| Content warning: This article contains descriptions of sexual violence. The National Sexual Assault Hotline can be reached at 800-656-HOPE (4673). |

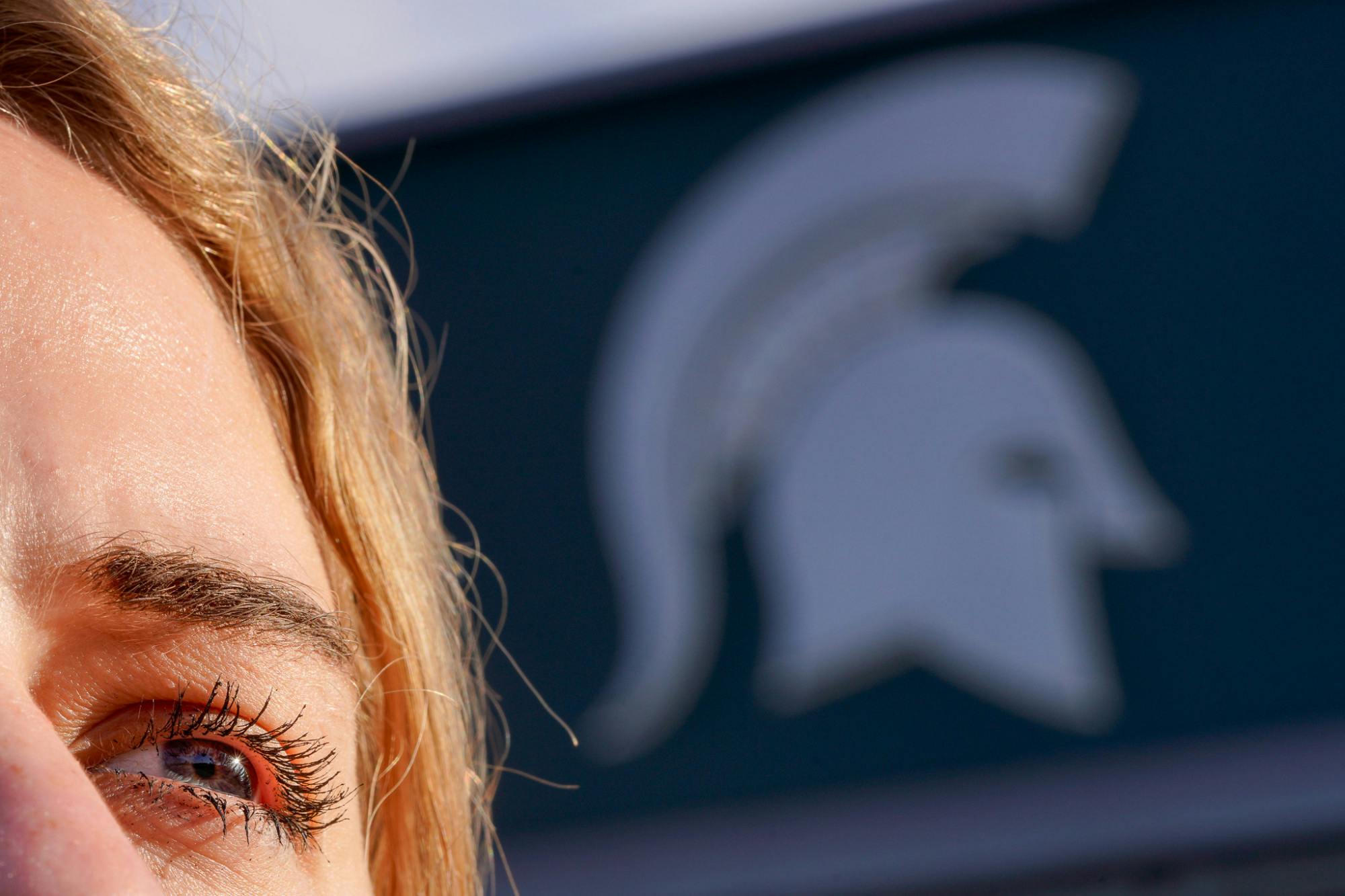

Two days after she was raped, Lilley Schatz walked into Michigan State University’s police department to report it.

She was led into an interview room and asked to recount the night.

Schatz did, trying to be as clear as possible about the traumatic details she was still making sense of.

At first, it went well. She felt trusted, like the uniform division officer taking her statement cared about what she was saying.

Then, she added something: the man who raped her was a member of MSU’s football team.

Suddenly, she felt the officer’s demeanor change. She no longer felt believed.

