Editor’s note — The subjects in this article might be sensitive for some readers.

Ending the cycle: The reality of homelessness and how the community can help

If Terri was born 37 minutes earlier, everything might have been different.

If she was born 37 minutes earlier, she would have been born on Dec. 14 and would have graduated at age 17. But she was born on the wrong side of midnight and on Dec. 15, the day after the cutoff date for kindergarten admissions in her school district.

One of Terri’s earliest memories is of her fifth birthday. For most, birthdays are a celebration of another year lived. For Terri — who was granted anonymity for her safety — they were a countdown. She remembers her mother mouthing “thirteen” to her so her father wouldn’t see. Thirteen was how many years it would be until she was 18 and legally old enough to live alone.

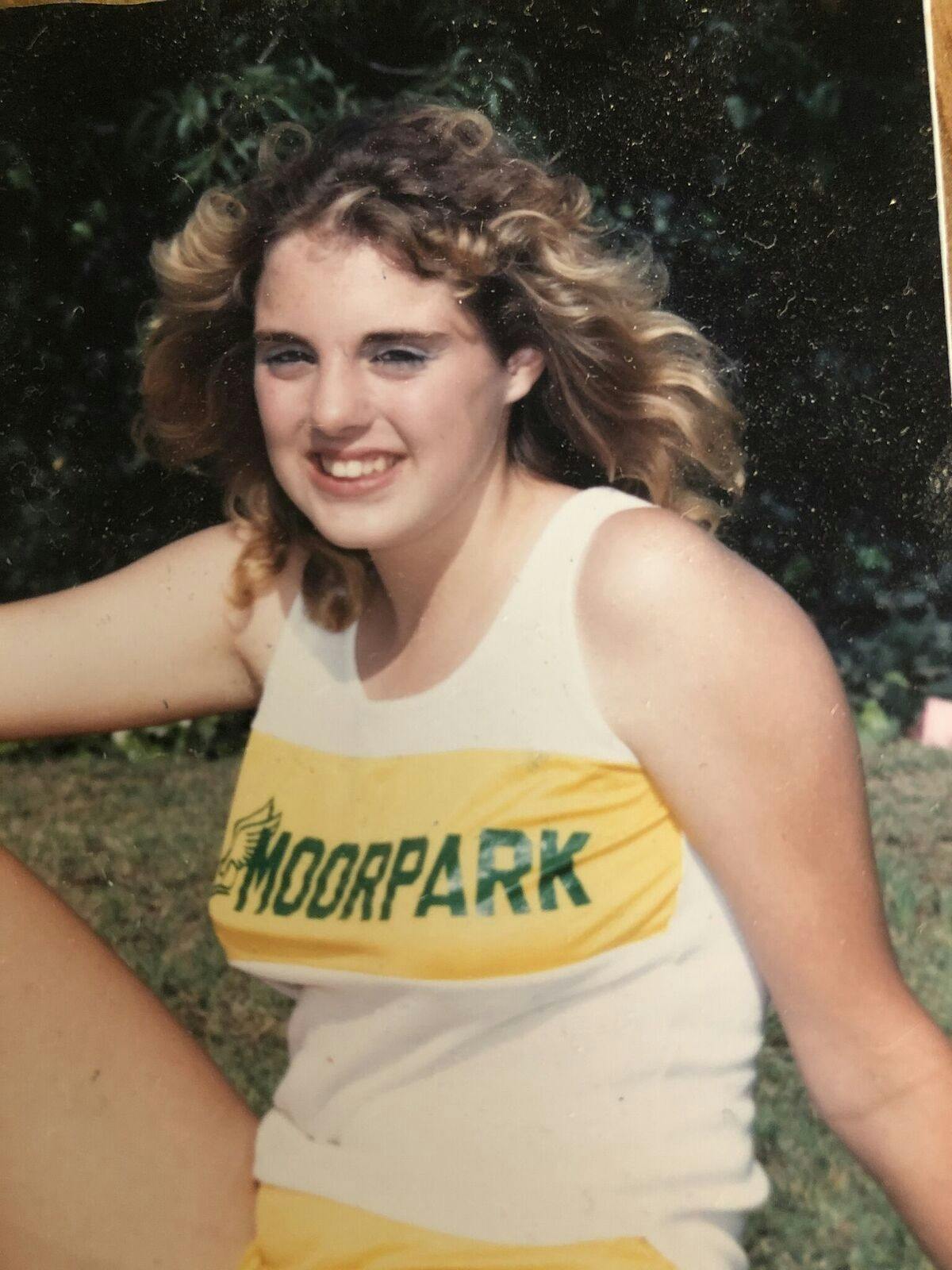

Despite the challenges she faced at home, Terri said she remained positive. When she started high school, her family moved from Rochester, Michigan to Moorpark, California. She was a leader of the marching band, dazzling with flag routines.

Terri worked hard in class and was on pace to graduate. Her dream was to be a kindergarten teacher.

However, a few months before graduation, Terri broke her arm in a car accident. Unable to grip a pencil, she would go to the computer lab after lectures to type in-class assignments. One teacher gave her an unexcused absence every day and she had to take Saturday classes as a result.

Terri’s mother used this as a reason to kick her out of the house. Three weeks before her senior exams, she was homeless for the first time.

Terri stayed with a friend who lived 18 miles from her school for a while. After being accepted to three colleges, she said she flunked out of high school because she couldn’t find a way to get to class during her last few weeks.

From there, Terri’s downward spiral accelerated. She followed a band to stay with the members, she’d sleep in the car her father gave her shortly after she would have graduated. Eventually, she started staying with Mark. He was someone she considered to be a friend, even though he made unwanted advances toward her.

“I didn’t want to do a lot of the things that I did,” Terri said. “I just thought that helped me stay longer in his house.”

After leaving Mark’s, Terri had a stint where she stayed with a friend before moving back to Michigan. Altogether, she spent three months homeless in California.

