The death of the humanities. The undying "well, what are you planning on doing with that?" This perceived ‘death’ has plagued students in these fields for as long as they decided that math, science and business weren’t for them.

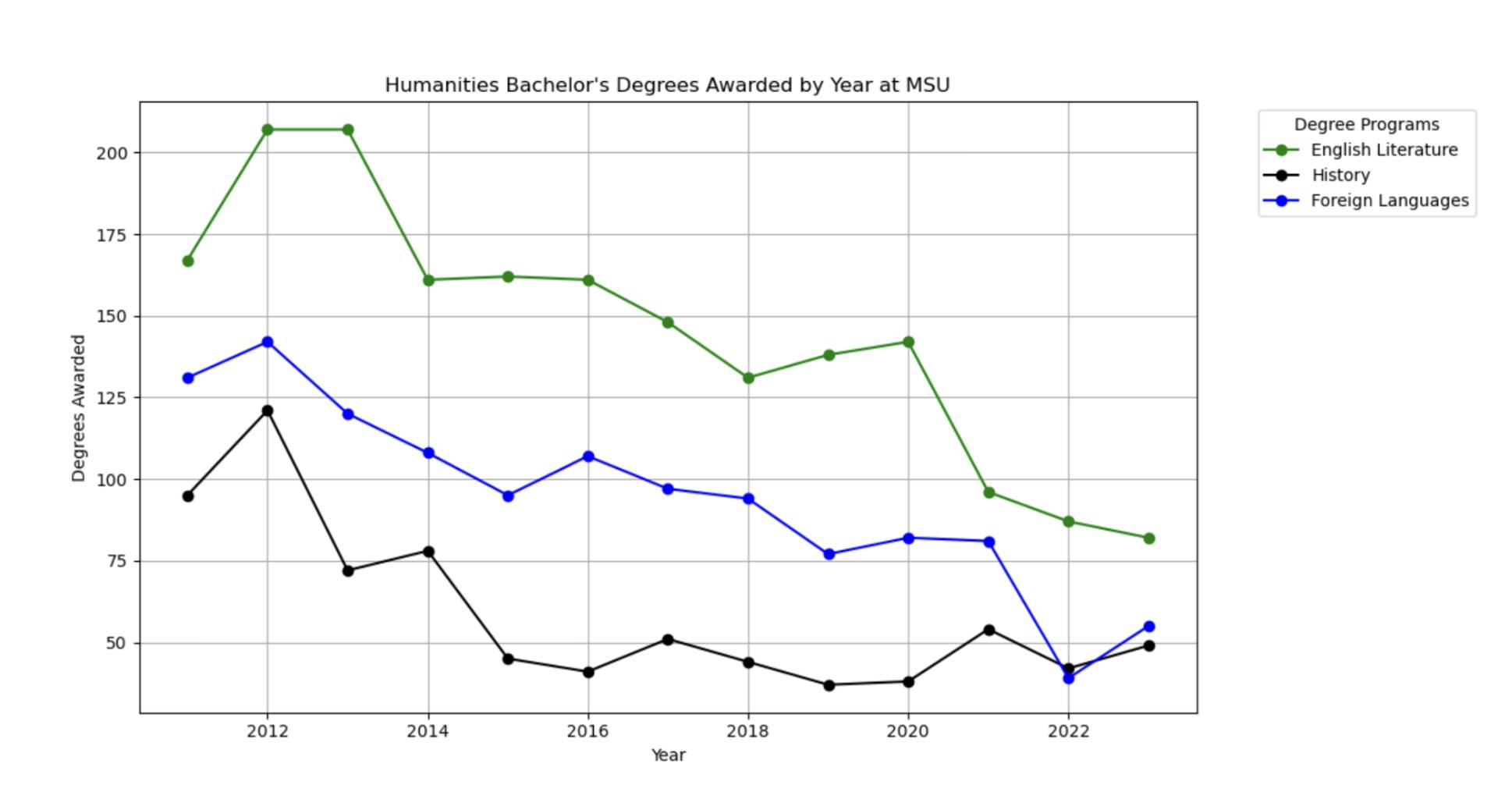

The reasoning for a decline isn’t entirely clear — federal mandates, poor administrative handling, artificial intelligence and Gen Z’s short attention spans have all been made culprits. Some scholars have questioned whether a death is even taking place at all. Regardless, there’s a trend looming in humanities classrooms. Fewer bachelor’s degrees are being handed out by the year, according to data from the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

The same trend is occurring at MSU. Data we collected from the National Center for Education Statistics shows bachelor’s degrees being awarded in fields like English and history have all been cut in half since 2012.