Worried by his perceivable doubt, she asked the officer if what she was describing was a crime. She says he told her no, that it was a “gray area.”

“At first he was taking me seriously, he was like ‘yeah, this is bad,’” Schatz told The State News. “And then as soon as I mentioned he’s a football player, now it’s a ‘gray area.’”

Schatz, 22, left the police station “sobbing uncontrollably,” doubting herself, wondering if “what had happened was really as bad” as she thought.

It was only the beginning.

Over the next 16 months, Schatz would attempt to work through both the trauma of what happened to her and the additional trauma brought about by reporting it.

She utilized MSU’s two systems for governing sexual violence: the police department and Title IX office.

In both systems, she encountered individuals who supported her, who believed her and helped her heal. But, she feels the institutions themselves largely failed her.

The police seemed to eventually take her seriously, but she was discouraged from pressing charges and putting herself through a nerve-wracking criminal trial.

Instead, she was told to just trust MSU and go through a supposedly easier Title IX process.

That seemed so promising. Schatz, a social work senior, said she believed the university she loved would surely protect her.

But, she would come to feel even more dismissed, disbelieved and ridiculed by the lengthy university investigation than she could have imagined.

She anxiously waited out months-long lapses in communication from MSU’s investigators, receiving multiple extension notices from the infamously slow Title IX office. She was retraumatized by a crude hearing process, and felt her words turned against her. And, in the end, she was deemed untrustworthy through a “credibility assessment” the nation’s leading sexual assault trauma expert calls “wrong” and “completely unscientific.”

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Schatz would also face resistance from MSU’s athletic department, with the athletic director and football coach ignoring her plea for answers and action.

She’s not alone. Schatz’s experience is the latest in a long list of cases where MSU discouraged and discredited survivors of reported sexual assault, especially by high-profile student-athletes.

Schatz is sharing her story and hundreds of pages of investigative documents with The State News, hoping her experience will inspire change at MSU.

She hopes to be a voice, not just for herself, but for "other victims who can't speak up."

A criminal case

When Schatz left the football player’s apartment the night of the assault, Sept. 15, 2022, she was not yet sure that she had been raped.

She met the football player on Bumble. In her messages to him, she was clear that she didn't want to have sex when they hung out. She told him that was off the table, that she wanted to be in a relationship and “didn’t want a hookup,” according to both their interviews with investigators.

In the messages, he was okay with that. But when they got together, alone in his apartment, he didn’t take no for an answer.

Schatz drove home bawling, she said, trying to get a hold of her roommate who was in an exam, unable to respond.

When her roommate arrived at their apartment later that night, she found Schatz on the couch “obviously stressed” and “physically shaking,” according to her interview with MSU investigators.

She could “tell by her face that something was wrong,” and asked her what happened.

Schatz told her how he kept touching her and how she kept saying no. How she felt scared by his size and comments about his firearms. How she felt “frozen” and “intimidated” and afraid to keep telling him to stop. How all she could think about was going home and how she eventually realized that wasn’t going to happen unless she gave in. So, she told him to “just f— me” and started dissociating, hoping she would get to leave.

“That sounds like coercion,” her roommate said.

She would later tell the investigators that she believed that was the moment Schatz realized she had been assaulted.

You can contact the reporter by email at alex.walters@statenews.com or call/text at (248) 979-5497

Schatz then called her parents, according to the MSU interviews, who said she should go to the hospital and get a rape kit, a type of medical exam used to gather and preserve the physical evidence of sexual assault.

Schatz listened and went with her roommate to Sparrow Hospital, she was “still in a lot of denial.”

“I just remember crying and crying and crying, not being able to tell them ‘hi, I’m here for a rape kit,’” Schatz said.

She was “overwhelmed and in shock.”

“It was really intense,” Schatz said. “You strip naked, they take your clothes, you put on a gown, then you lay on this like bed and they swab your whole body, and swab your mouth, and ask if they can take pictures.”

The procedure itself was a “horrible experience,” Schatz said. But, she says the people she encountered “made a difference” by being supportive.

She was examined by Sparrow’s SANE nurses, who are specially trained to treat sexual assault survivors, and was introduced to a victim advocate from EVE, a local nonprofit that assists survivors of sexual violence.

At the time, Schatz was still making sense of what happened, and not sure if it was something that should be reported to law enforcement or the university.

“At this point, it had just happened, and I didn’t really know if this was sexual assault,” Schatz said. “But the nurse I had was super nice. I told her everything that happened, and she was like ‘we should call the police right now, have them come here, and I can be there to help you talk to them.’”

