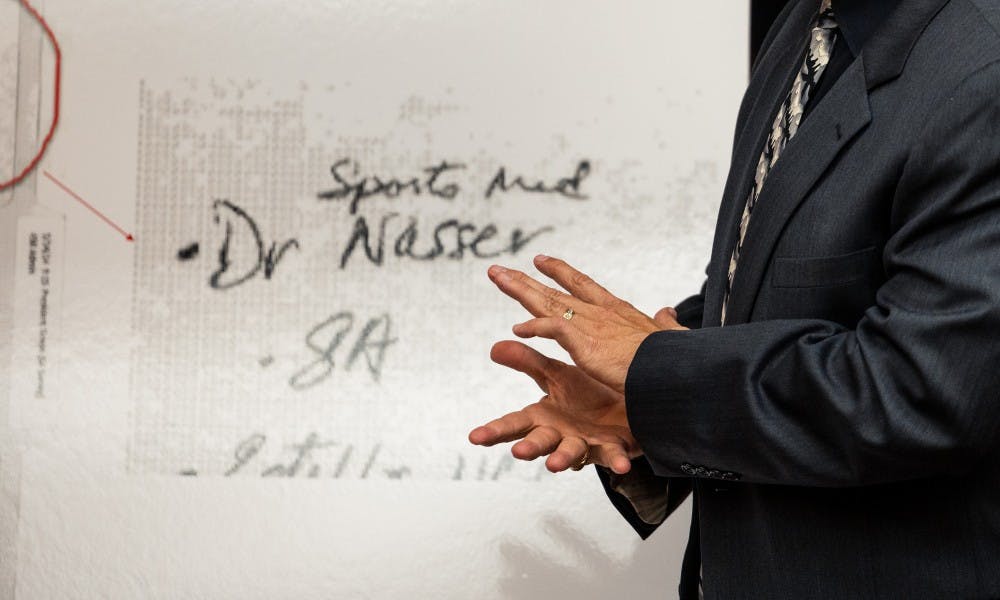

Thousands of recently released documents reveal that the university’s records-keeping, when it was needed the most, was laden with mistakes.

A former university president admitted she deleted personal text messages when an investigation required a probe of her phone. Nine investigatory files needed by an outside Title IX attorney went missing for months because a department didn’t organize its files.

And the very documents that reveal these missteps? MSU refused to hand them over to Attorney General Dana Nessel for years, delaying her investigation into Nassar and prolonging survivors’ hope of accountability.

Nessel concluded her investigation less than two weeks ago, saying the thousands of documents about MSU’s handling of Nassar contained information that was "embarrassing" for the university, but not "incriminating."

What was clear, Nessel argued, is that MSU wrongly withheld the documents for years.

Attorney client privilege?

MSU has long said the documents are subject to "attorney-client privilege," which protects communications between a lawyer and their client from being publicly released.

Many of the documents outlined the university’s communications strategy, not legal conversations. Others were shown not to be privileged by their own authors’ admission.

Kristine Zayko, MSU’s deputy general counsel, advised several MSU officials that their communications were not protected by attorney-client privilege.

" ... putting privileged & confidential on the top of these does not make them privileged," Zayko wrote to one colleague who had included the phrase at the top of an email about PR strategy. "They would still get released under a (Freedom of Information Act request) since they are not actually seeking any legal advice."

Zayko issued the same reminder to Trustee Dianne Byrum after she distributed a "privileged" media protocol for board members to consult during the heights of the Nassar scandal.

MSU Spokesperson Emily Guerrant defended the university’s withholding of the documents, saying that Zayko was giving university officials legal advice — which, in itself, would be considered privileged information.

Deleting, avoiding texts

In January 2018, as MSU’s general counsel was reminding employees to retain their communications for the newly-begun attorney general investigation into Nassar, former President Lou Anna Simon admitted she had a habit of deleting her text messages.

"As you are aware I have always treated text messages as the equivalent of oral communication and deleted," she wrote. "However, I did this with the understanding that all were available through a request that I could make or through legal avenues."

Simon’s husband, a facilities employee named Roy, had been doing the same, she later said.

"For years, he has answered all email he receives as soon as possible, often the same day, and then deletes," Simon wrote in an email to then Assistant General Counsel Brian Quinn later that month, adding that she didn’t recall using Roy’s belongings to communicate about Nassar.

Another MSU employee was seemingly trying to prevent such records from being created in the first place.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Kathie Klages, a former university gymnastics coach, told student-athletes "that they might not want to text back and forth about Nassar, that they should talk on the phone if they wanted to discuss," Zayko said in an email recalling a conversation with her in January 2017.

Klages was convicted in 2020 for lying to police about her knowledge of Nassar’s abuse, but the conviction was later overturned.

Missing files

In 2016, university staff discovered they hadn’t given the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights all the sexual abuse investigatory files an investigator had previously requested for a review.

MSU’s newly created Office of Institutional Equity quickly began an audit to see what else was missing, according to a memo sent to Simon about the error in March 2017.

The university found a total of nine files — including one about Nassar — that weren’t given to the investigator because the department that first compiled them failed "to implement any sort of file organization system."

Former university psychologist Gary Stollak, who surrendered his license in 2018 after failing to inform authorities of Nassar’s suspected abuse, also had a problem with missing records.

Stollak didn’t have access to his patient records because he destroyed them all, Stollak’s attorney, Peter Cronk, told MSU in April 2017.

"Stollak's home was broken into twice several years ago," general counsel Quinn wrote, recalling a prior conversation with Cronk. "One time, patient records were removed. So Stollak destroyed all his records."

Fight over documents' release

The university's withholding of the thousands of documents related to its handling of Nassar has been a source of controversy for years. The decision inspired a lawsuit and continual pleas from survivors.

Throughout it all, MSU defended its withholding of the records.

Trustee Renee Knake Jefferson, who read the documents before they were released, said in 2020 that the documents didn’t contain any new information about the administration's handling of Nassar. A year prior, East Lansing District Court Judge Richard Ball ruled that MSU had appropriately applied attorney-client privilege to the documents.

Without access to the documents, Nessel closed her investigation into Nassar in 2021.

But in 2023, with the election of new board members who voiced support for releasing the documents, Nessel reopened her investigation into "how and why the university failed to protect students" from Nassar’s abuse for so long.

In December of 2023, MSU’s Board of Trustees voted unanimously to send those documents to Nessel’s office.

Nessel completed her investigation and publicly released the documents nearly two weeks ago. But the move, not unlike MSU's record-keeping, didn't go smoothly.

Nessel's office had to temporarily remove access to some of the documents days after releasing them to the public, because the office didn't fully redact names and information about survivors in them. But even after the documents' rerelease, some survivors' names remain unredacted.

Administration Reporter Owen McCarthy and Senior Reporter Alex Walters contributed reporting.

Discussion

Share and discuss “How MSU’s faulty record-keeping of Nassar delayed scrutiny” on social media.