The more than decade-old discussion crossed Izzo’s mind again this week, as the traumatic details of an apparent murder-suicide involving Jovan Belcher, a member of the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs, and his girlfriend captured national headlines.

The MSU men’s basketball coach closely monitored the situation from afar, watching the press conferences led by Chiefs head coach Romeo Crennel, learning lessons he hopes he’ll never have to use.

“You see that situation and it’s hard,” Izzo said. “I did want to be involved in it because I think we’ll all go through different situations in our lives, and (Crennel) handled one of the most drastic ones in about as classy, and, I thought, pretty upfront (way).

“We’re all in high-pressure fields. When you’re a college athlete at a place like this, it’s a high-pressure endeavor on their part, so I think (psychologists) are a big part of sports. I think they’re going to be a big part of life pretty soon.”

The issues within the scope of psychological support for athletes aren’t always as extreme as those dealt with in Kansas City this weekend, yet still affect student-athletes on a regular basis.

It’s been 13 years since Saban last served as MSU’s head football coach, and although psychological resources are available to student-athletes, MSU’s athletics department still doesn’t have a full-time professional on its staff to deal with the psychological needs of the athletics department.

Yet as the sporting culture that used to tell children it wasn’t OK to admit weakness continues to evolve, Izzo believes structural changes soon could follow.

“You’re either all in or you’re all out on something like this,” Izzo said. “The need on an athletic staff is going to be there. We have people to use, but I think getting somebody full time is definitely in the very near future at a lot of universities.”

Learning to teach

Izzo had heard of sports psychology, but didn’t begin to take it seriously until 1991, when former Atlanta Braves pitcher and Michigan native John Smoltz sought help from sports psychologist Jack Llewellyn, whom Smoltz credits for helping save his career.

Since then, Izzo said he’s wished he’d been able to complete his minor back when he was in college, but the psychology courses proved too difficult.

Still, he and MSU football head coach Mark Dantonio said it’s a skill they’ve had to use in some capacity nearly every day.

“I‘ll probably be teaching it here before it’s all over,” Dantonio joked at his weekly press conference on Nov. 17. “We talk to our sports psychologist a lot, ask him how to handle different problems (and) get different viewpoints on different things.

“But nobody can really know how that felt on that field except for people who have gone through it on that field or in other areas of life. You feel bad, you understand that you feel bad, but you don’t really know the depth of it until you experience it yourself.”

But for junior quarterback Andrew Maxwell, gaining a new perspective from an outside source, such as Lionel Rosen, who works with MSU athletes, can be beneficial.

“I’ve met with him numerous times, (and) I know a lot of players on our team have met with him,” Maxwell said. “He just brings a different perspective because he’s not in the program every day, and he’s able to look at it from an outside perspective and a more cerebral perspective and put things in a way you’ve never thought about before. … That’s something I’ve benefited from, and I know a lot of guys on our team have also.”

In an email, Rosen, who has been an MSU psychology professor since 1970, said he is unable to speak to the media regarding his work, in order to maintain the trust required in his relationships with members of the athletics department.

New generation, new attitudes

When kinesiology professor Dan Gould began working in sports psychology about 35 years ago, talking about thoughts and feelings was a hidden taboo.

“If you said, ‘I’m working with someone on my mental game,’ you wouldn’t want anyone to know. It meant you had problems,” Gould said. “Now, athletes are more accepting of mental training, like it’s strength training or nutrition. … You don’t have to sell it hard like you used to.”

One of the on-the-field areas Gould said sports psychology can make the biggest difference is for kickers in football, and senior kicker Dan Conroy, who has struggled by missing more field goals this season than he had in his previous three years combined, said it’s a resource he’s used.

“I’ve done it some, I haven’t done it all the time, but … when I find it necessary, I might go and talk to him for a little bit, or even when I’m not struggling, just to pick up a couple pointers here and there,” Conroy said. “In kicking, I think 70 percent of the game is mental, so if you’re mentally right, you should make a lot of field goals.

“I don’t think it’s a weakness at all to be seeing a sports psychologist. If anything, it can give you a benefit that you can’t get from working out and lifting weights or spending extra time kicking a ball.”