But Schatz wasn't ready yet. She says she felt supported and understood the importance of reporting, but needed time to process what happened first.

Two days later, she felt ready.

She went to MSU police, with her dad for support and was interviewed by the uniformed division officer who told her it was a “gray area.”

The officer, Charles Wasson, did not return requests for comment.

Schatz thought that could be the end of it. She worried he was right, that it wasn’t a crime.

Then, she got a call from another officer, an investigator with MSU police’s special victims unit.

She says the officer – Det. Aaron Schroeder – told her the first officer was wrong, that what happened was sexual assault and that the first cop “shouldn’t have said anything about it because he’s not an investigator.”

MSU police declined to answer questions about the uniform officer’s interactions with Schatz. It did provide a statement to The State News saying “our officers, including our uniformed officers, are trained in victim-centered and trauma-informed practices.”

Schatz said Schroeder was completely different from the first officer she spoke to. He was supportive, and repeatedly reached out to her and her roommate over the ensuing weeks to see how she was doing and ask if she had any questions.

Schroeder also quickly brought the player in for questioning.

The State News is not naming the player because he was not charged with a crime or found to have violated policies by the university. The player, through his attorney, declined The State News’ requests for comment.

In an interview with the detective detailed in the police report, the player tells an alternate version of the story.

He said she initiated the encounter, that “she just started kissing me,” which led to consensual sex, according to Schroeder’s interview notes.

The player told him “I’m not a rapist bro, I’ve never (inaudible) a woman, I have three sisters, I could never do no type of s— like that, that’s crazy,” according to the notes.

Schroeder then asked him, if she initiated the intimacy, why would Schatz say he raped her?

The player said he suspected she was mad because he didn’t want to date her, that “she wanted more of a relationship, which might be why she’s angry.”

Schroeder’s notes say he then “asked (the player) if he could think of any other reasons why he thinks Schatz would be angry, (the player) said ‘cause I sold her dream out, basically.’”

The player then started asking Schroeder if he could contact Schatz. He advised him not to.

The player then said, “I wouldn’t even be mean to her or anything.” He said he just wanted “to know why she’s telling the cops” he assaulted her.

Schroeder again told him not to reach out to her.

That interview was the last time the player discussed the allegations with investigators. He would later direct all contact from MSU police to his attorney, Adam Sabree.

After the player was interviewed, Schatz emailed MSU police saying she intended to press charges. They sent her case to the Ingham County Prosecutor for review.

Schatz says she then received a call from a prosecuting attorney, Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Unit Chief Kristen Rolph.

Rolph was candid, Schatz said, telling her a criminal prosecution would be lengthy and stressful.

“She was just like, ‘rape cases are really hard for victims to go through, because you’re gonna have to do a trial,’” Schatz said.

That was an issue. Schatz didn’t want to have a public trial, or be cross-examined.

Then Rolph introduced another possibility: trust MSU, just go through the Title IX process.

Title IX is a federal law that mandates equality of access to education for men and women. Under it, sexual misconduct on campuses is not only a crime, but a violation of a student’s right to their education.

Because of that, universities are empowered to investigate and discipline incidents of sexual violence. At MSU, that’s done by the Office of Institutional Equity, or OIE.

“(The prosecutor) said I was 100% raped and that she thought (MSU) would 100% find him guilty,” Schatz said. The prosecutor explained that MSU’s Title IX process would have a lower burden of proof.

That assurance was enough for Schatz, who wanted to trust MSU.

Schatz grew up in East Lansing and her dad worked at MSU her whole life.

“MSU was always my dream,” she said.

Schatz also thought the university's recent reckoning with years of unchecked sexual abuse by disgraced doctor Larry Nassar would mean those in power were committed to doing right by survivors.

“After all the Nassar stuff, I was like ‘oh, they’re gonna take this seriously,’” she said.

So, she put her faith in MSU.

She declined to press criminal charges and cooperated fully with an OIE investigation into her allegations.

Today, more than a year after she made that decision, Schatz wishes she hadn’t been so optimistic.

A Title IX investigation

The OIE investigation into the reported rape had already started when Schatz decided not to press charges.

MSU police had alerted the university to the allegations when she reported the assault in September.

Schatz says the early conversations with the OIE went well. They gave her lots of information and resources, and were extremely communicative.

But as time went on, that changed. The responses to her emails got shorter or never came. Or, when she did hear from them, it was a notice that they needed an extension or a triggering, hyper-specific question, she said.

“You start out thinking ‘oh, maybe something will actually happen, they’ll believe me,’” Schatz said. “But as time went on, it felt like they ditched me.”