READ MORE

Terri said her life continued to go downhill after she returned to Michigan.

She was married for less than a year to an abusive husband. She worked three jobs at once during the marriage, but didn’t make a dime — he took everything from their joint account.

Despite the tumultuous circumstances, Terri continued to chase her dream of teaching kindergarten. She received her high school diploma in 1993 from Clintondale Community Schools, four years after she would have graduated.

Terri gave birth to her first son, Ken, at 23. She and Ken’s father, Harvey, had their second son, Mitch, in 1997. Terri spent portions of her time as a young mother bouncing around.

She would stay in her car, with friends or with family. Twice, she lost nearly everything when it was stolen from a shelter she stayed at.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Terri racked up six evictions, making it nearly impossible to find a decent living situation. She said her landlords seemed to look for any reason to evict her and her children, and they were often forced to live in dirty spaces with broken appliances.

Her unstable housing situation forced her to lower her expectations of what a healthy relationship should look like. Physical, sexual and psychological abuse became routine.

Every time she met a guy, it seemed like the cycle was broken. They all started charming and kind and became abusive as time passed.

Terri thought she found something new when she met someone in February of 1997.

The two met when the kids were staying with Harvey for the night and Terri took a rare trip to a bar. He sparked a conversation, and they became close over the next few months. Terri liked that he was taking things slow. They got to know each other for more than a month before they started dating seriously, and things were so easy with him that Terri could focus on raising her kids without the regular pressures of a relationship.

Terri said she trusted him. He was a hard worker and wanted a traditional family. Her kids adored him and her family approved of him. He was well-respected in the community.

Which is why Terri said she was surprised when he abused her for the first time.

The couple had gone to a karaoke bar about half a year into the relationship. He declined when Terri asked him to sing a duet with her, so she asked the man running the karaoke night and he accepted.

