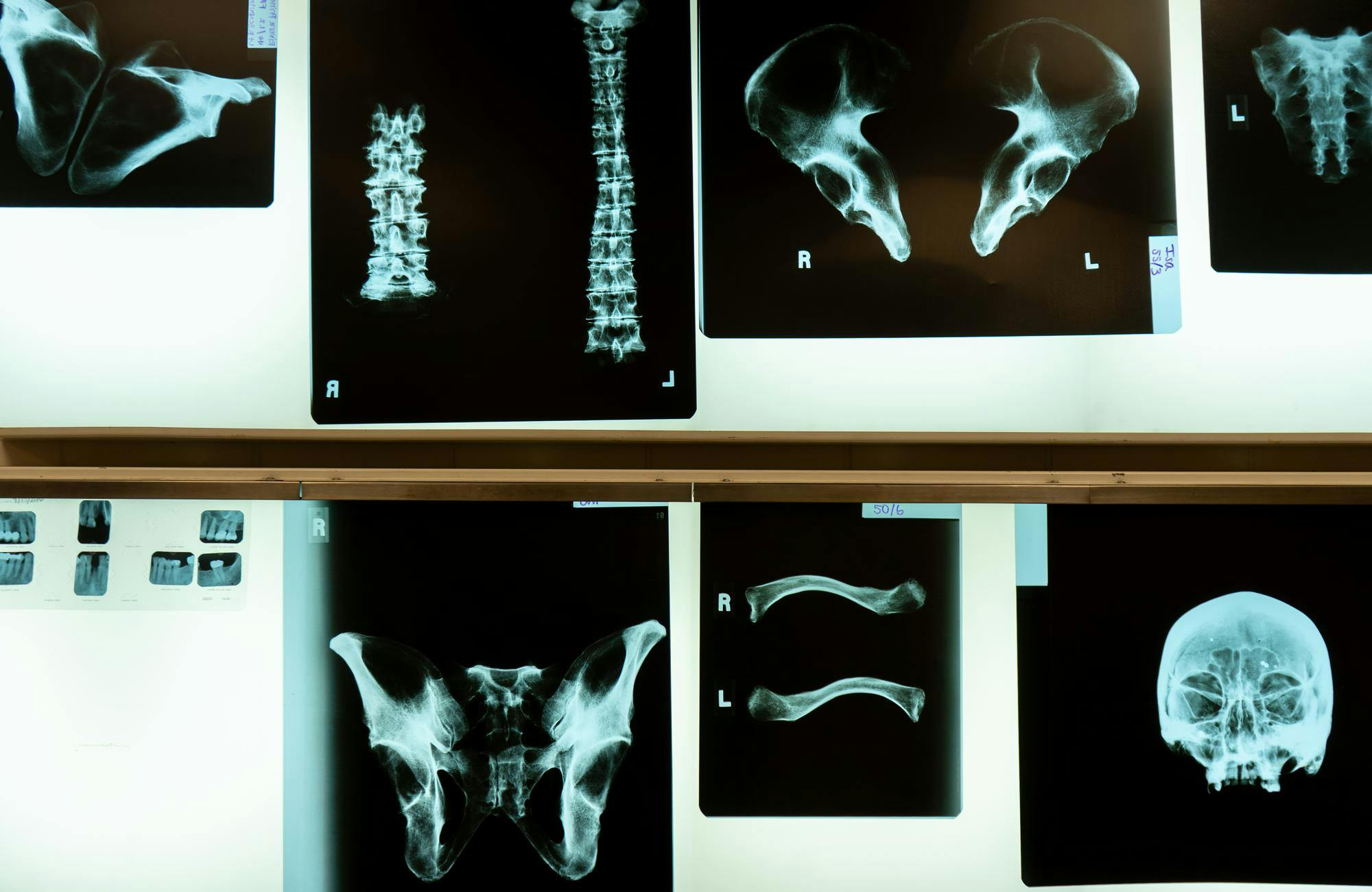

X-rays in the forensic anthropology lab in Giltner Hall on April 8, 2025.

The image appeared to confirm Cartales’ assumption that the creature was relatively young. Some of the CAPacabra’s bones were fused together, while others — like its spine vertebrae — weren’t, Cartales pointed out, meaning it was pretty close to adulthood but not quite there when it died. Bones grow in different pieces, then begin to fuse together as animals reach maturity.

A closer X-ray shot revealed a surprising number of teeth, another indication of its age. It was likely at a point in its life when adult teeth were starting to grow in but its baby teeth were still there, she said.

The CAPacabra’s feet don’t look like dog paws, Cartales said. The best option, she confirmed, was raccoon. Still, she’ll do her due diligence. Cartales plans to compare the X-rays to different animal skulls, which Isaac suggested she get from the MSU Museum.

Cartales won’t have to go far to get a raccoon skull for her comparison. She has one at home.

"As one does," she said.

PhD student Jerielle Cartales points to a spot on the x-ray of a mummified creature in the forensic anthropology lab in Giltner Hall on April 8, 2025. The creature was found in the roof of Cook Hall during renovations in 2018, researchers are now trying to identify it.