She also felt the effects of constant staff turnover in the OIE, which independent consultants have called a major factor in its dysfunction.

Outside of the Student Affairs and Services building, where the Center for Survivors is located, on Circle Drive in East Lansing on Dec. 8, 2023.

OIE cases are conducted by an investigator and the parties involved also each have advisors, who function like lawyers would in a criminal proceeding.

“I got a new investigator once, and I had to get a new advisor through MSU a few times because they all kept quitting,” Schatz said. “It was just frustrating, I kinda ended up being like ‘yeah, nothing’s gonna happen,’ I had no faith in it.”

Each new staffer would have to catch up on the details of her case, which Schatz believes contributed to the slowness and tedium of the process.

The football player declined to participate in the OIE process.

The player’s first attorney, Sabree, didn’t represent him in the OIE process because by the time it started, he had been elected a district court judge in Wayne County.

So for the OIE, the player was represented instead by Steven Haney, a high profile sports attorney.

Haney recently represented Eastern Michigan basketball star Emoni Bates when he faced felony gun charges and NBA Agent Christian Dawkins in a felony conspiracy trial described by ESPN as “the biggest trial in the history of sports,” according to Haney’s professional bio.

He’s also represented numerous NBA players as an attorney and agent, including MSU alumni Earvin “Magic” Johnson, according to the bio.

Haney issued one brief statement to the OIE saying the player “denies any and all allegations which have been offered by (Schatz).”

After all the evidence – Schatz’s multiple statements, her roommate’s statements, the player’s denial, and the MSU police report summarizing the investigation – was submitted, the parties were called to a hearing where the final details would be worked out.

The player and his attorney did not attend the hearing. A respondent advisor – an MSU employee who functions in OIE cases like public defenders do in the criminal legal system – appeared in his place.

Schatz said the hearing was “not a great experience,” particularly because she was put through a cross-examination by the respondent advisor.

The respondent advisor, Ralph Johnson, started by citing a portion of her first statement where she said she felt she had to have sex with the player if she wanted to go home.

“Help us understand why you felt that?” he said, according to a transcript of the exchange.

She said “he kept touching me and I kept saying no and then it was just escalating.” She said how he “got on top of (her)” and she felt “pinned down.”

Johnson asked her what she meant by “pinned down.”

She said he was on top of her and referenced his size. The player is over a foot taller than Schatz.

Johnson then asked her why she would say “just f— me,” if she didn’t really want to have sex with him.

She said she “felt like (she) had no other choice,” that she had to “just get it over with” so she “would be able to go home.”

Johnson kept pushing, asking her if she ever vocalized her desire to leave.

She said he was already on top of her at that point and he “wasn’t respecting my other boundaries and no’s, and I didn’t want him to hurt me or anything, just because he’s so much bigger than I am.”

“I really just wanted to go home,” she said.

Later in the cross-examination, Johnson came back to the fear she said she felt. He asked her what specifically made her feel she couldn’t just leave the football player’s apartment.

She again said his size, and that he was on top of her.

She also added how after he assaulted her, the player was standing between her and the door, which is “why (she) stayed for so long afterwards on the bed crying.”

Johnson continued, asking her if something else happened that would have “caused (her) to feel fear or restricted in any way?”

She referenced a conversation they had before he assaulted her, when the player mentioned owning guns and how he could “shoot up” her ex-boyfriend’s house.

That hearing testimony would be a major factor in the decision in Schatz’s case, which found that there was not sufficient evidence to say the football player raped Schatz.

The decision was made by a resolution officer – an independent party outside the university – who reviewed the hearing and evidence.

The resolution officer in Schatz’s case, Columbus attorney Jessica Galanos, said Schatz was uncredible because of how many questions it took for her to bring up the guns.

Schatz first described the guns in an earlier conversation with MSU police, saying it contributed to her fear of fighting back, and it was an “intimidation tactic.”

Galanos writes in her decision that because it took four questions for Schatz to bring up the guns, it undercuts the credibility of the accusation altogether.

“It is difficult to reconcile (Schatz’s) delay in referencing the gun conversation with the fact that she told (MSU police) that (he) used the topic as an ‘intimidation tactic,’” Galanos wrote in her decision.

Jim Hopper, a Harvard Medical School teaching associate who studies how sexual assault affects the brain, said Galanos’ conclusion is “atrocious” and that he’s “not aware of any scientific basis” for determining the truth of a statement based on how many questions it takes for someone to bring it up.

If anything, Hopper said, the specific questions posed in the cross-examination are the kinds of stimuli that could trigger further memory, and prompt someone to bring up a contextual detail like the fears about the guns.

