In 1972, five Michigan State University students and faculty came together to form the Southern Africa Liberation Committee, or SALC. In the ensuing decade, they would persuade the university to become the first in the nation to fully divest from Apartheid South Africa.

Now, at the 50th anniversary, organizers and historians see the legacy of their fight in the fossil-fuels divestment debate that MSU is embroiled in today.

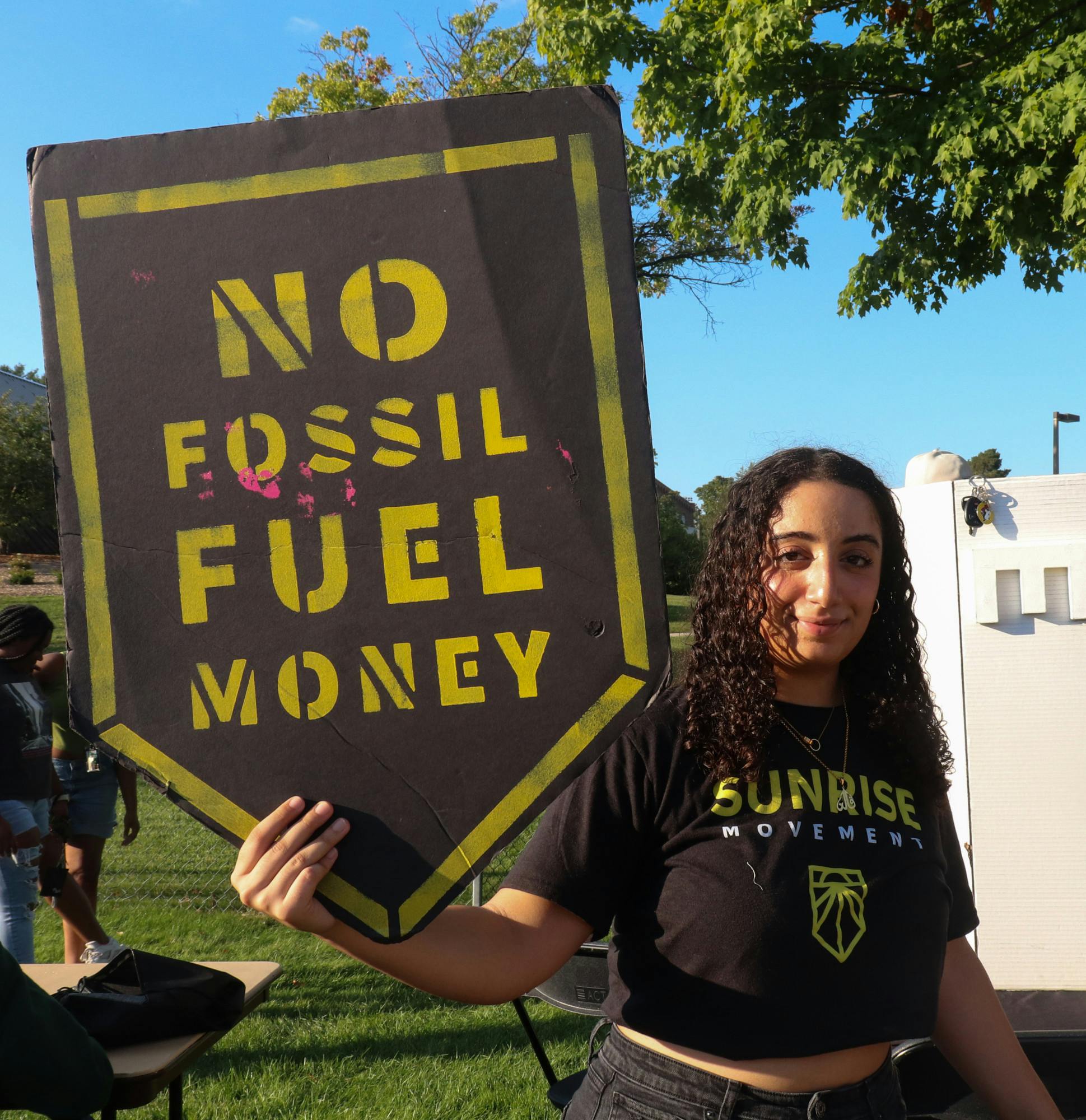

Comparative cultures and politics sophomore Jesse Estrada-White, a leading organizer in Sunrise MSU’s fight for fossil fuels divestments, says that the work of the SALC serves as a major inspiration for MSU divestment activists today.

The South African investments the SALC protested totaled about $68 million in today’s dollars, and included holdings in major Michigan companies like GM, Ford and Kellogg’s. MSU’s decision to pull out of those companies was controversial.

