Guest essay by Guo Chen, MSU Associate Professor

I am a faculty member of the College of Social Science at MSU. On the night of Monday, Feb. 13, I was among a group of parents signing off an area school district’s educational board meeting on zoom, where the superintendent debriefed the incidents that happened in that school district in the prior week, which involved a lockdown situation.

It was an emotionally charged meeting. Minutes later, I received the MSU alert email notifying a shooter at large. Like many who shared their experiences later, I first treated this message as another email like the ones we received in the past years about thefts and robberies. More information came in, including an unverified list of buildings where gunshots were allegedly heard and students huddled everywhere on campus. I spotted the name of the building where I teach an undergraduate class of 15 students.

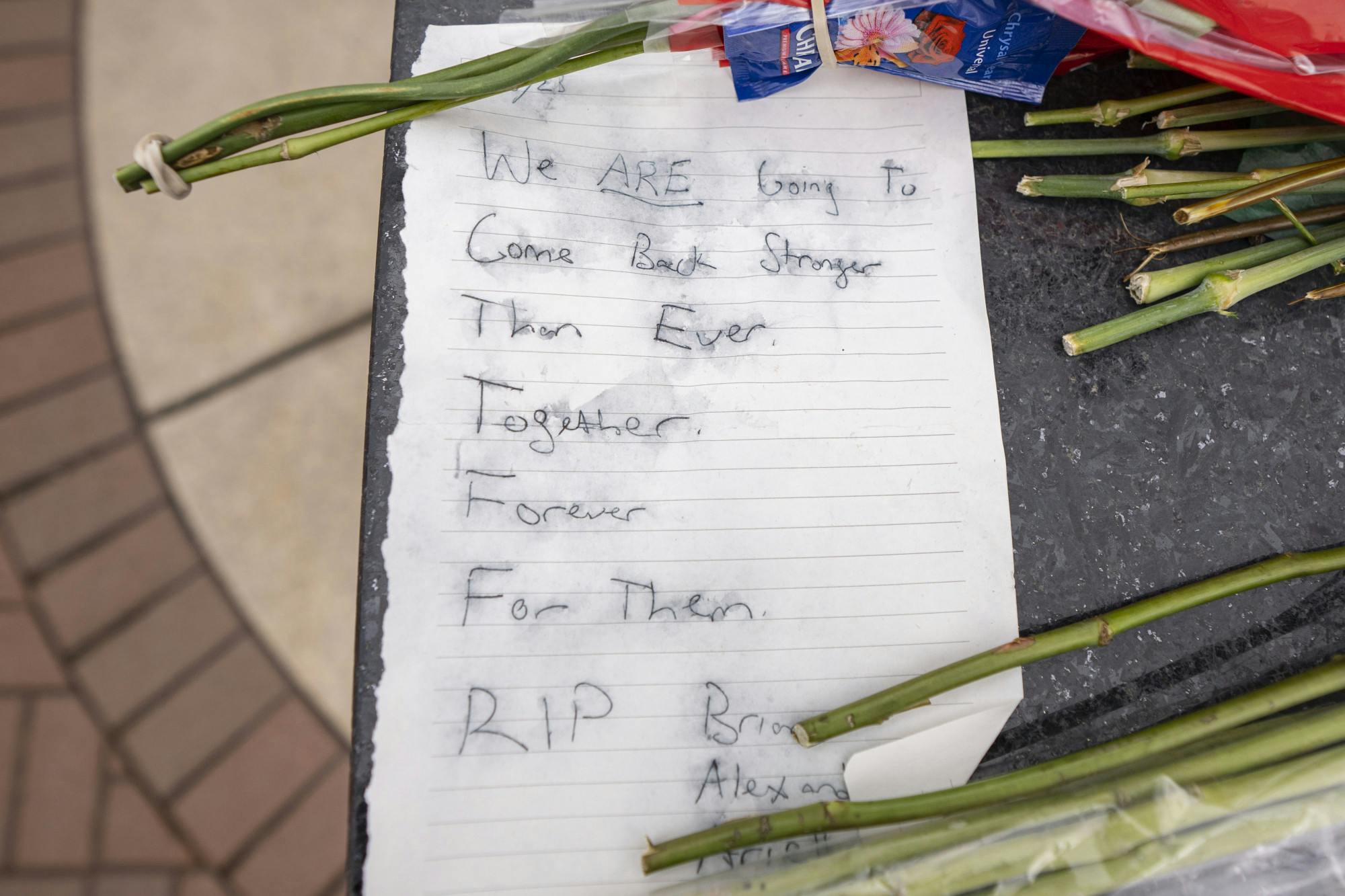

Hours later, all of us were swallowed up by the immense sorrow and pain as more information was shared in waves of press conferences, media reports, email threads and personal stories: the heartbreaking loss of three students, the horrific details about what happened in the two buildings and the five tragically wounded students including international students.

