| Content warning: This article contains descriptions of sexual violence. The National Sexual Assault Hotline can be reached at 800-656-HOPE (4673). |

David Batterson now knows that he was repeatedly raped and molested by ex-MSU doctor Larry Nassar during years of medical appointments beginning when he was 10. But for much of his life, he wasn’t sure.

He knew he felt uncomfortable leaving the appointments, that his body was “breaking down” as he lost interest in the sports he once enjoyed, but when he raised concerns to friends and family, he was met with doubt and anger, leaving him feeling “ashamed.”

He struggled for years, numbing himself with substance abuse and finding himself unable to maintain healthy relationships.

Finally, in January of 2023, he hit rock bottom and sought help.

Without health insurance he wasn’t sure how he could pay for counseling, so he turned to Michigan State University, hoping the institution that said it was committed to “thoughtfully creating solutions” for those its doctor had hurt would be able to provide him with support.

He was bounced around between MSU’s police department, Center for Survivors and Title IX office before someone told him about the Health and Healing Fund: a $10 million fund dedicated to covering counseling and mental health services for Nassar survivors. It was just the thing he needed.

So he applied, and the next day, he received a to-the-point rejection.

“(An eligible recipient is) a female who received treatment from former doctor Larry Nassar at a MSU health clinic or as a MSU student-athlete,” the fund’s administrator wrote in an email obtained by The State News.

Why would the language exclude male survivors, especially when accounts of Nassar abusing young men were published in national media as early as 2018?

The policy posted by MSU online doesn’t restrict applicants by gender and includes the spouses and parents of survivors. But the university doesn’t handle the screening and vetting of applicants, that’s contracted out to a 3rd-party: Seattle firm JND Legal Administration.

The policy on JND’s online application portal is the same one sent to Batterson, only covering female athletes who received treatment at MSU.

When reached by The State News for comment on the mismatched policies, MSU spokesperson Emily Guerrant said the university would “ensure that gets cleared up.”

“We’ll be making sure that the administrator is aware we do not have a preference or a limitation on sex or gender identity of the patients,” Guerrant said.

After conflicting communications from MSU's various agencies, Batterson has reapplied to the fund. He's been waiting for weeks to hear back, and is hoping for a different result.

“I’ve always been in this weird loop of people trying to bash me because I talk about what happened, everyone thinking I was crazy,” Batterson said. “It feels the same with these JND people.”

