Early in fall semester, three individuals drove to the top of a parking garage on the edge of Michigan State University’s campus, climbed onto its roof, and started smoking marijuana.

It’s far from a rare occurrence on a college campus. Only this time, an unexpected element tainted their youthful indiscretions: The individuals were being watched.

MSU’s 24/7 surveillance system, which integrates thousands of cameras and sensors from across campus, caught them climbing onto the roof. One of its full-time employees reported it to the campus police department. Two officers were sent to the scene, according to police files obtained by The State News via a public record request.

MSU touted the case as a good example of how the university is using its $10 million Security Operations Center, or SOC. Experts in surveillance technology, however, say the situation — which ended in disciplinary findings against the involved officer — illustrates the dangers of such technology.

It’s one of very few examples of the SOC’s use that have materialized since it was first turned on in May 2023. While the system is supposedly capable of assisting campus police in finding suspects of reported crimes, it hasn’t been effective in every case.

In perhaps its most high-profile test, the system was somewhat involved in the apprehension of local youths who beat a gay couple in the MSU library last spring. But in another highly publicized case, officers failed to find the perpetrator of a brazen sexual assault in the MSU Union, even with the help of the system’s many cameras and vast data collection.

Evidence is yet to emerge showing that the system can actually prevent crime, experts say. And, a proposed expansion of the system into East Lansing has also been taken off the table, police officials said.

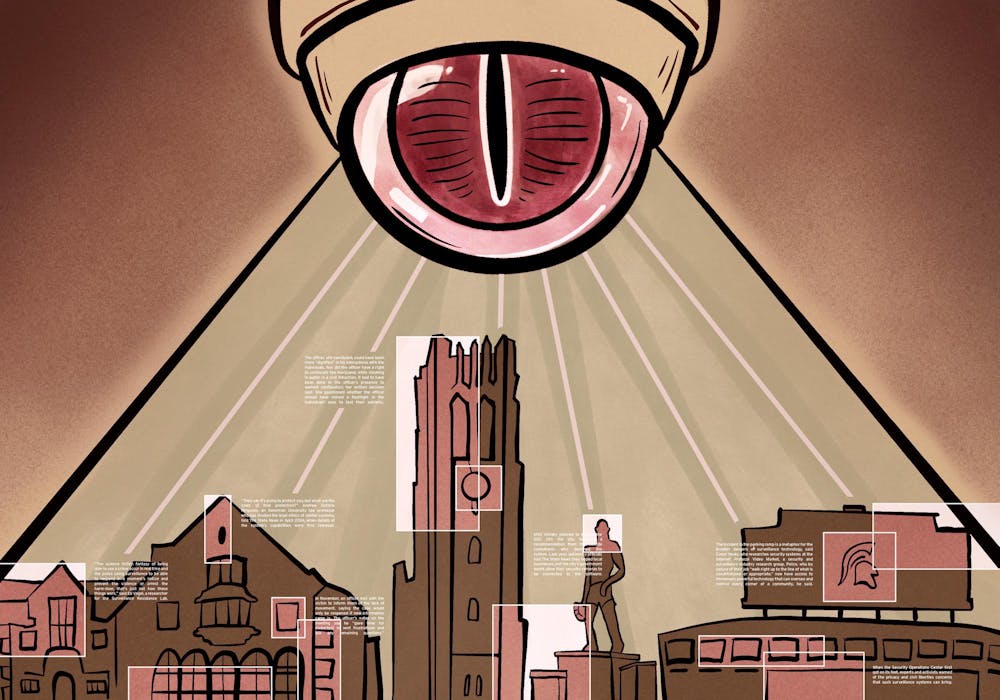

The mixed results further complicate the tense introduction of the pricey project. University officials have pushed to portray the system as a necessary technology that can help students feel safe, especially after the campus shooting in 2023. But activists and experts question the benefits, and argue they are greatly outweighed by risks to civil liberties and personal privacy.

A tense encounter

Up on the parking ramp, an officer approached the individuals and asked for their IDs.

"Which one of you is up here smoking weed?" the officer asked, according to a transcript of footage from their body-worn camera.

"None of us," one replied.

"I smell it, right here," the officer said. "Somebody was. Don’t lie to me or I’ll give everybody a ticket. Right now, we're at verbal warnings. So, be honest. Who is smoking weed?"

Another individual piped up.

"I’m 21," she said. "It’s me."

On the officer’s request, she took a tray from the backseat of the car containing a blunt, a joint and "possibly some rolling papers," according to police records.

An officer took her ID.

"When you run her, let's see if she has anything in her background, cause if she do, she's gonna get a ticket tonight," one officer said to the other.

An officer shined a flashlight into the eyes of two of the individuals, observing signs of marijuana use.

The officer let them leave, but said that if police see them driving out of the ramp in their vehicles on camera, the officer will "come after them for driving under the influence," according to the police records.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

One of the individuals asked if she could put the marijuana tray back in the car.

"No, all of that's confiscated," the officer said. "This is what you get for smoking and not getting arrested or ticketed."