Regardless of whether the trend indicates some sort of dying process, many have begun to interpret it as such. So as two undergraduate English students, we decided to do the uplifting work of investigating this slow death, searching for something or someone we could hold responsible — talking to administrative faculty, professors, students and even our computers.

An issue with the system?

Many of the first fingers were — and have been continuously — pointed at the system itself. For people ascribing blame, the decline of the humanities represents deeply-embedded failures of capitalism, as well as the collective shift of viewing higher education as job training. More recently, the Trump administration’s funding cuts are affecting education across disciplines — and the humanities are nowhere near exempt.

In an email we obtained, Acting National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Chairman Michael McDonald wrote to South Asian American Digital Archive leadership about two weeks ago, "Your grant no longer effectuates the agency’s needs and priorities and conditions of the Grant Agreement and is subject to termination." The eerily-dystopian message continued, “the NEH is repurposing its funding allocations in a new direction in furtherance of the President’s agenda."

But the seeds for the decline were sown long before Trump took the oath of office for a second time. Seeds that contributed to a wider belief that the humanities have no real use in society.

The shift became prevalent when universities began emphasizing U.S. News & World Report rankings and job market directives over education for the sake of education. University of Houston professor Robert Zaretsky referred to the phenomenon as what he called "'consultization,' the morphing of college administrations into management-consulting firms, charged with improving the existing business model of higher education,” in a 2023 opinion piece published in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Emphasis is placed on the degrees that bring in the most revenue, not just for individuals entering a given market, but for researchers too. It’s no secret what makes the big bucks, so degrees that aren’t profit-driven are easy to devalue by members of the current presidential administration.

Or it’s possible that the roots of the issue go back to when the United States government first enlisted the help of professors at University of California, Berkeley to build the atomic bomb, cementing the idea that the government can fund higher education for the sake of national security. Or maybe the issue began when the idea of the business college was conceived, proving to students and professors that higher education could be a type of job training.

In 1944, C.B. Hutchinson, the then-President of the Association of Land-Grant Colleges delivered a speech at its 58th annual convention in which he seemingly predicted the future, speaking to the role of the humanities as a crucial part of every student’s education in the post-war era. "Land-Grant Colleges and Universities will need to lay more emphasis on that part of their original charge — the liberal education of the industrial classes," he said. "Only if such intellectual interests and habits of thought are aroused will the students have the stimulus and the power to continue to explore, on his own initiative, new ranges of subject matter and in later life to deal intelligently with fresh situations and problems as they arise."

Without properly introducing the humanities into a practical education, he argued, skills "essential to (the country’s) survival" would erode.

In this way the death may have been a ticking time bomb since the first English class opened in the United States, a bomb whose timer is just now being set off by the current administration. As Audre Lorde wrote in 1977, "within living structures defined by profit, by linear power, by institutional dehumanization, our feelings were not meant to survive."

More applicable than we thought

MSU Interim Provost and Executive Vice President of Academic Affairs Thomas Jeitschko didn’t quite know when it started, but he finds the trending decline concerning. There seems to be a fundamental misunderstanding from outsiders when it comes to what humanists actually do, which is due in part to the idea that "you don’t become a professional English-er," as he put it. There’s no obvious career path at the end of most degrees as there would be for an engineer.

The common conclusion, then, is that humanists don’t get jobs.

But he said that idea is just wrong. Successful people in upper and middle management frequently have humanities degrees, as they’re valuable in training thinking for "complex interdependencies."

"Let's say I know how to program in COBOL, that's an identifiable skill," he said. But "those are the types of skills that can depreciate over time." The world can move in a different direction, or if the user doesn’t actually utilize the skills consistently then they’ll slowly fade from their skillset. Jeitschko argued that the skills the humanities provide are more broad, and harder to lose over time. The issue, then, is the humanities’ frequent inability to properly market itself or make itself heard and he admitted that administrators can often fall short.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Going back to the university’s founding, MSU’s land grant status meant that practical skills like farming were put in direct conjunction with liberal arts studies, providing an interesting, new model for higher education. It bridged a gap that existed between higher ed institutions and working class farmers. While the world looks different than it did in 1855, the base model has persisted. Jeitschko said this model of higher education leads some people to think the arts and humanities aren’t as important, or that MSU is more of an agriculture or STEM-focused institution, which is not the case.