“It’s ridiculous to think that undermines her credibility, when what happened is actually completely in line with how memory works,” Hopper said.

The guns example is just one part of the “credibility assessment” that Galanos conducted on Schatz, looking for any differences in her statements to investigators or areas where what she describes is different from what a “reasonable person” would perceive.

Through that assessment, Galanos concluded that Schatz was not credible.

The tactics Galanos used to reach that conclusion are completely out of line with what is scientifically understood about memory and trauma, Hopper, one of the nation’s leading experts on the subject, said.

For example, Schatz did not describe forced oral sex in her first statement to MSU police, with the officer she says told her it was a “gray area.” She did then describe it in her later statements to MSU police and the OIE.

Galanos said that “undermines the reliability of both (Schatz’s) prior statements and (Schatz’s) second written statement to OIE.”

Hopper said that’s “completely unscientific.”

Memories, especially traumatic ones, can be encoded in the brain but not accessible to you, Hopper said. Getting to them is a matter of context and cues.

“Just because something is stored in memory, doesn’t mean that it’s going to be retrieved at any particular time or during any particular time period,” Hopper said.

That means Schatz could have left details out of her first interview with MSU police because, either she wasn’t in a comfortable setting to share them, or her brain had blocked them out until a context or cue triggered her to remember them, Hopper said.

Schatz said the first statement to police was the first time she had ever talked through the entirety of what happened. So it “makes sense” that the later statements – taken after she had talked about the experience with her therapist and friends – would be more complete.

Remembering more of a traumatic event as time goes on is a well studied phenomenon, Hopper said. It even has its own scientific name: reminiscence.

“This resolution officer says ‘oh you remembered more, well you must be lying, and making it up, how convenient that you remember more,’” Hopper said. “When it could just be a totally normal, natural thing of ‘hey, you remember more later because you’re less stressed and you’re asked better questions that remind you.’”

Lilley Schatz, 22, of East Lansing, inside her apartment on Dec. 7, 2023. After being sexually assaulted in September of 2022, Schatz has been on a journey to heal her trauma, not only from the assault, but from the exhaustive process of trying to find resolution within law enforcement and the university.

In other places, Galanos said Schatz wasn’t believable because she flipped the order of certain events.

Hopper said that is also an unscientific conclusion, because the brain is often unable to encode the order of specific events during periods of high stress, like a sexual assault.

He said that for the first few minutes of a high-stress event, the brain’s “defense circuitry” kicks in and it may be able to encode even more information than before. But, research has shown that’s “unsustainable.”

The brain often eventually loses the capacity to store information like the order of events that is not necessary in the moment.

That can leave a survivor of something traumatic, like Schatz, without a clear idea of what happened when.

“It’s not just about sexual assault,” Hopper said. “We see this in police, we see this in soldiers, it’s just how things work. There’s no basis for assuming that someone lacks credibility because they mix up the sequence of traumatic things.”

Galanos also faulted Schatz for saying the guns were brought up on a FaceTime call in one interview with investigators and that they were brought up in-person in another. The statements were made eight months apart.

Hopper said that, again, doesn’t seem informed by the science of how trauma can affect the brain.

Overall, Hopper said Galanos’ decision shows the MSU police and OIE using multiple interview, investigation and analysis tactics that aren’t informed by the science of trauma and memory.

“It’s the incompetence of the investigators that often create these inconsistencies, which then get weaponized against the victim,” Hopper said.

In her decision, Galanos acknowledges in multiple places that “the passage of time and fact that (Schatz) provided statements at several different points may” explain the discrepancies.

But nonetheless, Galanos concludes that Schatz’s “confusion and the fact that significant portions of (her) factual account have changed over time impacts the reliability of claimant’s recitation of the facts.”

With that in mind, Galanos writes that the allegations outlined by Schatz are “more likely than not” false.

Galanos did not return messages seeking comment. MSU declined to answer questions about the decision and tactics used, citing student privacy concerns.

Schatz said Galanos’ decision left her blaming herself. It felt less like a test of the facts of the case, she said, and more like a test of her performance with investigators and at the hearing.

“It was frustrating, it made me feel like if I would have ‘done better’ or if I would have said certain things that I didn’t, this would be different,” Schatz said.

Schatz also took issue with Galanos concluding that she and the football player were “equally unreliable” witnesses.

Galanos said Schatz provided an “inconsistent factual account” and the player provided an “insufficiently detailed factual account.”

