At a recent Michigan State University Board of Trustees meeting, the institution’s overseers promptly approved a peculiar agreement.

Associate professor of biochemistry Erik Martinez-Hackert would receive tens of thousands in federal grant funding to serve as the "principal investigator" on a research collaboration between the university and the for-profit, biomedical company he owns, Advertent Therapeutics.

That means he was working in his MSU capacity, in a university lab, to develop a biomedical technology his private company could one day profit from.

It was far from the only time that Martinez-Hackert had requested approval for an agreement between his employer and his private company. He’s sought the board’s blessing on seven since 2016, which is required by law and university policy to approve such arrangements.

The board approved every one.

That’s not odd. In the last 10 years, the board has signed off on every single conflict of interest agreement presented to it.

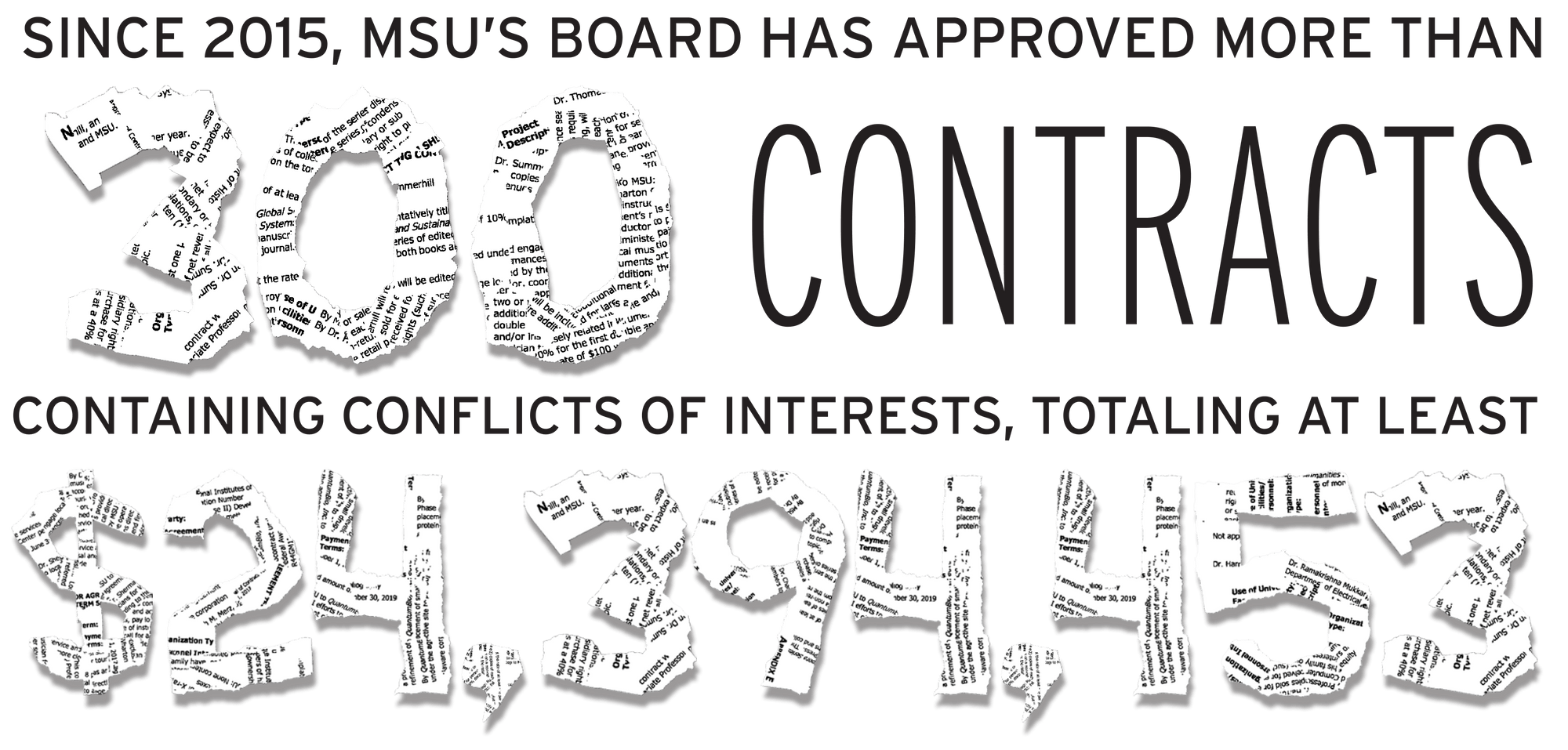

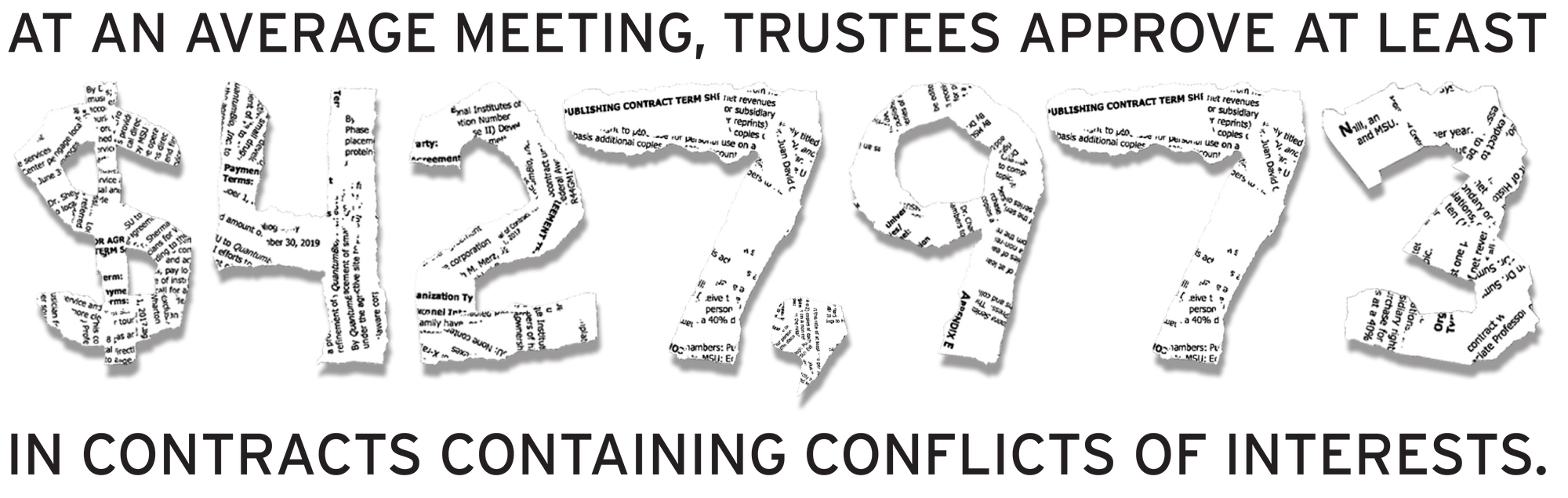

Across over 300 agreements, the board has approved at least $24 million in contracts between the university and private entities tied to employees, according to a State News analysis. Every time, the deals were approved by a unanimous vote with no discussion.

The board chair and an involved administrator defended the process, saying the entanglements with employee-owned companies are mutually beneficial and adequately supervised.

But others are skeptical.

Experts on conflicts of interest said oversight of such agreements is crucial, given that in public-private partnerships between universities and private companies, the latter often gets the sweeter end of the deal.

A junior MSU trustee said he wants to learn more about the university’s process to make sure it's safeguarding against that dynamic. A former board firebrand, though, said the ambitious newcomer won’t get far.

Nature of conflicts vary

Some of the agreements voted on by the board are simple transactions.

In certain cases, they might assert that a conflict is justified because there isn't another way to do the deal, or even that MSU is getting some sort of discount thanks to the relationships at play.

In 2015, for example, the university was looking to purchase a special type of English Horn. Documents presented to the board say there were only two suppliers in the world: One was in Germany, and the other was a local firm owned by a professor in the College of Music. The professor ultimately agreed to sell MSU a horn for $8,800, a 20% discount from the listed price. The board approved the deal, despite the ostensive conflict of interests.