Empirically, humanists fare fine in the workforce, with the unemployment rate for majors in Michigan sitting at around 4%, only one percentage point larger than the 3% unemployment rate for engineers, according to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. They also earn more than the median salary in Michigan.

But over the past couple weeks we’ve come to realize that, regardless of employment rate and salary, the justification of the humanities using such metrics only feeds into the idea that legitimacy might only be attained by how well it fits into the capitalist system. Because this justification only exists for as long as that kind of labor is needed, the argument is lost when there is no longer a use for that kind of labor — or when it becomes automated.

Jeitschko understands the concerns raised as a result of the rise of AI in creative work, but he expressed that he doesn’t see a reactionary approach to the subject to be particularly productive. "AI is here, and it will be an integral part of what we do," he said. Rather than flat out rejecting that, he wants to question how we can respond to it.

For the Integrative Arts & Humanities and Integrative Social Science programs, MSU’s gen-ed requirements in the humanities, Jeitschko said the programs are currently undergoing a committee review for the purpose of modernization. One of the things he wants them to consider is where AI is going to fall into the curriculum.

He noted that, in general, higher education is "not particularly nimble," which causes challenges when navigating subject matters while they are evolving so quickly. Sometimes the pace of a subject’s evolution overshadows the subject itself, which poses challenges for curriculum development and engagement.

For a lot of MSU students, the gen-ed IAH and ISS classes are the most exposure they’ll get to the humanities. So perhaps that’s where the solution lies in making a case for these fields and helping people understand what it is humanists do.

As it stands now, if gen-ed humanities courses do not give students enough of a reason to care about the material, or don’t sufficiently engage with the material in a way that invites intellectual stimulation, then people don’t have a reason to think that the humanities are ‘worth it,’ no matter how important a general education of the humanities is to their education.

Studying the humanities now is different than it was a few decades ago. Jeitschko, who has two college-aged children, was surprised to see one of them picking up and reading a book. He rarely sees it anymore these days. And yet he doesn’t necessarily see that as a bad thing for the younger generation.

Like AI, he didn’t want to look at Gen Z’s interactions with technology as something to necessarily fight against. "There's a lot out there that's very superficial and might not have a lot of intellectual value, but that doesn't mean none of it (has) important qualifications. And it's part of the world that we now live in that humanists are studying and learning and teaching us about what it means," he said before showing us the picturesque view of the Red Cedar River outside his window.

'Well, what are you going to do with that?'

It was important, of course, that we talk to a humanities student — someone pursuing a degree in a 'dying field.' English senior Suhasini Iyer told us she bounced around a fair bit before deciding on English as a major, but ultimately was drawn to its versatility.

Iyer agrees the humanities are dying to an extent. Her plan for next fall? Attending graduate school for business — her main reason being hireability. While she believes in her undergraduate choice, Iyer said she understands "the fear" of staring into the job market.

As a humanities undergraduate student, and one who found herself in a handful of creative writing classes, Iyer’s relationship to AI is complex. And, contrary to a lot of conversation among students in these spaces, it’s far from a complete negative to her.

Iyer said creative spaces are certainly vulnerable to AI’s exploitation, and to those who want to streamline creative work to make it look and feel more corporate. “I don’t believe in shortcuts and that kind of stuff,” she said.

And while she understands the concern of intensely exploiting creative work or taking jobs, Iyer says it’s not AI’s main purpose, and might just be an unfortunate result of misuse. At the end of the day, “the part that makes writing interesting (is the) human experience put into it,” and she doesn’t believe AI could ever truly replicate that.

It goes without saying that AI use among students exists outside of the classroom as well. As an undergraduate consultant on campus at the MSU Writing Center, Iyer has seen firsthand how AI can make assignments more understandable and doable for students. She says as long as people use it to help them do work and not fully complete it for them, it can be a tool — a way to reframe directions, create outlines for academic papers or help guide a piece’s structure.