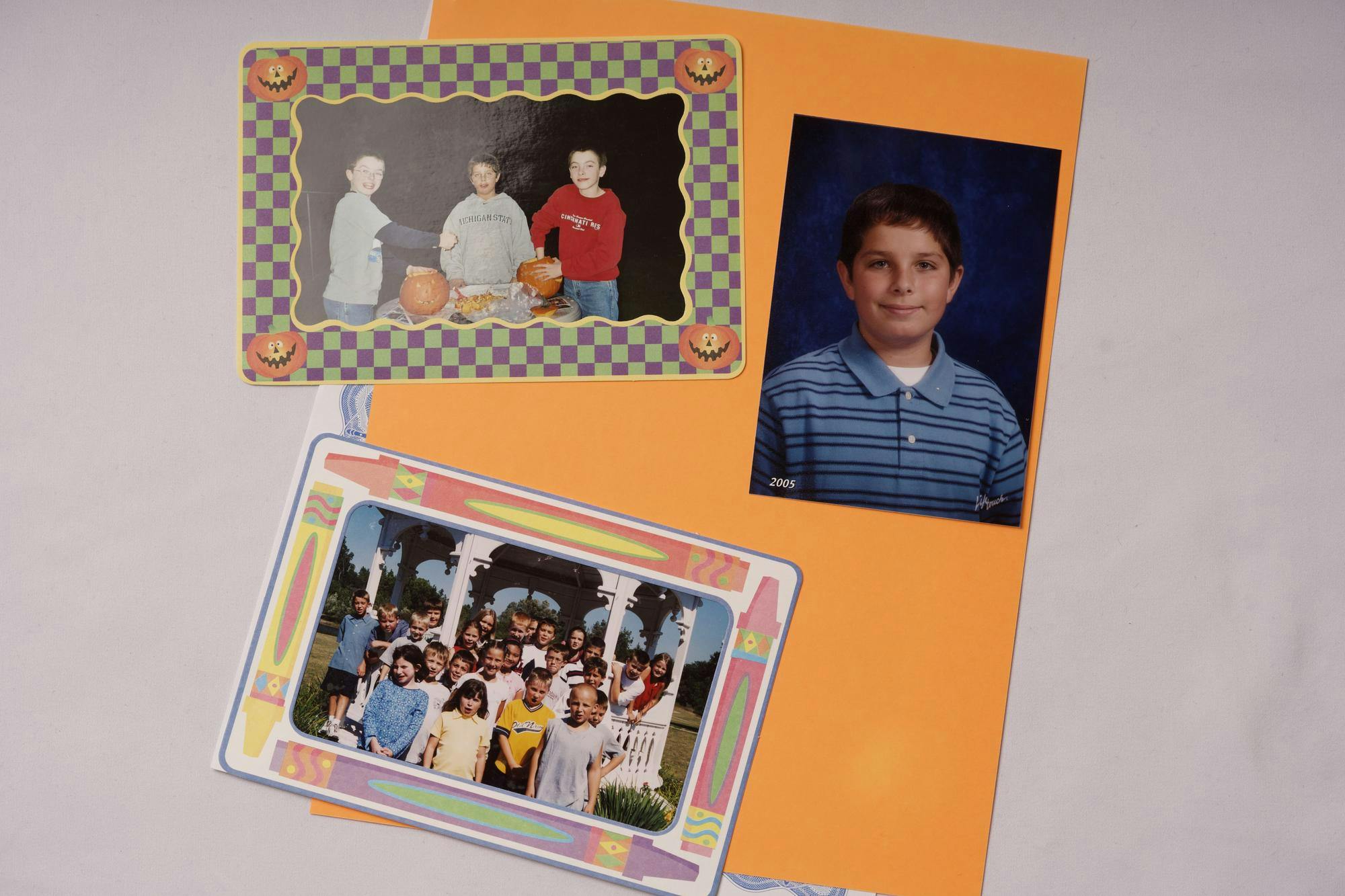

Photos of Batterson at the age when Nassar began abusing him.

Batterson’s journey

Batterson first came into contact with Nassar in August 2005 when his father took him to a clinic for young athletes at Washington Woods Middle School in Holt, Michigan.

Nassar told Batterson he had to check for hernias, but unlike the scientifically-sound hernia tests Batterson would come to learn involve pressure on the inner thigh, this test involved Nassar inserting his fingers into a then 10-year-old Batterson’s rectum.

Over the next two years Nassar repeatedly abused Batterson at clinics and during appointments in MSU’s osteopathic medicine building. A criminal investigator at MSU’s independent police department, MSUPD, would later determine in 2023 when Batterson finally filed a police report, that in all, Batterson was raped and molested 18 times during these sessions.

Batterson describes the abuse as a calculated cycle, with Nassar physically hurting him to create opportunities for sexual acts.

Often this was as simple as Nassar dislocating Batterson’s joints — which were weakened by his Ehlers-Danlos syndromes — so he could initiate “hip-to-hip manipulations,” stretching Batterson across the examination table before sexually assaulting him.

But Nassar’s longest-running con was a set of prescription insoles — one a half-inch taller than the other — which Batterson’ said "destroyed" his back leading to years of pain and physical therapy.

Prescription insoles and custom shoes Batterson wore for years at Nassar's behest.

Nassar insisted that contact sports like football or wrestling would be too hard on Batterson’s joints, so he quit and joined the track and cross-country teams.

This left Batterson running miles every day on the lop-sided insoles, further hurting his back and hips, leading to more appointments with Nassar and more opportunities for abuse.

Nassar’s guidance about acceptable sports and wearing the insoles was strictly enforced by Batterson’s father, a man who was extremely supportive of Nassar.

Batterson says his dad, former MSU Fisheries and Wildlife professor Ted Batterson, was “obsessed” with Nassar, often calling his son “delusional” for complaining about the sessions and “rooting for Nassar” when he was first publicly accused of wrongdoing in 2016.

