Military recruiters often make a simple pitch: enlist, serve, then college is free.

It's a well worn deal. First established in 1944 under the G.I. Bill, Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court have repeatedly expanded the benefit as nearly 1 million veterans and dependents have used the funds, sending billions in revenue to colleges.

But at Michigan State University, the exchange isn’t so simple. University-employed middlemen stand between students and the federal funds they’re entitled to.

A shortage of them has led to persistent delays. MSU lags far behind federal recommendations, with just two employees tasked with certifying payments for more than a thousand students.

In meetings with administrators, responses to surveys, and interviews with The State News, students who rely on the G.I. Bill complain of a consistent problem: Every semester, the bottleneck delays their funds for months. To cover their expenses in the interim, they’re getting extra jobs, taking on debt, or simply forgoing certain expenses.

The issue has spurred years of activism, but advocates fear their pleas are falling on deaf ears. They say MSU’s president, board and top administrators have heard their demands, but taken no action.

The university claims that the issue is being examined. Still, students are skeptical.

"The money is out there, the laws are there, it’s just a lack of action from the administration," said Andrew Branam-Drock, who’s studying international relations at MSU after serving for eight years in the Army.

‘Salt in the wound’

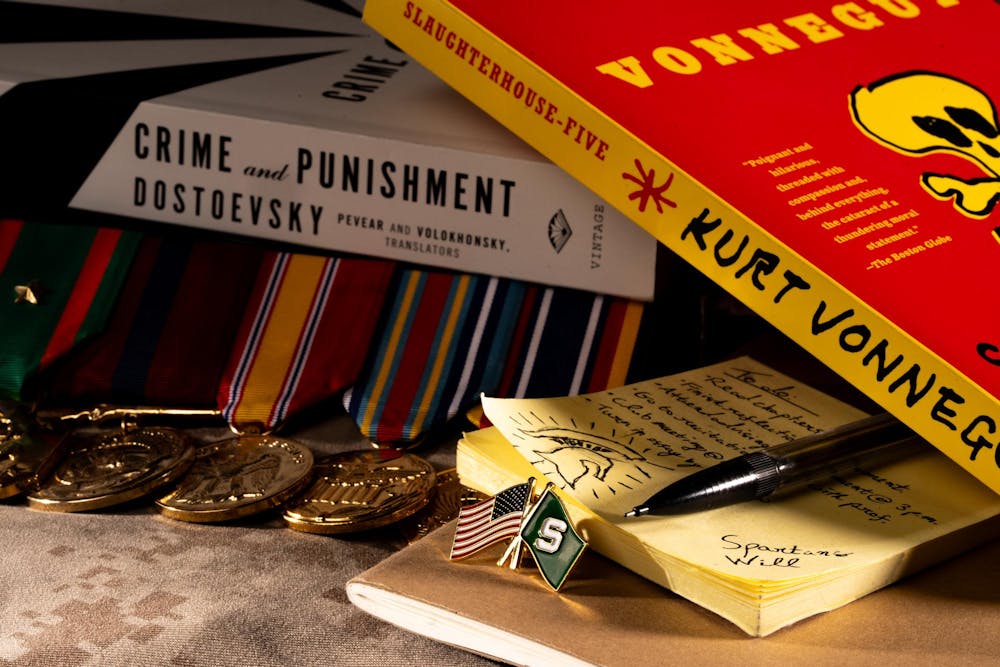

The formation of MSU as we know it today is often credited to the much-celebrated president atop the university through the mid-20th century, John Hannah. But in Branam-Drock’s reading, the real credit is owed to the congress that passed the G.I. Bill and the veterans who chose to use the funds in East Lansing.