After reading that, Schatz felt she was punished for cooperating most fully – providing multiple statements over the months of investigation and attending the hearing where she would be cross-examined – while the football player was rewarded for refusing to participate whatsoever.

In the weeks after the decision was issued, Schatz felt the denial and doubt that had once plagued her return.

“I went into a denial, like maybe it wasn’t as bad as people were telling me,” Schatz said. “I knew it happened, but I was like, maybe it wasn’t important.”

Schatz asked her OIE advocate about appealing the decision, which would send the case to another resolution officer who would determine if the findings were “arbitrary and capricious.”

Her advocate told her “appeals never win” but she was determined.

“They’re like, ‘I don’t want to deter you, but you’re never going to win an appeal,’” Schatz said. “Then I did it anyway.”

She filed an appeal arguing that Galanos’ conclusion was “unreasonable” because the inconsistencies cited were due to “factors outside of (her) control” like the passage of time between her statements and the effects of trauma on the brain.

The MSU Equity Review Officer who decided the appeal concluded that Schatz “understandably disagrees” with Galanos’ decision, but the reasons cited were “not sufficient that a finding is arbitrary or capricious.”

That final appeal decision was issued Sept. 11, 2023. That's 361 days after she was assaulted and 359 days after it was first reported to the OIE.

The assault happened at the very start of her fall semester, the hearing just after finals in the spring, and ultimate decision just as classes began the next fall. The case occupied “a whole year of (her) life,” Schatz said.

That timeline made the result all the more frustrating for Schatz, who said that having to revisit the traumatic events over and over again across the long investigation “stunted her healing.”

“I definitely wouldn’t recommend it,” Schatz said. “It’s just not a great process, and it doesn't happen very quickly.”

At the start of the investigation, she felt “taken seriously” and supported by the OIE. She felt reporting was the right thing to do.

But that faded, and today, she’s not sure if she would encourage another survivor to report their assault to MSU.

“If it would have been the way they said it would have gone, I think I would feel more ready to advocate for people to do it,” she said.