"I'm a creative and not everybody is," she said. And while she doesn’t necessarily believe in using it for creative purposes, she doesn’t hold it against people who use it for other elements of writing — like formatting or thesis statement development.

She connected these ingrained beliefs about the humanities’ lifespan and relevance with the issue of capitalism, saying federal attitudes toward creativity are dominant and at play — especially under the current administration. As we’ve discussed, careers that don’t automatically signal money-makers under capitalism are deemed illegitimate or useless.

She gets when people say things like “oh, you’re an English major? What are you going to do with that?” but thinks it stems from a deeper place — one of accidental, inherent, anxious belief. The problem has two parts to her: People are being told the humanities aren’t interesting or important, and then they believe it.

‘Panic data won’t help'

We spoke with Divya Victor, director of the Creative Writing program, associate professor and writer. The first thing she did was kindly contradict the intention of this piece: “When there are statements like ‘humanities are dying,’ you always have to ask for whom, because death is, in a weird way, relative and not absolute. Because it's a metaphorical death, right?”

We figured this was a good point, and a large flaw in our original question: The humanities couldn’t be entirely dead — we were here speaking with a highly decorated, flourishing humanist as two students also pursuing and engaging with degrees in the field.

Victor called what we opened with “panic data,” and said it wasn’t necessarily helpful to people in her position. She said that for her, at age 42, the humanities are “more alive than they’ve ever been.”

“And that's not just a kind of subjective delusion,” she followed. Victor said her perception of life within the humanities comes from her perception of goals she is reaching in regard to undergraduate education, her personal artistic output and “the relationships and networks that we are building together as humanists and writers and artists.”

According to Victor, MSU has more English majors than it did five years ago, and the relatively young creative writing minor grows by the semester as well — with the department actually seeing more applications than it can admit. But, as we predicted, not all statistics are growing.

While she doesn’t love the “panic data,” Victor did say dwindling federal funding toward upper administration has resulted in a lacking faculty hiring lines, tenure tracks and compressed salaries. She encouraged us to consider who “isn’t being allowed” to thrive in the humanities, and said numerical data cannot paint a comprehensive conclusion about the humanities.

On the topic of federal funding, Victor went on to reference NEH grant funding having recently been pulled as part of the Trump administration’s plan to make continuous cuts from research funding and grant allocation. This example prompted her to reaffirm that the humanities are not dying, but are certainly under threat, one she wanted to distinguish as “human made.”

Victor is an example of someone who has built a life as a humanist — consuming, teaching, planning and writing, just to name a few. When we asked her how she looks to empower students in these circles to acknowledge these threats and declare a major in the humanities anyway, she lit up. “I mean, that word is so beautiful: to ‘declare’ it. To declare a major is such a stance. It's such a way of sticking a claim in your life,” she said. She said the first step, then, is to work on affirmation that strengthens a student’s capacity for choice.

She has many family members who wanted to pursue creative disciplines and could not, cousins who wanted to be chefs or dancers and instead entered STEM. “I think I grew up in such a context where the power to see what we want has to be bolstered and taught as a skill at a very early moment in one's life,” she said.

She has long valued not only having a choice, but having been empowered and taught how to choose — a series of thought that, if not taught in public education or among family, must come from undergraduate education. The responsibility of these spaces and provided resources, Victor believes, is to teach students “not only believe in themselves, but to even come to discover what they believe so they can believe it.”

The Creative Writing program’s slogan is “Living, Breathing, Writing.” Victor said the collective “we” of faculty and educators are responsible for demonstrating to young humanists that their living is deeply connected to their creative expression.

Earlier this academic year, the program director founded the Writer’s Studio in Wells Hall, a comfortable space open to all majors for working and collaborating. Hosting a small library, bulletin board of student-penned writing prompts and snacks, the space is open to any major nearly all hours of the day. The studio is an example of something that can be physically implemented to empower students, as Victor explained that spaces that offer a sense of alignment between physical and cognitive and imaginative needs are imperative for writers to believe they deserve to be doing this work and are valued in their pursuit of it.

Not only that, but a space solely devoted to creative expression can enable students to tackle topics they might not feel “energetically and spiritually” empowered to elsewhere. “How are you going to question the state, and question capitalism, at Starbucks?” she asked.