Today, MSU's fossil-fuel investments total about $90 million, and are mostly contractual private investments. This is the primary obstacle for organizers, as the university argues that pulling out of these private investments could lead to breach-of-contract lawsuits, possibly ending in damages larger than the investments themselves.

The timeline is also a consideration. It took six years for organizers to persuade the board to fully divest from South Africa. The fight today only goes back to 2018.

Estrada-White says Sunrise members are inspired by the length of the previous efforts and the idea that persevering people could persuade those in power to make such a large change.

“A lot has changed – politically, economically, socially – since 1978. I think that's obvious,” Estrada-White said. “But, the fact that it's always going to take us on the outside, pushing the board to do what is right, I don't think that’s changed at all.”

Despite its longevity, the SALC’s sustained six-year fight still put MSU at the front of the pack for divestment. Conversely, in the short time since the beginning of today’s efforts, the university has lost its opportunity to be a trendsetter. In 1978, when MSU divested, it was the first university in the U.S. to do so, and it’s credited with inspiring others to do the same in subsequent years.

Today, MSU is behind the trend on fossil-fuel divestment; 20 major universities divested in 2021 alone.

Estrada-White says that early efforts tried to “play on the legacy of what had happened with South Africa, to kind of give the same opportunity” to be ahead of the times.

“Now we're past that point,” Estrada-White said. “They can't really be leaders in this anymore. Universities are divesting left and right.”

Another major difference is simply the amount of attention and support on campus. SALC organizers staged numerous boycotts and sit-ins, they distributed apparel and pins to spread their message and they famously built and occupied a “shanty” along the Red Cedar river to promote their message.

There was also more cooperation between various university groups. Both today’s organizers and the SALC had ASMSU support, but the South Africa campaign also saw major cooperation from the council for graduate students and the faculty senate.

The early organizers themselves were also a broader group. Today, Sunrise is supported by many faculty members and graduate students, but the planning and demonstrations are essentially entirely undergraduates. The SALC had many undergraduates involved but was often led and guided by professors and PHD candidates, who would be around for more than a few years.

David Wiley is a Professor Emeritus at MSU, national president of the African Studies Association and has spent over 60 years researching Africa. On top of researching it, he was on MSU’s campus during the SALC’s campaign. Wiley says a great example of that kind of cooperation is former MSU head tennis coach Frank Beeman.

Beeman, a major supporter of the SALC, was known to lobby MSU presidents and administrators over private tennis lessons during his time as the university’s coach.

In a 2016 panel discussion moderated by Wiley focusing on the SALC, Beeman was asked about how he used his access to aid the SALC.

“There wasn't any pitched discussion, but they knew how I felt,” Beeman said in the panel. “And occasionally, because both of them were tennis players, I would be playing with them and discussing that kind of thing.”

Wiley says that having Ph.D students and faculty involved in organizing creates “continuity,” and makes for stronger long-term efforts.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Estrada-White said Sunrise isn’t too worried about continuity and recruitment is made easy by the fear young people feel for climate change.

“Everyone has a vested interest in the earth surviving, right?” Estrada-White said. “So there's always gonna be someone willing to take on this fight.”

SALC researcher Christopher Root pointed out another difference that could be slowing progress: MSU’s board is currently in tumult over another major issue. She said that in the 70s, the board could focus on issues like South Africa divestment, while today the board is too busy with Title IX concerns and the fallout of the Nassar abuse and cover-up, to give time and attention to issues like fossil-fuel divestment.

“(Title IX) is an enormously important issue that has taken a lot of political energy at MSU,” Root said. “Some of it, doing important political work, and some of it just being a horribly bad administration that’s damaged many, many people and MSU’s national reputation. So, you know, that's been there.”

Despite the board’s current problems, for Estrada-White and his peers in Sunrise, waiting for the investments to expire isn’t an option. The legacy of the SALC shows him it’s possible to make divestment a reality.

“Eventually they're gonna have to divest ... we're gonna keep putting pressure on them until they do,” Estrada-White said. “In many ways, divestment needs to happen now, but we understand, just like they did back then, that it's gonna take time. We're gonna keep pushing, we're determined. This is something that we're very passionate about, and it's not something we're ever going to give up.”

Like organizers today, the students behind the SALC were inspired by those who came before. Root says that many of their childhoods and high-school years coincided with rampant student anti-war organizing, and that in the same way that climate activists today draw on the SALC for inspiration, SALC spartans looked back on anti-war campaigns at MSU for guidance.

“For some folks, the history of anti-war organizing was in the background,” Root said. “That if that happened, it was possible that the anti-apartheid organizing could become a growing political issue, if people addressed it.”

Root now runs the African Activist Archive. She suggests readers visit their website for further information and a vast collection of primary SALC artifacts and documents.

Discussion

Share and discuss “50 years after divestment victory: Can MSU do it again?” on social media.