A plea to athletics

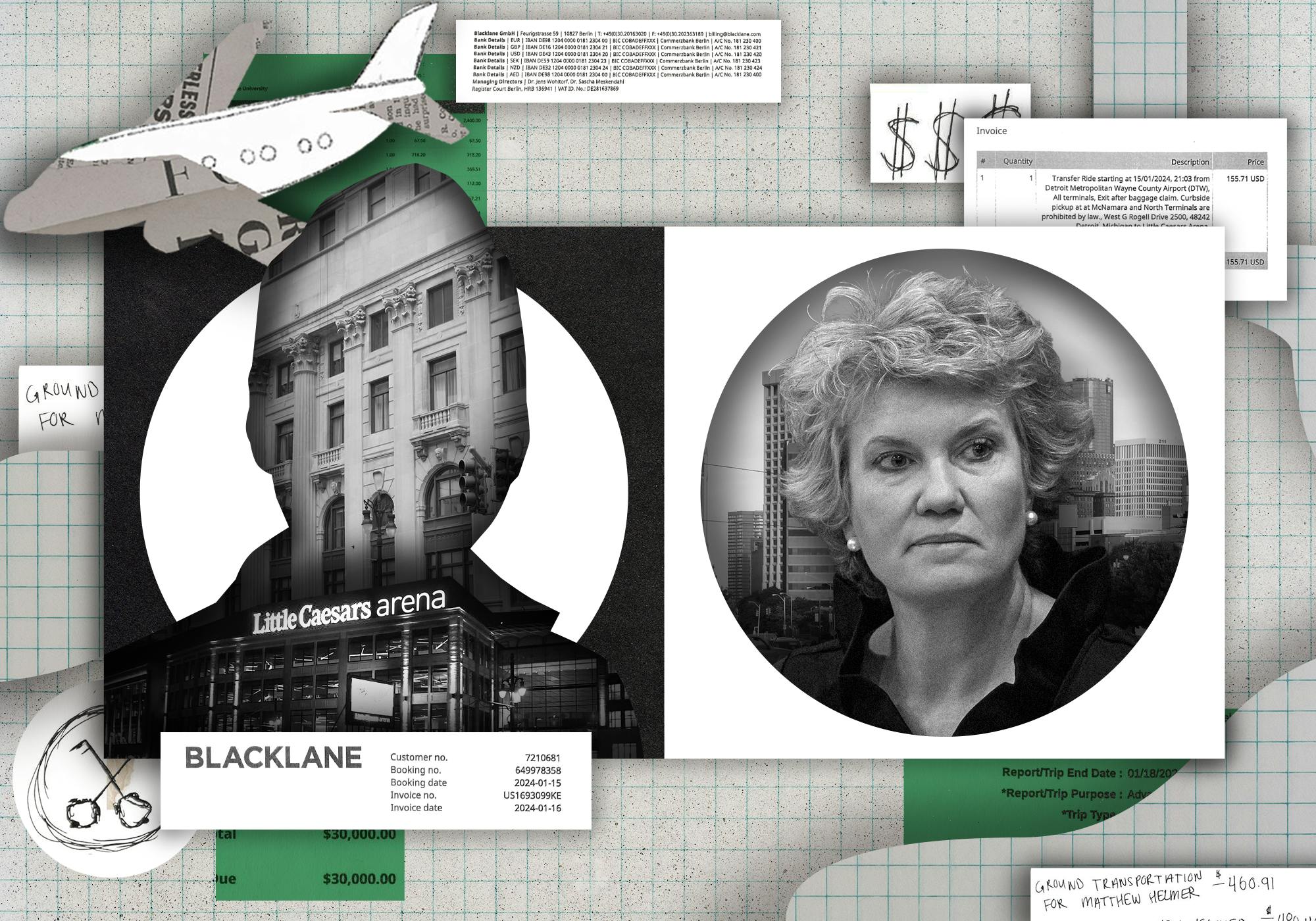

MSU’s athletic director, Alan Haller, was one of the first people to know about the allegations against the player.

He was contacted by MSU police on Sept. 19, 2022, just before the player was first interviewed by police.

In that interview, the detective asked the player if he had any questions about what would happen next, according to the detective’s notes.

The conversation quickly addressed the player’s status on the team. The detective said he wasn’t sure how the athletic department would react to the allegations.

Then, according to the notes, “(the player) stated: ‘I’m suspended.’”

It’s unclear if he ever was suspended.

The State News could not find a record of the player being suspended at any point in the 2022 season. He played in almost every game in 2022.

Haller, through a spokesperson, declined to comment.

Inside of 1855 Place on Harrison Road in East Lansing on Dec. 7, 2023. 1855 Place is home to the MSU Athletics Department offices.

As the football season wore on, healing became harder for Schatz.

For the first month after the assault, she was too anxious to attend classes, her roommate told the OIE.

The player knew where Schatz lived, and she was in constant fear of encountering him, her roommate said.

The anxiety worsened when she faced reminders of him.

Schatz and her friends eventually tried going to football games, as they had done before. But she couldn’t get through the game, she had a panic attack and left.

“She was shocked to see him playing and in uniform after the athletic department was made aware of the incident,” her roommate told the OIE. “She felt like no one believed her, and she fell into a deeper depression.”

Schatz was still feeling the effects of what happened daily, all while she saw him gaining playing-time and notoriety.

“I was crying every day, I couldn’t leave my apartment, I couldn’t take my dog out, I was dealing with police officers, I was getting a rape kit where they swabbed every part of my body, and he’s just living his best life playing every weekend,” she said.

She wanted action from the athletic department, but suspected that they would say nothing could be done until the OIE and MSU police investigations were complete.

Then, in October 2022, members of MSU’s football team were suspended pending an investigation into their fight with University of Michigan football players in the tunnel after the rivalry matchup.

Schatz wondered: if they could be suspended during an investigation for physical assault, why couldn’t he be suspended during an investigation of sexual assault?

She wanted an explanation, she “really just wanted to talk to Mel Tucker” about what his player did.

Tucker was then the head football coach. He has since been fired and found by MSU to have sexually harassed a team vendor.

Schatz didn’t know how to get in touch with him, so her EVE advocate, from the hospital, “called and called and called” MSU athletics until someone gave her an email address that would supposedly go right to Tucker.

Schatz sent an email which details her allegations, then asks why the athletic department declined to take action over them.

She asked Tucker why the player couldn’t be suspended for what he did to her until a formal finding or criminal charges, when Tucker’s other players could be suspended for what they did in the tunnel before findings or charges?

“Is sexual assault not as important as physical assault?” she wrote in the email. “This event happened two months ago, two months I kept telling myself that at one point you would take it seriously, but you never did.”

She never got a response.

It’s unclear if Tucker ever saw the email. OIE documents show it was shared and read by other high-level athletics staffers.

The address Schatz emailed was checked by an office assistant in the football department, Cynthia Mejorado.

When she saw the email, Mejorado did two things: she filed a report with the OIE, and shared the email with her boss, general manager of football operations Saeed Khalif, according to OIE documents.