While Victor confirmed she loves teaching the groups she does, and feels fortunate to share the space with people who have entirely chosen to be there, she has definitely noticed a shift in attention spans and consumption intention. Even when people are reading, she says, they are doing it to be ‘right’ and affirm their own beliefs.

“And that's not why we should be reading. We should be reading to be totally astonished, a little bit confused, and to question things, right?” she said.

Though students aren’t necessarily to blame in any of this, Victor said. She acknowledged that the day to day lives of college students in this economy have, without a doubt, resulted in an impacted possible creative output. The pressure placed on students to work multiple jobs to achieve relative financial stability while pursuing a degree “has an impact on your creative education life” which, Victor added, is indeed a “working life.”

After all this, we asked her to discuss AI, which she bluntly said was “complicated.” Her main concern with AI is not its presence, as she voiced she doesn’t believe we have ever lived in a creative time entirely free of technology, but rather one of consent, arguing that the circulation of “cheapened” reproduced work is an “impoverishment of the imagination” and terrible “pillage of our agency.”

When she used the term “AI mulch,” we really got the picture.

“It reminds me of all the events and histories where we have squandered our ability to see the future for all good,” she said. “It reminds me of the worst parts of history, because we're capable of such genius, and we have put it towards robbing other people of their genius and we've put it towards devastating the environment.”

AI has taken some heat here. It wouldn’t be fair to not let it defend itself.

Are we the first journalists to interview AI?

We asked AI (specifically Deepseek) to explain the death of the humanities and the primary causes. Maybe there was a hope it would turn on itself, maybe we thought it would tell us something we didn’t already garner from our handful of human sources. What it gave us was a decent blend of both.

“Do you think that generative AI is contributing to the decline of humanities fields in academia?” we asked.

“The impact of generative AI on the humanities in academia is a complex and debated issue," it said. "While AI isn’t solely responsible for the decline of humanities fields (which have faced challenges like funding cuts, declining enrollment, and shifting cultural priorities for years), it is accelerating certain trends and forcing a reckoning."

It listed how generative AI might contribute to the decline and provided counterarguments. On contributions, it said AI reinforces biases toward STEM fields, automates soft skills, erodes trust in human creativity and could redirect research funds away from the humanities.

Just below, in an immediate counter, it ran us through a slew of reasons why AI might not be the threat we framed it to be: the humanities being questions rather than solvable answers; AI introduces new interdisciplinary opportunities and educational fields; and it exposes the limits of technology and reminds us why human judgment matters. The technology also highlighted that this “crisis” is not new but rather one that has been happening since the 19th century. Humanities have persisted through tech booms before, and they could technically do it again.

Then, in bold: “The Real Threat: Instrumental Thinking,” it said.

Underneath, it said the decline isn’t inevitable, but will keep happening if universities continue to frame education as job training. “What’s your perspective?” it asked us at the end of the response. “Are you seeing this play out in your own academic or professional context?”

Hey, we’re the ones asking the questions.

“What are your thoughts on students abusing AI for creative work? Is that contributing to the decline?” we asked.

“The abuse of AI for creative work by students is a serious concern—not just for academia, but for the broader cultural value of creativity and critical thought. While AI can be a useful tool, its misuse (e.g., generating essays, stories, or art without genuine engagement) risks eroding the very skills the humanities aim to cultivate," it said.

It, once again, asked us a bigger question. What is creativity for? Like Jeitschko, it challenged the notion that the humanities are as simple as painting pretty pictures or reading a lot of books, but instead exist to cultivate intellectual thought among humans.

The final ‘verdict’

If you’ve made it all the way here expecting a concrete culprit, we have bad news. It looks like it’s a combination of everyone and no one. Humanities are declining to those who believe the humanities are declining. The collection of disciplines is largely alive to those who pour into it and see it as such.

The distinction between threats and death must be made; students must be empowered to connect their founded wants with daily practice and a genuine belief must be had in the work humanists do. And we should move through the “AI mulch” with caution.

Victor left us with some final thoughts on faculty in these spaces, but we think it just about covers everything you just read from us, too. She asked us to consider that we as students only see the “tip of the iceberg” when it comes to teaching practices exemplified in the classroom — which Victor said emerges from other elements like research, creative activity, values and philosophy.

“So keep that in mind when you think about the humanities are dying, because the roots are alive and nourished, because we're doing it right now,” she said.

Well yes, we guess we are.