Today, Batterson says he doesn’t have a relationship with his father. He said when they have talked, his father would say he "had no idea" that anything was going on.

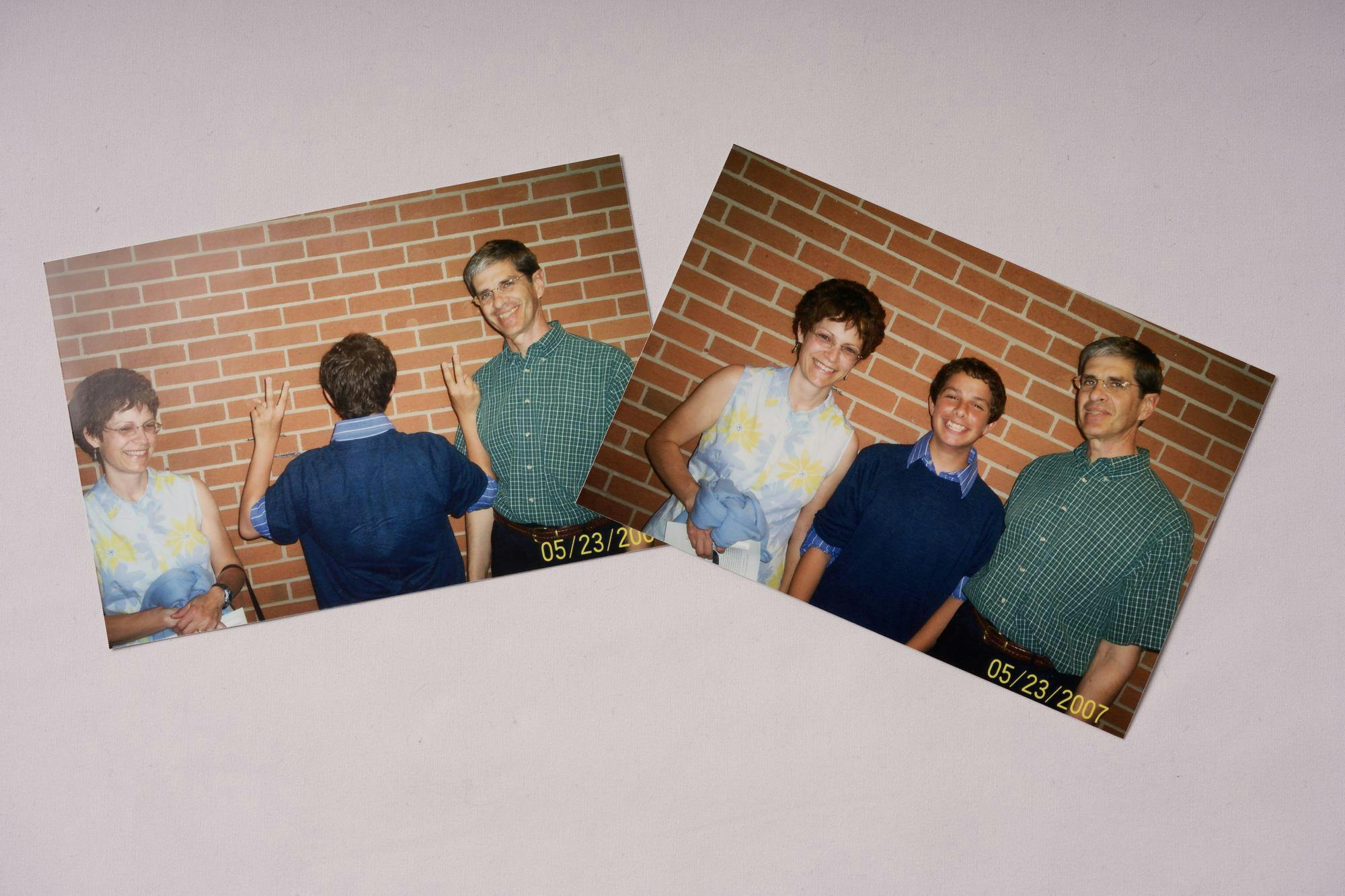

Batterson with his parents in 2007.

Batterson also raised concerns with his brother, telling him he thought he had been molested in 2009. His brother dismissed the concern, calling him a slur for gay men.