Some time after the incident, one of the individuals called the police department to make a formal complaint against the officers. She felt it was inappropriate that the officer confiscated the marijuana, given that two of the three individuals were legally able to possess it, according to the records.

The department’s internal affairs investigator reviewed body camera footage of the incident.

The officer, she concluded, could have been more "dignified" in his interactions with the individuals. Nor did the officer have a right to confiscate the marijuana; while smoking in public is a civil infraction, it had to have been done in the officer’s presence to warrant confiscation, her written decision said. She questioned whether the officer should have shined a flashlight in the individuals’ eyes to test their sobriety.

When the SOC first got on its feet, experts and activists warned of the privacy and civil liberties concerns that such surveillance systems can bring.

"They say it’s going to protect you, but what are the costs of that protection?" Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, an American University law professor who has studied the legal ethics of similar systems, told The State News in April 2024, when details of the system’s capabilities were first released.

"What’s it like to live on a college campus where police are watching you and keeping track of your youthful indiscretions?" Ferguson said. "I’m quite thankful we didn’t have those camera systems when I was in college."

The incident in the parking ramp is a metaphor for the broader dangers of surveillance technology, said Conor Healy, who researches security systems at the Internet Protocol Video Market, a security and surveillance industry research group. Police, who by nature of their job "walk right up to the line of what is constitutional or appropriate," now have access to immensely powerful technology that can oversee and control every corner of a community, he said.

To John Prush, who directs MSU’s Public Safety Operations, the incident was a "great example" of how the Security Operation Center keeps campus safe.

"If you're sitting on the roof of the ramp, that's an absolute safety concern," he said.

It’s unclear how much of the SOC's workload consists of minor incidents like the one on the parking ramp. In fact, it's unclear what exactly the SOC has been used for at all.

Asked for examples of recent cases in which the SOC had played a significant role, Prush said he was "hesitant" to give any. The department can’t discuss open cases, he said, and he wasn’t sure what was still open or closed. Neither Prush nor a department spokesperson could recall any closed cases.

Prush declined to give hypothetical examples to illustrate how the system might be used, saying, "My imagination is the same as yours."

The SOC did come in handy when responding to a report that someone fell in the Red Cedar River, department spokesperson Nadia Vizueta said.

Police were able to quickly access camera footage that showed the individual enter the river then exit shortly after. Without the integrated system, it would have taken longer to locate the camera feed, Prush said.

The system is also being used to detect when building doors are propped open, Prush said, allowing police to respond.

Tracking suspects

While university officials have said the system will broadly make campus safer, experts suggested its capabilities are more limited.

"The science fiction fantasy of being able to see a crime occur in real time and the police using surveillance to be able to respond in a moment's notice and prevent the violence or arrest the harm-doer, that's just not how these things work," said Ed Vogel, a researcher for the Lucy Parsons Lab, which studies surveillance and policing.

If there’s anything the system could be good at, it’s tracking down suspects of reported crimes, experts said. But, the results of even that narrow test are mixed thus far, according to police reports reviewed by The State News.

After a group of local youths viciously beat a gay couple in MSU’s main library, parts of the SOC were employed as police tried to apprehend suspects, though it’s unclear how essential the system was to the eventual arrests.

Officers put together descriptions of the suspects by talking to the victims and witnesses, some of whom had taken photos and videos of the event on their cellphones.

Using that information, officers did find SOC footage of the suspects on a nearby parking structure. They also used facial recognition in an attempt to identify the suspects, employing software from Clearview AI, a firm that is controversial among civil liberties advocates and has paid hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements to people who sued over privacy concerns.

But, the eventual arrests made in the case drew largely on interviews with witnesses and suspects, as well as a key identification made by a suspect’s high school principal.

In another high-profile case, the SOC was wholly unable to help police make an arrest.

On a Thursday evening last September, someone reported a sexual assault at the MSU Union. They didn’t know the perpetrator, but were able to describe him to officers, according to a police report. Within hours, they used the SOC to find footage of the interaction, but couldn’t tell where he fled to. Officers drove around looking for the suspect, but couldn’t find him.

They later reviewed more footage from the SOC, but still couldn’t establish a clear trail. Just after the alleged assault, the suspect crossed Grand River, moving off of MSU’s campus and into the City of East Lansing. With that, he escaped the view of the SOC.

MSU initially planned to expand the SOC into the city, following a recommendation from the outside consultants who gave feedback on the system. Last year, university officials told The State News they hoped local businesses and the city’s government would allow their security cameras to be connected to the software.

But, in the interview last week, Prush said they are no longer planning to pursue the expansion.

After the unsuccessful attempts to use SOC footage in the Union sexual assault case, officers publicized images of the suspect online and in the media. Campus police also briefed officers on the case ahead of big events like home football games, hoping to spot the suspect out and about, according to the police report.

Numerous tips came in, and officers followed some leads, but an arrest was never made.

In November, an officer met with the victim to inform them of the lack of movement, saying the case would only be reopened if new information came in. The officer’s notes on the meeting say he "gave time for (redacted) to vent frustrations and ask any remaining questions."

A spokesperson told The State News that the case remains open.