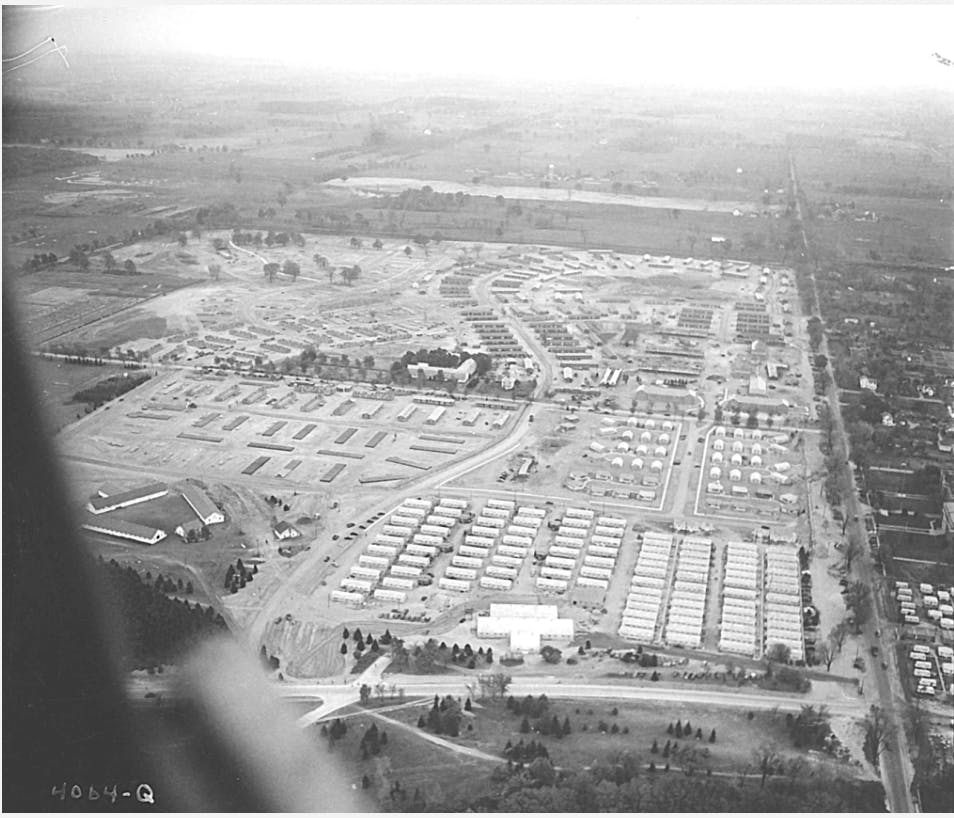

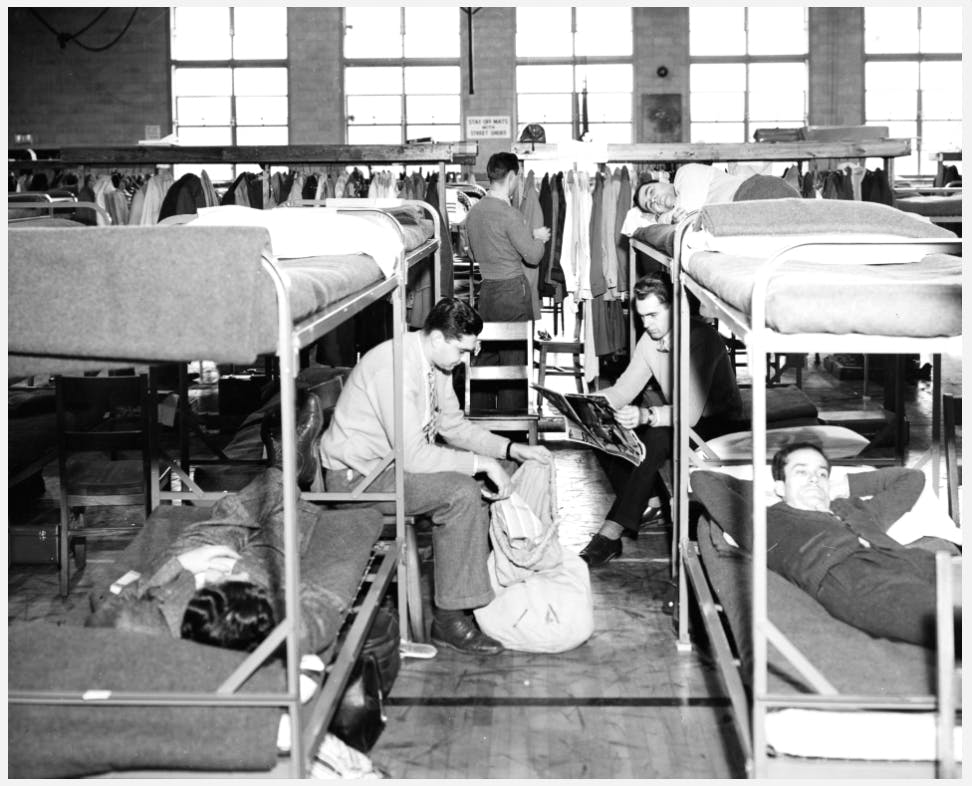

In 1946, as soldiers returned home and started accessing the landmark legislation’s benefits, MSU’s enrollment doubled. The university put hundreds of bunks in Jenison Fieldhouse and erected vast fields of trailers and huts around campus to house the thousands of new students. The explosion of enrollment allowed the administration to hire 250 new faculty members. Building on that growth in subsequent decades, MSU transformed from a regional agricultural college to a national research university.

"MSU really wouldn’t be what it is today without student veterans," Branam-Drock said. Lamenting the issues facing G.I. Bill users at the university today, he said, "It adds some salt in the wound."

Today, enrollment is again rapidly increasing for military-affiliated students. The last decade has seen their population swell from 705 to 2,489. In that period, they've generated over $300 million in tuition for MSU, according to data from MSU’s Center for Veterans and Military-Affiliated Students.

Around 1,000 of those students use the G.I. Bill to pay for their education. Some are veterans; others are dependents of veterans or active-duty service members. Their tuition amounts to around $7 million in payments from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to MSU each year, according to the center’s data.

Every semester, School Certifying Officials at MSU have to approve each payment made to every student. They act as a sort of liaison between schools and the VA, verifying that funds are spent as intended by examining students' status and enrollment information.

Certification involves multiple steps and numerous forms. In Branam-Drock’s experience, "It’s not a click of a button … it’s very bureaucratic, maybe it’s even inefficient."

"But, it works if there’s enough people," he said. "That’s the issue with MSU right now, just not having enough people."

Consequences of delays

The most recent guidance from the VA recommends that schools employ one full-time certifying official for every 125 students using G.I. Bill funds. At MSU, the current ratio is closer to one official for every 500 students.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

That shortage has led to persistent delays for students, who often wait months between applying for G.I. Bill funds and actually receiving the money.