His mother wasn’t told about the abuse until after Nassar’s wrongdoing was publicized. When Batterson spoke to her about it, she accused him of making it up in an attempt to make money, referencing the $500 million settlement to survivors.

But it wasn’t just those around him who didn’t believe his tales of abuse. Batterson himself spent years unsure if what was happening to him was wrong.

He grew up broadly ignorant of sexual assault, in a household where “uncomfortable topics” were “swept under the rug,” and he was sheltered from media involving sex or consent. He says this left him unable to understand what was happening to him in the sessions.

“I didn't know anything about what’s rape or what’s molestation,” Batterson said. “I just didn't know about it.”

He was especially confused about what it meant to be a male survivor, feeling ashamed of his abuse.

“I never wanted to be a man who got raped and molested, even though I was 10,” Batterson said.

Various family scrapbooks Batterson revisited when piecing together memories of the abuse in 2023.

Alexis Schneider — a therapist who temporarily treated Batterson pro-bono and spoke to The State News about her patient's condition with his permission — says she believes he spent the last 17 years suppressing what happened to him.

He self-medicated with drugs and alcohol, had a few now-expunged run-ins with the law and found himself unable to have stable relationships.

He said he struggled to trust or love because, “I loved my dad the most, then it was him who threw me to the person who raped and abused me.”

Schneider says he blocked out precise recollection of his sessions with Nassar, with flashbacks to the abuse being occasionally triggered while alone or during sex.

In 2012 Batterson began attending MSU but left the university after running into Nassar on campus. He transferred to Lansing Community College before eventually returning to MSU to complete his degree in kinesiology.

After graduating, he worked as a personal trainer, attempting to develop a method of training that didn’t require any touching, hoping to accommodate survivors like himself who were weary of hands-on training and physical therapy.

But his innovation was not well received, leading him to leave the sports-medicine industry altogether. Today, he works in contracting.

Batterson’s struggles worsened as accusations of Nassar’s misconduct became public. He says he was unable to read accounts of Nassar’s abuse or reporting on MSU’s failure to address it for so long.

In 2018, as Nassar’s sentencing dominated the news, Batterson attempted suicide with an overdose of prescription pills.

He spent the next few years jumping around with seasonal work in various places, before returning to Lansing.

In January, as his drug use increased and his grandmother died, Batterson hit what he believes to be his “rock bottom.”

Before her death, Batterson’s grandmother had told him that she was sexually abused as a child too and that she “wanted him to be free.” With that in mind, he sought mental health services.

He got in touch with MSU’s Center for Survivors, but they only provide services to current students. Then he went to MSUPD to file a criminal complaint, hoping that would make more resources available. The department told him he should reach out to the Office of Institutional Equity, the MSU office responsible for investigation and discipline relating to Title IX violations outside of the criminal legal system.

So Batterson talked to Nicole Schmidtke, MSU’s Title IX coordinator, who told him about the JND support fund.

“If you feel comfortable, I would love to hear back that you were successful in getting access to the fund,” she wrote in an email obtained by The State News.

Two weeks later, Schmidtke — who Batterson describes as the only MSU official who has “gone to bat for him” — checked back in to make sure he got access. He replied informing her that he was denied because the fund didn’t include male survivors.

On May 12, she told him that she “made some calls” in hopes of changing that restriction and that she wanted him to try re-applying altogether in hopes of a different result.

As of June 1, he has not heard back from JND.