Khalif then printed out a copy of the email, put a sticky-note on it saying “from Saeed Khalif” and placed it on Haller’s desk, according to OIE documents which include a photo of the printed email on Haller’s desk.

Haller, the athletic director, then filed an OIE report of his own.

Another staffer in the football department also filed a report with OIE based on Schatz’s email, though they left their name and title blank on the report.

When Schatz got the evidence packet for her OIE case – which included all the reports – she was shocked by how widely her email was shared and read.

Lilley Schatz, 22, of East Lansing, stands outside of the gates of Spartan Stadium on Dec. 7, 2023. Schatz transferred from Lansing Community College in the Fall of 2022 eager to experience the renowned East Lansing game days and football culture. After being sexually assaulted in September of 2022, she was unable to attend football games for the rest of the 2022 season and the following 2023 season. “I had to continue to go to every single class, continue to do well in school, I had to do so much,” Schatz said. “I had to get a rape kit, I had to go to the hospital, I was there all night, I had to meet with an advocate twice a week, I have to meet with a therapist once or twice a week. All he has to do is play football every weekend.”

She thinks the decision not to suspend the player “is wrong.” Seeing all the people who read the email and never reached out to her with an explanation “shows (her) that they know it’s wrong too.”

A few weeks after the impassioned email, the 2022 football season ended. Schatz said things then “started getting better for (her) mentally,” without the constant reminders of what happened.

Then, earlier this fall when football resumed and the player continued to improve his playing-time and notoriety, the anxiety and doubt returned.

A trodden path

Schatz’s experience is strikingly similar to other stories of MSU students who reported sexual assault by high-profile student-athletes to the university.

In 2019, Bailey Kowalski, then a sports-journalism senior, publicly came forward with her story of being raped by members of MSU’s basketball team and then being disbelieved by MSU.

Kowalski said in a lawsuit that when she first disclosed the assault to an MSU counselor, she was discouraged from reporting it.

“If you pursue this, you are going to be swimming with some really big fish,” the counselor told her, according to the lawsuit.

Kowalski’s case was eventually reported to the OIE, which initiated an investigation that would last over a year.

The resolution officer in Kowalski’s case did not find sufficient evidence of wrongdoing by the basketball players. That result was supported by a “credibility assessment” with an uncanny resemblance to Schatz’s case.

Both decisions deem the claimant uncredible by comparing multiple statements and interviews with the claimant taken months apart.

It would be hard to know how many OIE decisions use that “credibility assessment” process.

Schatz, and Kowalski through her attorney, both shared copies of OIE documents with The State News. Those same documents could not be obtained through records requests to the university.

While MSU is subject to public records requests, the university has for years refused to release even heavily-redacted versions of OIE decisions that end in no finding of wrongdoing.

Hopper, the expert who called the assessment “unscientific,” said he wonders how many cases have wrongly ended in no-finding because of it.

“You might want to ask MSU, what is the scientific basis for their resolution officers judging inconsistencies as credibility problems?” Hopper said.

MSU declined to answer any questions about the practice.

Beyond just the “credibility assessment” in OIE decisions, MSU has been heavily criticized in recent years for multiple practices that are said to systematically discredit, ignore or bury reports of sexual assault by high-profile athletes.

A 2018 ESPN Outside The Lines investigation concluded that MSU had largely ignored some allegations of sexual violence by athletes, kept some away from investigators by allowing the athletic department to internally investigate them, or used practices that ensured the most common result of police or university investigations would be no finding of wrongdoing.

For Schatz, the breadth of the issue makes being a survivor all the more confusing.

She knows that she isn’t the only person to go through it – reporting, disbelief, no results – but it’s rare, she said, that someone would talk about it.

“I know this is really common,” she said. “But at the same time, it’s really isolating.”

MSU, through various spokespeople, declined to answer any of The State News’ questions about Schatz’s experience.

Laura Rugless, the university’s new Vice President for Title IX, declined to speak specifically about Schatz’s case, citing privacy concerns, but did issue a written statement to The State News.

She said stories from survivors like Schatz help her “understand the circumstances around their experience and use their feedback to continually enhance (MSU’s) processes.”

“We recognize the bravery it takes for individuals to share concerns, and we want them to know their voices are not just heard but genuinely valued,” Rugless said in the statement.

Schatz said Rugless’ statement shows that survivors at MSU are “in a situation where they have to go to a newspaper to get help and have their voices heard, cause their voices aren’t going to be heard any other way.”

“My story shouldn’t have to inspire change for other people,” Schatz said. “It’s kind of messed up that my case has to be handled so wrong for them to look at what they’re doing.”