Some deals, however, don’t boast similar benefits, like when the board approved an employee’s request that his wife’s editing company be paid $2,260 to edit a handbook he was working on; or, when a film professor got MSU to pay his son over $6,000 to draw storyboards for "key scenes" in a movie he was working on; or, when an MSU farm manager once spent almost $20,000 in university funds to buy bales of straw from his brother. None of those contracts mentioned a discount for the university, or explained the necessity of contracting a family member.

Those rather straightforward arrangements represent a small portion of the deals that come before the board. The majority are far more complicated, often governing complex, scientific research projects where work and rewards are split between the university and private entities.

Some such agreements see money flow through MSU and then to a private company.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Martinez-Hackert’s deal is an example: A copy of his "conflict management plan" obtained by The State News though a public records request shows he applied for a federal grant through the Small Business Innovation Research initiative, which intends to help startups develop new technologies and "chart a path toward commercialization," and was established under the Reagan administration. With that sort of grant, universities are often brought into the fold as subcontractors, as was the case with MSU and Advertent Biotherapeutics.

Specifically, MSU was given $32,241 by the National Institutes of Health to provide the services to Advertent of producing, purifying and testing a novel protein that aims to prevent muscle degeneration. Bringing to market "therapies" that do just that is the goal of Martinez-Hackert’s company, according to its webpage.

The “principal investigator” tasked with performing that work at MSU? Martinez-Hackert, the conflict management plan shows. So, he was developing a protein as part of his work at MSU, then the "contract research organization" Myologica would test it on animals, and then Advertent would analyze the data from those tests to measure its efficacy. The conflict management plan stipulates that Hackert, in his capacity as Advertent's "Chief Science Officer," would not be involved in analyzing that data, but would receive "reports summarizing the results."

It wasn’t the only time money flowed from MSU to an employee’s organization.

