Her quick footsteps echoed through Spartan Stadium as she walked from the elevator to meet for a brief 20 minutes while at work. That’s all the time she had.

Sirrita Darby doesn’t get many spare minutes these days. She works 40 hours a week at MSU Greenline and WKAR on top of two classes and tending to her 1-year-old son, Parris Jr. But last semester was busier yet, with 20 credits, an 18-hour work-week at Microsoft Corp. and Teach for America and “PJ” always on her mind.

Yet she still managed a 3.4 GPA. It was one of her busiest but best terms, now a senior double majoring in social relations and policy and communication, with a specialization in public relations and an economics minor to top it off.

It was her grit and determination that kept her afloat.

“I don’t take on more than I can bear,” Darby said. “I wake up at 5 every morning. I didn’t sleep a lot last semester,” she laughs. “But it was definitely worth it.”

Darby said her mother and grandmother both had children when they were younger, too. They dropped out of high school, but Darby refuses to follow the stereotype.

“What statistic do you want to be a part of?” she asks.

Social realities

A striking number of minority students take longer than four years to graduate — many never do at all, according to a recent study. It seems racial inequalities are embedded even at the university level.

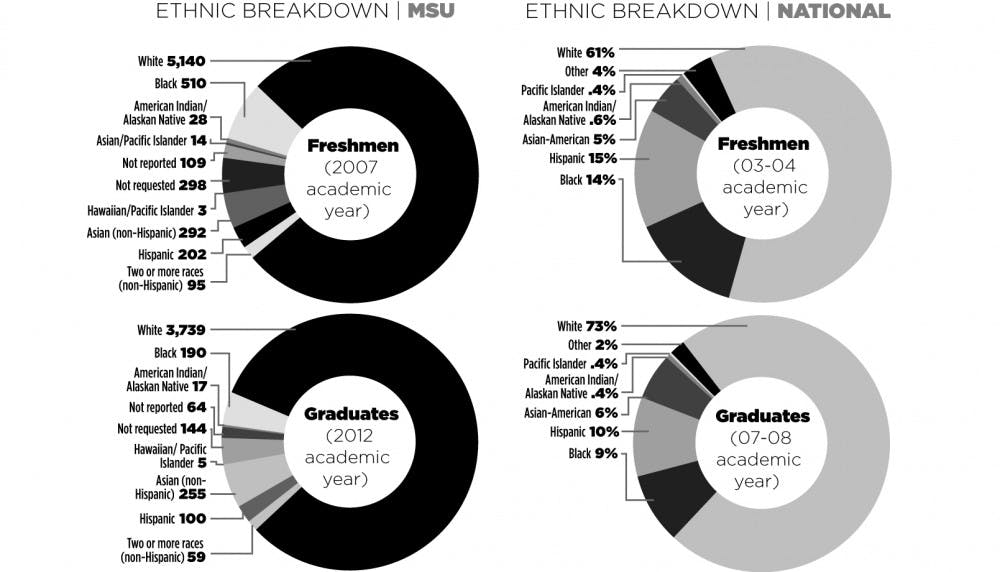

Five hundred and ten new black freshmen enrolled at MSU in 2007, according to data from the Office of Registrar. By 2012, the average five years time it takes many students to graduate, 190 African Americans actually received bachelor’s degrees. That’s about a 37 percent graduation rate, assuming those new baccalaureates came from the same incoming class and finished in the average amount of time.

The estimate could be off, since that’s only a five-year set, but it could also echo a larger trend at work.

A new report from the American Council on Education, or ACE, showed — of all incoming freshmen in the nation — 14 percent were African American in 2003-04, the most recent national data available. But by 2007-08, only 9 percent of the bachelor’s degree recipients were black.

In the same years, 61 percent of incoming freshmen were white. Four years later, 73 percent of the graduates were white, as many of the minority students failed to receive degrees.

It’s a painfully persistent trend that shows no signs of waning. The lead researcher on the ACE study, Mikyung Ryu, said it’s likely to get worse if nothing is done.

“Most likely, the underrepresented are not getting enough financial aid,” Ryu said.

But she added that’s only one part of the problem of “noncompletion,” which an array of factors contribute to — from meager K-12 funding in poor districts to low socioeconomic status, Ryu said.

“It sort of creates the permanent vicious circle. It’s very hard to pinpoint just one piece of the puzzle,” she said.

One step forward, two steps back

Meanwhile, a record number of Hispanic high school students are entering universities and colleges, according to a study from the Pew Research Hispanic Center in Washington, D.C. last month. That’s big progress, considering Latinos have the highest high school dropout rates of any other ethnicity.

But the problem of noncompletion in college, said sociology professor Ruben Martinez, is equally bad for Latino students. Many of those new freshmen might never graduate.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

“First of all, the K-12 system isn’t preparing them to go to college,” Martinez said, who also is the director of the MSU Julian Samora Research Institute that focuses on Latino communities.

Cristian Dona-Reveco, a visiting professor at MSU, agreed, stating many minority students have to work to survive while taking courses. That makes many simply unable to handle the tough workload as well as Darby.

“A day only has 24 hours,” Dona-Reveco said. “You have to sleep at points. So you either work to eat or you study. At the end, you’re not going to study enough, and you’re going to suffer. There’s always something that has to give.”

And while Darby managed to stay afloat in a cruel world, unfortunately, said Dona-Reveco, she’s the exception. Not the rule.

Discussion

Share and discuss “Graduation numbers racially imbalanced” on social media.