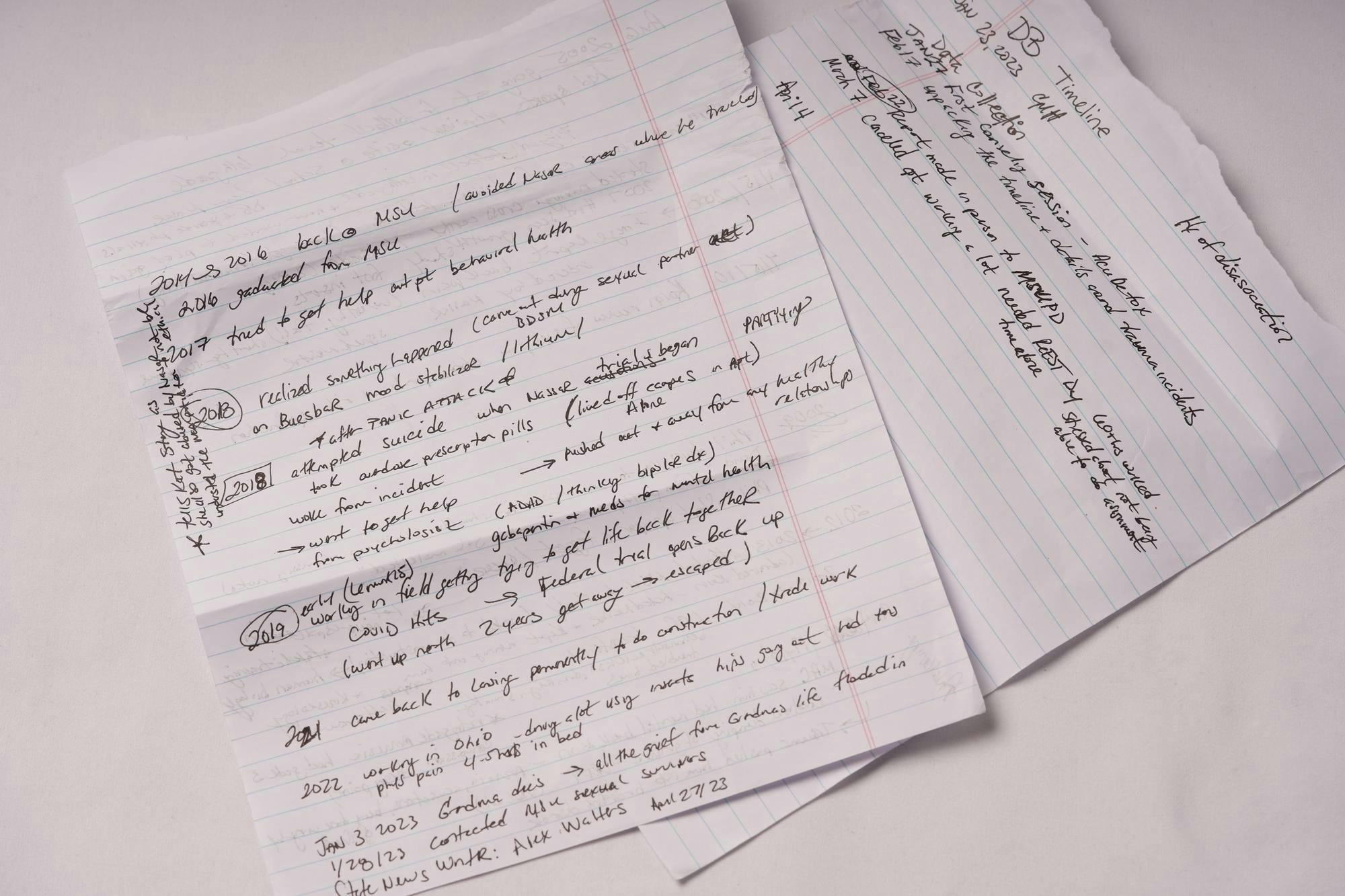

Hand-written timelines Batterson assembled to make sense of the abuse in 2023.

Work for change

JND isn’t the first firm to administer the fund.

It was initially run by Boston mediation firm Commonwealth, until over $500,000 in fraudulent claims were made, leading to a year-long freeze of the fund and a change of hands. Then it was run by Kansas insurer New Directions Behavioral Health, before JND most recently took control.

Valarie Von Frank, president of the survivor advocacy group POSSE, said despite the access issues, JND has been far more responsive to concerns of survivors than the previous administrators.

“It’s been night and day ... they're the best advocates for survivors,” she said, comparing JND to New Directions.

But she believes there is still more work to be done.

MSU and JND have recently agreed to regular meetings with a committee of survivor advocates to discuss ways to improve the fund.

The committee, composed of Von Frank, survivor parent Lynne Erickson and survivor Danielle Moore, hopes to expand coverage to not just male survivors, but to also allow for family therapy and counseling for children of survivors, Von Frank said.