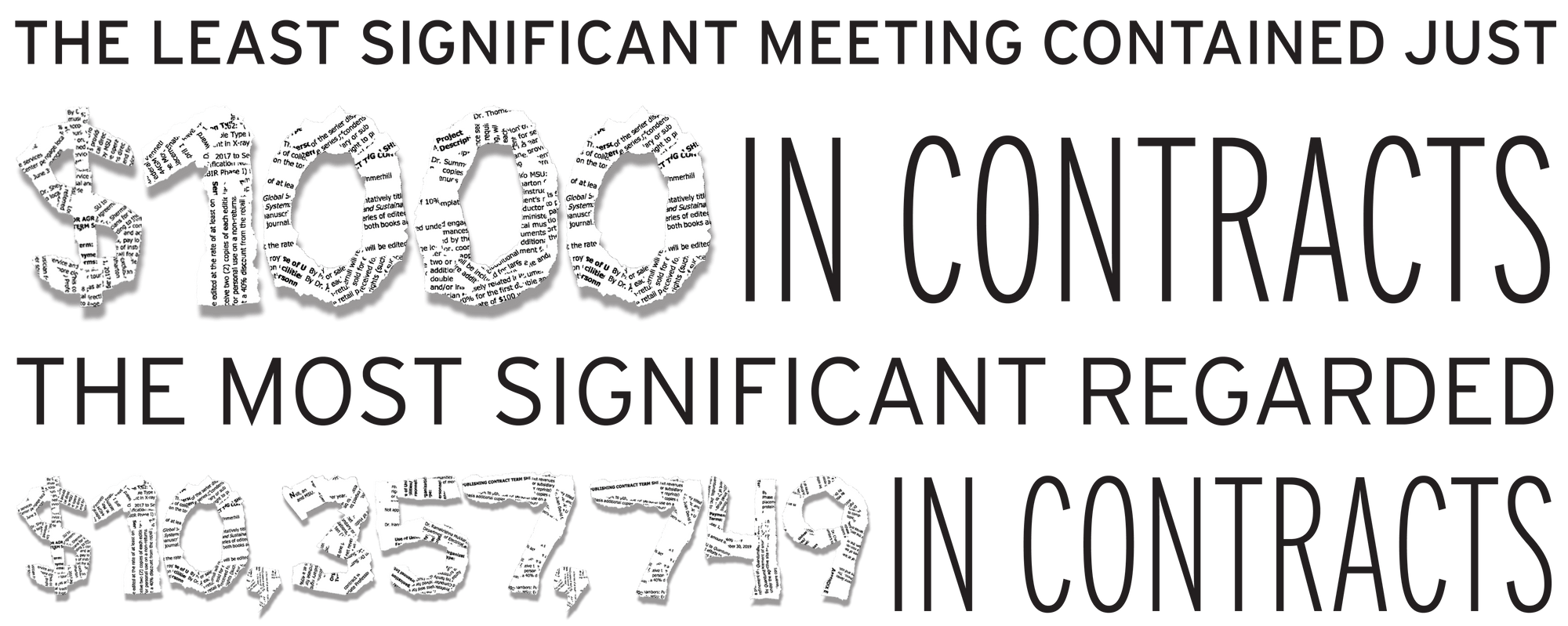

In fact, the most expensive agreement that the board has approved in the last 10 years was one such arrangement. In June 2022, MSU sub-awarded more than $10 million of a U.S. Department of Commerce grant intended to expand internet access across Michigan to Merit Network, Inc, a non-profit, according to the board resolution approving the agreement. When that deal was struck, MSU’s then-executive vice president for administration, Melissa Woo, was also the chair of Merit Network’s board of directors.

Agreements like these, where money flows through MSU to an employee’s organization, are relatively rare. What’s far more common are deals where money flows the other direction — from faculty members’ private companies to MSU, typically for fee-for-service work. As compensation, MSU will either get cash, or an equity stake in the company.

Sometimes these arrangements involve an employee essentially paying the university to let them do work for their company in university labs or with MSU colleagues. Other times, an employee's company will pay MSU for someone else at the university to do work for the company.

Both arrangements have been used by the diamond and crystal companies owned by electrical and computer engineering professor Timothy Grotjohn, who has had 16 conflict of interest disclosures approved by the board over the last 10 years, the most for any one individual. (Grotjohn did not respond to emails from The State News.)

In 2019, for example, Grotjohn wore both hats: His company subcontracted $80,000 of a U.S. Navy award to the university for assistance, and then Grotjohn and a colleague carried out that work in their capacity as university employees, according to contracts presented to the board.

A 2020 arrangement employed the other structure. Grotjohn's company — Great Lakes Crystal Technologies — paid MSU to "develop a preliminary design" for new semiconductor technology. Board documents stipulated that he would be kept out of that work, and a different faculty member in his department would do it.

Experts warn of consequences

Experts on conflicts of interest have broad concerns about the implications of public-private partnerships in university research.

"There’s a lot of money to be made in trying to save lives, and there’s a lot of harm that can happen when you have a financial interest," said Laura Schmidt, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who studies research conflicts of interest.

Financially interested parties can point to universities’ involvement in public-private research partnerships as suggesting a level of legitimacy and neutrality. But in Schmidt’s view, that can obfuscate the truth: Companies’ end goal in these agreements is to turn a profit from their discoveries.

Lisa Bero, a researcher of research ethics at the University of Colorado and an MSU alumnus, argued that in public-private partnerships, private companies often stand to gain more than universities. That’s because while companies get the advantage of being able to claim an "impartial, academic source" ran services for them, or conducted research, the universities’ only real gain is the revenue generated.

While that may be a permissible arrangement in some cases, she said it’s important to ensure fee-for-service work doesn’t "detract from the universities’ functioning in any other way." Bero, who has worked on conflict review committees, said she’s seen such examples. She pointed to a case where a postdoctoral student conducting research was removed from a university lab so that a company could put a different postdoctoral student in the lab to perform testing on its behalf.

In other public-private partnerships, Bero has seen private companies' interests take higher priority than the university’s academic ones in more explicit ways. She explained that when university researchers are contracted to perform testing for companies, they often have to sign confidentiality agreements, which can inhibit them from publishing research findings that overlap with the testing’s subject matter. "That then gets into the whole issue of academic freedom and inhibiting somebody's career."

Given these potential issues, experts said, robust conflict management plans and policies are a must for universities. But Bero said that in her experience, oversight sometimes lacks vigor.

The National Institutes of Health’s guidelines are “still quite lenient,” Bero said. Specifically, she pointed to the NIH’s allowance of investigators having outside financial interests as well as the vague provision that there must be "adequate separation" between their activities funded by NIH and their commercial interests.

To be sure, the prevalence of conflict of interest disclosures in MSU research holds with a broader trend across academia. ProPublica reported that from 2012 through 2019, health researchers receiving federal grant funding reported more than 8,000 "significant" financial conflicts of interest, worth $188 million.