The issue presents a regulatory risk, according to a recent memo from the student veterans center. Michigan’s State Approving Agency could launch a Risk-Based Survey of MSU, which are “deep investigations into university practices … with sometimes as little as 48-hour notice before a team of investigators arrive.” Failure could cost MSU its ability to use G.I. Bill funds altogether, the memo warns.

More broadly, the delays have had a real effect on students. A recent survey administered by the student veterans center yielded troubling results, according to a copy of the responses obtained by The State News through a public records request.

A few respondents reported tapping into their savings to cover costs like rent and tuition. Another said they’ve had to "rely on my mother, who can’t afford it." Others said they had to take on credit card debt or loans. Some just went without.

"I have gone hungry, homeless, and my studies have suffered in the beginning of the semester," one student reported. Another wrote that, "If (payments) continue to be delayed, I do not know how I will pay for my car or food."

Some tried to defer expenses, waiting until late in the semester to buy textbooks or required online assignments, for example. But those tactics brought their own consequences, with students saying they missed assignments or failed to understand key concepts in the interim.

The academic consequences were especially acute for the veterans who were supporting spouses or kids of their own, with some respondents reporting that they chose to prioritize their family’s needs over things like tuition or textbooks.

Those who took on jobs to cover expenses while waiting for payments were frustrated too. Some noted that the G.I. Bill is designed to support tuition and living expenses so veterans can truly be full-time students.

"It can be disheartening when I am working every day towards my career goals, but feel those who control my finances are not holding up their end of the contract," one student wrote in response to the survey.

That "contract" was first presented to some student veterans in simple terms, and served as a driver in their decision to enlist altogether.

"The G.I. Bill is designed so that we can be full time students," said Kyle Hiner, a journalism student who served for 10 years in the Marine Corps. "It’s written so we don’t have to focus on having to balance a full time job with being a full time student."

"I was 21 when I enlisted, and I was just like ‘Yes, I want that,’ it was my biggest thing ... We’re all promised that, if we get out honorably, we will have this privilege."

