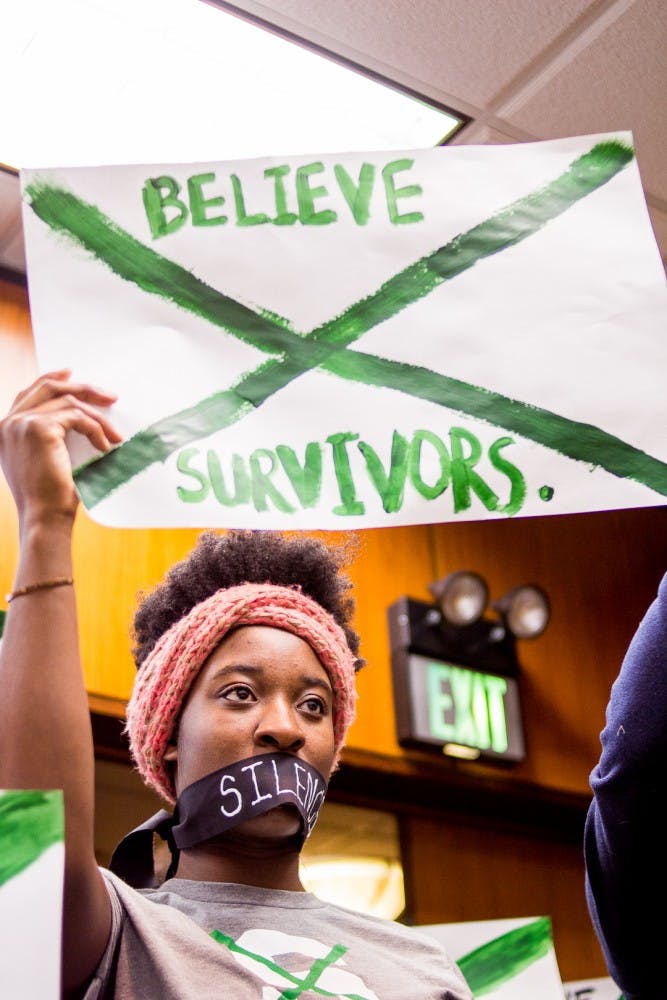

Silence cannot be our answer to sexual assault.

The silence we create is a product of fear and insensitivity — the coach who fails to report, the professor who pulls rank, the family member who ignores the signs someone they love has gone through trauma.

There will always be a monster ready to take up residence in silence, particularly in a culture that would rather place blame on a short skirt than one’s inability to control themselves. We cannot allow this narrative to drown out the voice of survivors.

This focus on silence is not to shame survivors who choose not to report. Reporting isn’t possible for everyone. This falls on us — the peers, the administrators, the politicians and the loved ones of survivors — to do something.

We have to start talking about this issue, and we have to do it right.

These conversations are hard, but important. We need to start the conversation by believing survivors and continuing to show compassion and support during their fights for justice.

In order to turn the tide against a culture that enables sexual assault, we must know how to appropriately speak to survivors. This is evident in the foul ways Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and survivors present at former MSU gymnastics coach Kathie Klages’ trial, were questioned.

We must recognize the double standard in our judgment of recollections from abusers and survivors. If the survivor making an accusation does not remember a detail from one of the most traumatic moments a person can endure, they’re often framed as having less credibility. When Larissa Boyce couldn’t remember one of her coaches’ names as she was questioned during Klages’ trial, Klages’ attorney jumped at the opportunity to question Boyce’s credibility.

If the accused says they do not remember minute details of the day in question, it rarely damages their credibility in the eyes of the public. Think of Brett Kavanaugh, who testified to not knowing if he had ever been blackout drunk or who he was with at high school parties.

Blame is placed on the victim, and the accused’s reputation outweighs the victim’s safety. Victims are questioned when they report — or even just as they talk with their friends — “Do you know what the consequences could be for your abuser?” or “How much did you drink?”

During Ford’s hearing, prosecutor Rachel Mitchell chose a line of detailed questioning about what happened before and after Ford’s assault. Mitchell asked how loud the stereo was, and if and when it was turned off. She asked about a conversation going on a floor below Ford when Ford was in the upstairs bathroom. She showed Ford maps of the neighborhood where the assault occurred 36 years ago — without street names — and asked Ford to mark specific houses she recognized.

During Klages’ trial, survivors faced similar questioning as Ford, despite the fact their assaults were not the subject of the hearing. A hearing to determine if Klages lied in an investigation became about witnesses’ memories.

The burden of proof is on the survivor in the justice system, in the Senate and in the court of public opinion. It’s illogical.

Survivors have many reasons for delaying reporting, being vague or not wanting to talk about their most traumatic moments. However, there is a strong expectation within the justice system for victims to report promptly.

We cannot play games with memory and pass off minute details as vindication while dismissing violent, vivid recollections as hearsay. We cannot continue forcing survivors to publicize their trauma as a condition of their “honesty,” just to invalidate it if their experiences are inconvenient to our political or legal goals.

In order to see the change we want, we first need to change.

We, as Spartans and college students, need to change the way we talk to and about sexual assault survivors. This needs to happen on our campus — regardless of whether public officials listen to survivors who come forward.

If your friend tells you they think they’ve been sexually assaulted, don’t ask “Are you sure?” or “Are you remembering it correctly?”

This is not empowering. Believe survivors.

Don’t question the validity of their stories based on the time and place they decided to tell them. Just because survivors decide to come forward with their stories weeks, months or years after an assault doesn’t mean their accounts are any less credible.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

During the Kavanaugh hearing, Klages’ trial and other cases, the rhetoric surrounding the stories and memories of survivors has been disrespectful and antagonistic.

Everyone processes trauma differently. No survivor should have to abide by a timeline or a deadline to come forward with their experiences.

The State News Editorial Board is made up of the Editor-in-Chief Marie Weidmayer, Managing Editor Riley Murdock, Campus Editor Kaitlyn Kelley, City Editor Maxwell Evans, Features Editor Claire Moore, Sports Editor Michael Duke, Photo Editor Matt Schmucker, Copy Chief Alan Hettinger, Diversity Representative S.F. McGlone and Staff Representative Anna Nichols.

Discussion

Share and discuss “Editorial: Silence is not the response to sexual assault” on social media.