But experts said that universities are just one part of the equation when it comes to ensuring conflicts of interest don’t unduly influence research. Academic journals that publish findings should disclose any potential conflicts, though researchers often “fudge” such requirements, Schmidt said. (An editor-in-chief of the leading journal Cancer Today resigned in 2018 after the New York Times and ProPublica reported he failed to disclose financial conflicts in several articles published in medical journals).

Martinez-Hackert, by his own admission, for example, has flubbed disclosing to journals his ties to companies whose commercial interests overlap with the research’s subject matter. He maintains those were mistakes.

"Because these projects spanned extended periods and my involvement was relatively minor, I unfortunately failed to update my disclosures at the time of publication," said Martinez-Hackert, who also maintained that he contributed to the papers before his company was founded. "Typically, senior or first authors handle disclosure requests during manuscript preparation, and in these instances, they did not request this information from me. As a consequence, these disclosures slipped my attention. Nevertheless, I should have communicated my disclosures regardless."

MSU sees benefit

Martinez-Hackert broadly argues the benefit of his involvement in public-private partnerships between MSU, his employer, and Advertent, his company. He said the "robust" oversight of MSU paired with his personal ethics prevent his competing interests from compromising the work, and that such collaborations "bridge the gap between academic discovery and real-world impact."

He's not the only one to offer a competing argument suggesting that these agreements benefit the university. Conflicts are inevitable, and the review process ensures that the university is usually getting a good deal, said Tom Voice, a longtime professor and administrator in the College of Engineering who serves on the faculty committee that reviews agreements containing conflicts.

In Voice's view, the benefits are there no matter which way the money flows. If MSU is paying a company for something, or sub-awarding a grant, it’s usually because that company has something MSU needs or can do something the university can’t, he said. If a company is paying MSU to do something, he said that generates revenue the university can use for other things.

Voice also espoused a greater societal benefit to MSU’s financial involvement with these companies, describing the deals as a way to make the work of university researchers materially beneficial to people. If a drug is developed in an MSU lab, for example, a private company needs to bring it into the marketplace so people can use it, Voice argued.

"When we have new technologies, we can get them into the marketplace," he said. "If they just end up in journals, we don’t consider that part of our mission, just to have stuff in journals. We consider it part of the MSU mission to benefit the public good."

Issues could arise from the relationships between the university and private companies, Voice said. But, he insisted that the review process at MSU mitigates that risk. Issues are handled through "conflict management plans," which establish firewalls and guardrails for employees working around conflicts.

Most conflicts are first resolved without going through the formal process, Voice said. Faculty can talk to their department chairs and deans and handle things within their college.

Sometimes, though, faculty do fill out forms to escalate the issue to the university’s Conflict Disclosures and Management staff in the Office of Research Regulatory Support. Administrators in that office handle most agreements.

The rest are then elevated to the faculty committee Voice sits on, and was long the chair of. He said they come from a diverse set of disciplines in various colleges, and often bring in subject-matter experts to help them best understand the complex research agreements.

The university’s board then reviews some of those arrangements, as state laws require only that they examine agreements where an MSU employee holds a financial interest in a company doing business with the university.