Like many others, I suffered trauma even though I was not on campus, vomited one night after too much sorrow and reading news feeds about the physical injury details, had a nightmare of police entering my house one night, comforted and processed this with my child after she heard what happened, and couldn’t eat or sleep well for days.

As faculty, we received numerous resources and webinar invites through Sunday to learn how to prepare for the first class and how to speak to students when we return the following week.

Berkey Hall is the home of my college. I went in and out of that building numerous times in the 15 years of my time at MSU. Several of my joint program colleagues work in that building. I taught in one of the first-floor classrooms in Berkey for one semester. And my child went to Berkey every Sunday for years to attend a community language school and practiced dragon dance in that hallway of Berkey — they had to relocate.

I also frequented the Union building with my family. I missed a meeting in the Union that Monday afternoon and my child was performing for an Asian community event there weeks before.

Feelings were immediately shared. My colleagues from a university fellow program wrote to each other. One was devastated by losing a student in their program, and one was speechless, given what happened in her beloved department building. My fellow geographers and friends reached out to me from the pacific coast and Hawaii to China. APIDA students from a university committee reached out, and I know many were still processing the trauma from the California shootings.

I am thankful to the students in my two classes who tried to keep each other’s spirits up. On Tuesday, slightly less than half of my undergraduate class returned. Students shared their feelings and what kept them going now: breathing, focusing on cats, spending time with friends and family, reducing news and social media and having meals with friends on campus every day.

Returning to campus for vigils and seeing many reflecting helped with my healing. Still, I am aware the other half of the class has not returned. And, being in class doesn’t mean it’s easy for some. Healing is a long-term process and can be cyclical. Through my last journey of healing from a short-term disability, I know powering through this process can cost more physical and mental drains and may result in a longer recovery process.

I am equally concerned about what messages we want to leave with the immediate and broader community after the incident. None of the university, college, or even department messages in my inbox so far have touched on the many vulnerable members of our community yet.

How much do we know about our international students and many domestic students, who likely had never been exposed to gun culture or violence, who had no family member in proximity to return to, who couldn’t afford the return when this incident happened? I applaud and appreciate the hugging moms, but these students would love to see their families.

How much do we know about the faculty, staff and graduate student members as instructors who didn’t grow up with any training related to lockdowns? A gesture to “hold your hands and walk with you” is not enough to quell their anxiety. They want to see their classrooms and buildings equipped with reasonable security measures, so they can focus on teaching for that one hour and twenty minutes or longer.

How much do we know about our traumatized members in the community, whose “buckets are full” and needed time for “pausing” more than others in the community? They need time to process their sorrows and feelings within their communities, and some may need time to work with professional help to regain their physical and mental strengths.

How much do we know about our student workers, adult students and student parents, who need to work to support themselves, their studies, their families while juggling academic timelines all at once? Are we doing everything we can to support them financially and mentally, especially when some have lost their jobs?

How much do we know about our students, faculty and staff with disabilities, including those with nuerodiversity who might require more support now? How much do we know about the extra burden they must endure each time they seek accommodations?

How much do we know that a message of kindness, allowing time and space with prompt responses to reasonable requests, can have a profound impact on an individual and their family and community?

How much do we know that granting a reasonable amount of pause not only sends a message of care and humanity?

Acknowledging and honoring our vulnerabilities sends a message of strength that empowers everyone including the most vulnerable individuals in our community. It affirms that we as a community are prioritizing our health, are dealing with trauma and will take the time to heal.

I am not a trauma expert, but I am an urban geographer. I teach theories about social justice and the city in my classes. We use Rawls’ famous reasoning device of the “veil of ignorance” to discuss how a group can reach a just decision. If we did not know our social positions in society and thereby had no idea who would benefit the most and the least from any collective decision, what collective decision would we make?

This hypothetical situation lends to the imagination that anyone could be in a disadvantaged position in our society at any time. If we do not step in the shoes of the most vulnerable, our decision will likely be on the opposite side of the greater good.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Discussion

Share and discuss “Guest Essay: Post-trauma, we need empathy, understanding about the most vulnerable community members” on social media.