He and Terri stayed at her friend’s house for the night. When they got back, Terri said he screamed at her and overturned all the furniture in the room. She said he told her singing karaoke with the other man was unfaithful, and called her the name of an ex-girlfriend who had cheated on him.

He charged toward Terri, and she fled downstairs and hid in a closet. Eventually, her friend’s wife was able to calm him down. Terri considered leaving the relationship that night, but abuse had become so embedded in her makeup, so she stayed.

“I still hadn’t broken that abuse cycle,” Terri said. “So I understood it.”

The next day, Terri said he cried when he apologized. He swore to never mistreat Terri again — a promise she said he broke two months later. The abuse became increasingly frequent as time went on.

Terri tried her best to keep the boys happy and shield them from their hectic surroundings.

Terri and the boys spent two summers “camping” because she couldn’t find a better place to stay. Mitch said he was 20 years old when he found out they weren’t on vacation.

“I made sure that (Ken and Mitch) had a smile at least three or four times every day, but that (they) also had a laugh,” Terri said. “A hard, make-you-beg-and-plead-for-mercy-for-the-laughing-to-stop kind of laugh. I made sure that happened every day.”

They lived in commercial housing when she said the man she was involved with tried to kill her.

He stumbled over to Terri, who was lying in bed. She said she knew he was standing over her, but she pretended to be sleeping.

Suddenly, Terri felt the cold cylinder of a rifle pressed up against her head and heard him crying. She didn’t resist or even move. She just listened to Ken and Mitch breathe for what she thought would be the last time.

“Click.” Nothing happened. He pulled the trigger again with the same result. Frustrated, he stumbled outside.

A few moments later, Terri heard the rifle go off.

She took her sons and hid under dirty clothes tucked behind a dresser for the rest of the night. She’d find out later he threw the rifle in the woods behind the house and it exploded.

Threatening her life wasn’t enough to drive Terri from the relationship. For the first time in her children’s lives, they had someone to call “Dad.” Even if it meant she had to risk her own life, she said she couldn’t take that from them.

For two years after that, Terri stayed with him before she became fed up and was finally ready to leave. When she told him, she said he told her if she left he’d track her and the boys down and kill them. In October 2002, Terri said she and her sons tried to leave. They took off in the family car with every intention to never come back.

However, when Terri tried to hit the brakes at a stop, nothing happened. They got into a five-car collision, which Terri was hospitalized for. Ken and Mitch were unhurt.

The hospital called Terri’s emergency contact, the man she was involved with, and his sister came to pick her and the boys up and take them back to him. Terri was caught in the cycle of abuse once again.

She was taking classes at Baker College and about a month after the accident, read a children’s book about “good touch” and “bad touch” to Ken for an assignment. After listening for a while, Ken told Terri he knew about the bad touch. He told her the man she was involved with had touched him in the bad way.

Terri’s heart broke. She felt she failed Ken. She knew they had to leave. Five long days after Ken told Terri about the abuse, the man was out partying and there was a window to escape.

Mitch said he remembers the family packing everything they could in 15 minutes and fleeing from him for good.

The reality of homelessness looks a lot like what Terri experienced — people placed in a bad situation doing everything they can to make ends meet.

Homelessness isn’t always continuous, as people often weave in and out of having shelter. Terri’s credit report shows 37 addresses. It could be more.