Board members disagree

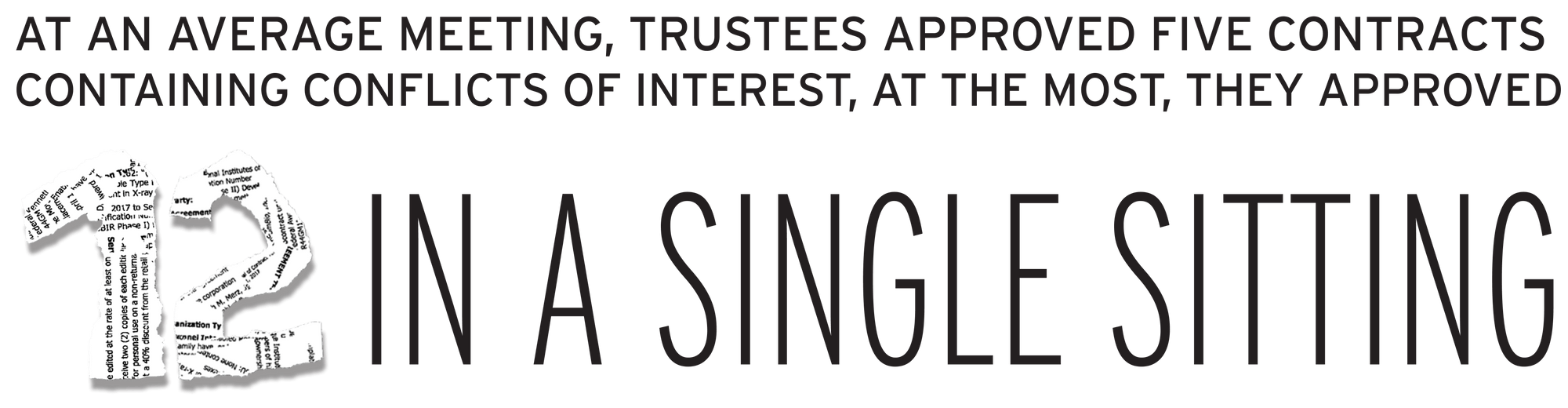

Trustee Mike Balow said that since he joined the board in January, members have never challenged any of the conflict disclosures that administrators present for approval.

Balow said trustees' relative disinterest on the matter is borne out of a trust in the robustness of the process before it crosses to their desk. However, though he hasn’t "been given any reason to get aggressive on it," Balow said he "wouldn’t rule it out one day."

That may become necessary, he said, if he suspects companies are getting more out of a public-private partnership than MSU.

"It’s nice when private companies want to pay MSU to do research — my argument there is it has to be market transaction, it has to be fair," Balow said. "The private company shouldn’t take advantage of MSU to be like 'well, I shouldn’t have to invest in my own laboratories because I’ll just use MSU’s for super cheap.'"

"MSU should say, ‘no, no, we’re going to charge you a fair market price because our lab’s time, and our worker’s time is valuable.’"

Former Trustee Pat O’Keefe said he once tried to make the board more closely involved in oversight of the conflict agreements, but faced pushback from the administration and faculty.

The board is an elected group of professionals hailing mainly from business and law. They don’t have backgrounds in scientific research, let alone the highly technical matters at hand in many of the agreements. Without subject matter experts like those available to the faculty committee, O’Keefe said the board was often out of its depth and unable to truly evaluate the arrangements.

He also questioned what exactly each researcher’s financial interests were in the involved companies. The agreements presented to the board only say if an employee’s ownership in a company is "greater than 1%."

"It would say, ‘they have a financial interest,’ but I need to know more," O’Keefe said. "What is stock that’s more than 1%? Is it just 1%, or is it 99%?"

When he raised questions about the deals in meetings of the board’s Audit, Risk, and Compliance committee, O’Keefe said administrators didn’t know the answers or declined to provide them.

Like the rest of the board, O’Keefe never once voted against approving a conflict agreement. Asked why he never objected, given his concerns, O’Keefe said doing so would have isolated him from the other trustees.

In O’Keefe’s view, the rubber-stamp approval of conflicts was part of a broader pattern, with faculty and administrators saying the board was overstepping when it sought to provide what he deems necessary oversight. He made a similar argument amid his dramatic resignation from the board in 2022.

"The administration never wanted to be questioned by the board," O’Keefe said. "You say that, and now the faculty senate is down your throat."

Asked about Balow’s efforts, O’Keefe said he’s supportive, but worries how long the new trustee’s hawkishness will last. The more questions O’Keefe asked, the more he felt unwelcome among the board and administration, he said.

"He’s gonna find out, like I did, what a lonely place that is in the boardroom," O’Keefe said.

In a statement, board chair Kelly Tebay defended the board’s current handling of the agreements, saying trustees "take seriously our role in this process and are committed to vigorous and appropriate oversight."

After the board approved Martinez-Hackert’s most recent agreement at its February meeting, The State News asked Tebay why the board chose to allow the deal, which included the professor working at MSU on a technology his private company could one day profit from.

She said she wasn't familiar with the deal, which she voted to approve just an hour before. A board committee examined it, she suggested, adding that she’s "not sure what conversations they had."

Photo illustrations by Addison Ogburn.

For a database of all the contracts referenced in this story, click here.