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

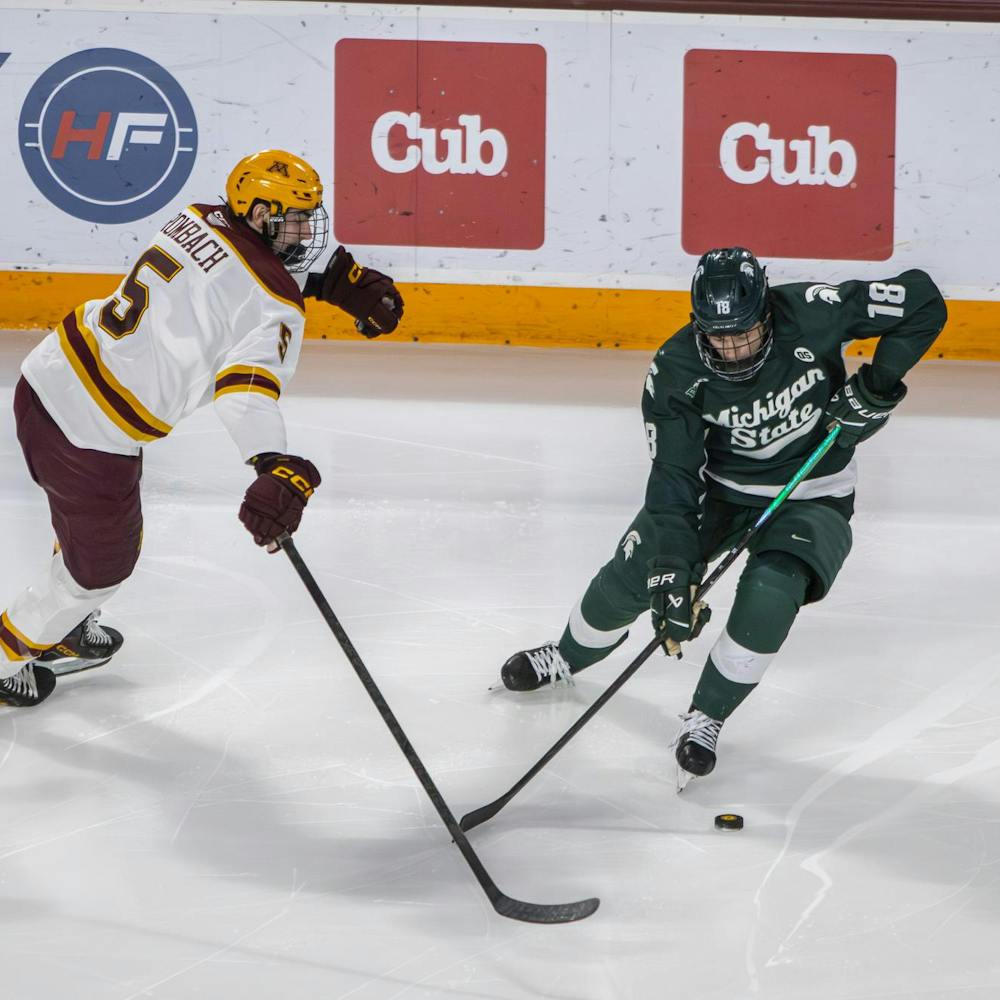

The change in thinking is evident even in athletes such as redshirt freshman hockey defenseman Branden Carney or sophomore men’s basketball guard Russell Byrd, both of whom are recovering from yearlong injuries and haven’t met with Rosen but said they’d be open to anything that could get them playing again.

“It’s always good to talk to somebody,” Byrd said. “You can’t do it alone. That could be a counselor, if you have a relationship with Christ, you can use that because he’ll always be there for you. I haven’t talked to anybody yet but I don’t think it’d be a bad idea because you always need someone to help you get to where you want to go.”

Even coaches aren’t immune, including women’s basketball head coach Suzy Merchant, who said Rosen has helped her and her players deal with issues both on and off the court, describing him as “one of the best resources we have in the country.”

“It’s the loneliest job in the world to be a head coach at a BCS (school) in any sport. It’s tough,” Merchant said. “You’re responsible for everything, which comes with the territory, there’s no question. But it’s nice to have somebody that you can talk to.”

It’s a new willingness to seek help that Byrd said extends beyond East Lansing. He said sports psychology is an option.

“I don’t know if we’ve just gotten different genetically, the world is different now or times have changed, but I think whatever you have to do to be successful, you’ve got to do,” Byrd said. “You’ve got to explore every option.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “Mind Games” on social media.