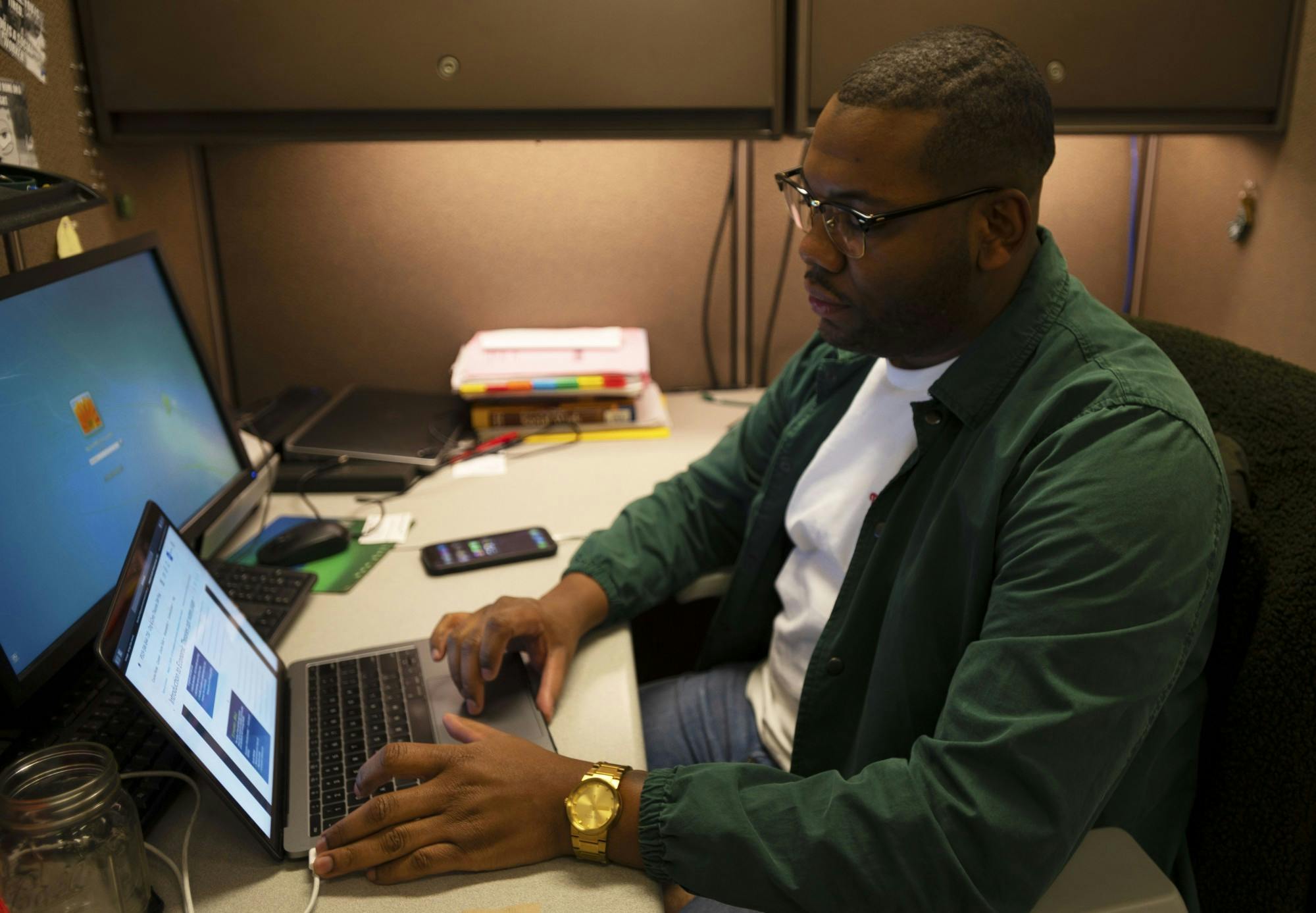

Michigan State graduate student Bezil Taylor is dedicated to making sure as little people as possible have the same experiences with homelessness as Terri. He is a student in MSU’s Department of Sociology and studies youth and young adult homelessness.

Terri didn’t make it to a college campus before she became homeless, perhaps things would have been different if she had. But homelessness could have very well followed her to school, as it does for many around the nation every year.

In fact, homelessness affected 14% of respondents who attended four-year institutions, according to a survey of nearly 86,000 students taken by The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice.

“The thought process is: If home is not as stable as we’d like it to be or the greatest situation, once a student gets to college — they’re all set,” Taylor said. “That’s not actually the reality.”