Beyond just G.I. Bill users, the certification issues have held up funds for other veterans at MSU.

Jay Velez, for example, told The State News he struggled to get timely approval of a scholarship that covers tuition for permanently disabled veterans. Staff in the financial aid office weren’t familiar with the program and a certifying official took months and pressure from the university ombudsperson to approve the funds, said Velez, who studies history and social studies education, hoping to be a high school teacher.

Education junior and U.S. Army veteran Jay Velez studies in the Student Veterans Resource Center on April 11, 2025. Velez was medically separated from the Army after 22 years of service when he developed issues with his eyes.

Last year, Velez didn’t get his spring semester funding until August, three months after classes ended, he said. The delay created a hold on his student account. "I ended up taking a bunch of really trash classes fall semester because I couldn't pay in time," said Velez, who served for over 20 years in the Army and lives in Ann Arbor with his wife and sons.

MSU highlighted Velez in a press release issued by its fundraising office.

"MSU came to his aid by providing financial assistance through the Disabled Veterans Assistance Program," the release said. "Thanks to the connection, Jay says he can pursue his career aspirations, post-military service, with greater confidence and peace of mind."

‘Lip service’

Patrick Forystek, director of MSU’s Center for Veterans and Military-Affiliated Students, said he has been pushing MSU to hire more certifying officials since 2020. So far, he’s gotten nowhere.

In a recent memo sent to his supervisors, he wrote that MSU would need to hire six more officials to comply with federal guidance. But he pleaded that, "realistically, 1-2 more full-time certifying officials would dramatically impact our deficit and reduce the funding delays."

Students have been lobbying for a change too, with leaders of MSU’s Student Veterans of America chapter (SVA) meeting with the Board of Trustees and multiple senior administrators, including President Kevin Guskiewicz. They too fear their pleas are being ignored.

"It’s all lip service," said Hiner, who is the SVA’s president. "We get told updates, ‘oh we have these updates, we’re working on this.’ But it’s been two years with no action."

The meetings with MSU’s leaders always go the same way, Hiner said: lots of notetaking, claims they’ll look into the issue, words of support, but, thus far, no actual action.

"I told (Guskiewicz) directly, even one more would make a huge difference," said Branam-Drock, who’s also in SVA. "I told him to his face, we need at least one more. If you want to make a change here, that’s something that’s so easy."

After a conversation with Guskiewicz, a Zoom meeting was arranged with Mark Largent, the dean of undergraduate education, and Vennie Gore, then the vice president for student life. The students hoped that conversation would be the start of real action, but they left more frustrated than before, said Hiner.

The administrators promised, again, to "look into it," then criticized the Powerpoint presentation used by the students, according to Hiner and Branam-Drock.

"(Largent) said, ‘here’s my critiques, you should add X, Y and Z to these slides’, not addressing the issues at all, just saying how our presentation could have been better," said Branam-Drock.

Reached by The State News, Largent said his goal was only to "successfully press for changes that would improve the certification process."

"One might perceive constructive advice to be 'criticism,' but I did not feel like anyone left that meeting upset," Largent said. "I provided advice about how they could sharpen their argument as well as direction about exactly who at MSU had the authority to solve the problem."

Largent said that he and Gore were the wrong people to ask about the certification issue. They "could advocate for changes," but the only person who could actually make them is Dave Weatherspoon, the vice provost who oversees the registrar’s office, where certifying officials work.

Weatherspoon told The State News his office is "in the fact-finding phase of our continuous improvement initiative to better serve our VA students."

For the students, the problem is urgent. They’ve been able to deal with the payment delays, but say some of their peers have opted to drop out amid the financial stress. The issues with certification are frustrating, and finding a job usually pays off quicker than trying to finish a degree, Hiner said. "It’s sad when you know people who thrive here, and then they get stiff-armed by the whole administrative burden of getting certified."

They tried to build support among other student organizations, but said those efforts were largely fruitless. The SVA is technically a member of the Council for Advocacy of Marginalized Students, which is part of MSU’s undergraduate student government, ASMSU. But Hiner said his group has gone into dormancy with the alliance, retaining its technical membership but not attending meetings or participating in initiatives. The other students involved weren’t particularly interested in the SVA’s issues, he said.

Other campus groups have removed themselves from the coalition in recent years, citing a lack of communication and general ineffectiveness. Asked about SVA’s experience, Branam-Drock said "it felt like a giant waste of time to listen to a bunch of people yell at each other about resolutions that don’t do anything."

‘We feel so bad for them’

Student veterans stressed that they have no animosity toward the two certifying officials MSU does have. If anything, the issues have made them appreciate them more. "They bend over backwards for us," Hiner said. "We feel so bad for them."

"They’re in a consistently overworked and underpaid situation," Branam-Drock said. "It’s not them, it’s a system issue."

The State News reached out to the certifying officials, but they either did not respond or passed the request off to a colleague, who subsequently did not respond. A university spokesperson provided The State News with a statement saying the officials have "decades of experience in this process and are dedicated and committed to offering exceptional service to our military affiliated students."

"We recognize the challenge of limited human resources and the lack of system tools," spokesperson Amber McCann wrote in the statement. "This limitation is not a reflection of the value we place on VA students, but rather a result of broader institutional constraints."

McCann said that the delays "are impacted by additional reporting requirements implemented by the (VA), which have increased administrative responsibilities and processing time."

Forystek, the director of the resource center, questioned her defense. New reporting requirements were what prompted the VA to create the recommended ratio in the first place, back in 2020, he said.

"It's very confusing to me," he said. "It's similar to the language the VA used to say why we needed the ratio, now it seems like she's using that as justification for a reason why we don't."

Journalism junior and U.S. Marine Corps veteran Kyle Hiner chats with Ian Knapp, an employee in the Student Veteran's Resource Center on April 11, 2025. Knapp, a U.S. Army veteran, works in the SVRC to coordinate events and services for student veterans like Edward.

‘I’m taking care of my veterans’

The students said they’ve found support with each other and through the resource center. In interviews with The State News, they effusively praised Forystek, its director. But, they framed that community as a sort of a triumph despite an apathetic administration, not a sign of commitment from the institution.

The center features a donated pantry of snacks, a few study rooms, and a tidy common area. Students gather there to watch games on TV and sometimes host tailgates just outside. The operation is largely donor funded, said Forystek, adding that they've only received about $28,000 from MSU since it opened in 2015. The center just hired its second employee, a move questioned by some students.

"When we met with the president or the board, we told them, ‘Hey, having an extra employee in the (center) is all well and good, but if you really want to make a true impactful change, you need to hire more certifying officials,'" Hiner said.

The walls of the center sport an array of plaques and certificates commending MSU’s support of student veterans. The Michigan Veterans Affairs Agency, for example, has for years recognized the university with its highest mark for Veteran-Friendly Schools, a gold-status. Students, however, said they aren’t sure if MSU has earned the praise.

"(Forystek) did the marine thing, and he’s just like, I’m taking care of my veterans," Hiner said. "This is what, in-house, taking care of your boys looks like … but it’s not the whole university."

Forystek himself has lobbied for markers like the gold-status to account for certification issues, he said, potentially jeopardizing MSU’s status if the situation doesn’t change. (The arbiters have not updated their criteria, Forystek said.)

For an example of true university investment in student veterans, look at Indiana University, said Velez, the history student who struggled to get certification of his scholarship for disabled veterans. There, student veterans have a building on campus, which houses both supportive resources and the certifying officials. Their ratio is close to one official for every 175 students, according to the director of their Center for Veteran and Military Students.

"There are places with a university driven-program, where this is more like (Forystek) clawing at anything he can get for us." Velez said of MSU’s center. "This is all (Forystek’s) doing, it isn’t really from external influence."

This year, students have wondered if they’re outgrowing the center’s small space in the basement of the student services building, Velez said. The military-affiliated population is rapidly growing at MSU, and the new staffer meant another study room would become an office.

At a recent meeting with MSU’s board, SVA students brought up their hope for a larger space, Velez said. They got a familiar reaction: notebooks opened up, concerned looks were exchanged, reassuring words were delivered with seeming care. Then, as far as he knows, nothing happened.

"They were immediately all like, ‘We got to get you guys windows!’ ‘Let’s get you on the second floor!’ or something like that," Velez said. "But again, I think it’s just more lip service."