Taylor said homelessness on college campuses can look different than in other places, and that students staying on friends’ couches is a common example. He said the feeling of being a burden or not knowing how long you can stay can take a toll on student’s mental state.

“(Sleeping on someone’s couch) may sound better than sleeping in a car or sleeping in a shelter, but sometimes that can be just as traumatic,” Taylor said. Taylor said the financial aid colleges give is often not enough, and if it is, students have to use their refund checks to help out family. He said he’s seen students have to spend that money on sick family members and health insurance.

There are a lot of communities that don’t have quality services for their homeless population, Taylor said. East Lansing is not one of those communities — especially when it comes to the services available to MSU students.

With programs like Fostering Academics, Mentoring Excellence, TRIO Student Support Services, the Student Parent Resource Center and the MSU Student Food Bank, plenty are here to help.

With programs like Fostering Academics, Mentoring Excellence, TRIO Student Support Services, the Student Parent Resource Center and the MSU Student Food Bank, plenty are here to help.

While all of these programs don’t directly address homelessness, they provide assets that free up money for students at risk of becoming homeless and work to assist home insecure students find homes.

The Student Parent Resource Center helps MSU students who are parents get to graduation. Depending on need, they provide housing, financial and food support among other things.

Center director, Kimberly Steed-Page, believes homelessness at MSU is an overlooked problem.

“I believe that there are more homeless and housing insecure students on this campus than most people would think,” Steed-Page said.

The MSU Student Food Bank does giveaways every Wednesday and hands out essential goods, like hygiene products and cleaning supplies in addition to food. Executive Director Nicole Edmonds said at their most recent giveaway, which was strictly produce, they handed out about 3,000 pounds of produce in an hour and a half. She said they’re seeing more and more people rely on the food bank, with 9,000 to 10,000 visits expected this year.

Edmonds said all kinds of MSU students depend on them.

“There isn’t one specific demographic of student who’s coming to use our service,” Edmonds said. “It’s undergrads, it’s domestic undergrads, it’s international undergrads, international graduate students, Ph.D. students, visitings scholars from all over the world.”

Edmonds said she’s trying to work with the university to develop an app that would alert students of leftover food that would otherwise be thrown out at cafeterias and conferences. Students could then go to the locations and pick up the food for free.

Taylor said he’d like to see MSU work together with these programs. He also said he’d like to see employees working with struggling students to get to the root of their struggle.

“No student has academic issues just because they don’t want to do well in school,” Taylor said.

Taylor said that there could be advisors or other faculty speaking with students on academic probation about the challenges they’re facing in their lives.

“The university should be rooted in support first,” Taylor said.

College isn’t an option for many young adults. Whether they are like Terri and robbed of the opportunity or choose to go another route, they don’t have access to the same resources as college students.

In the Greater Lansing area, nonprofits like “Punks With Lunch” are there for support.

The organization gives out food, clothing and other essential goods to people with unstable housing.

Staffers of Punks With Lunch form close bonds with many of the people they help and have seen up-close some of the hurdles preventing people from climbing out of homelessness.

“To make these phone calls, to get to the appointments, to do all the things you have to do (to escape homelessness) — it’s very difficult and sometimes you have to start back over at square one over and over again,” Punks With Lunch co-founder Julia Miller said.

Haven House is a homeless shelter for families in East Lansing that works closely with its occupants to put them in the best possible position going forward — whether it’s a job, financial plan or simply more time needed.

Haven House Executive Director Gabriel Biber said they find positive destinations for about 60% of those who go through the shelter. Biber said a positive destination is a stable housing situation, whether that’s staying with a relative, a roommate or a place of their own.

However, Haven House typically deals with families who aren’t experiencing chronic homelessness, he said. This means they need less help to break the cycle or avoid it completely. Statewide, only 18% of shelter occupants leave a shelter to a positive destination.

Biber said people with unstable housing are given more hurdles to navigate while finding housing as their situation worsens. He said after an eviction, it’s much more difficult to find someone to rent to you. He said evictions lead to problems outside of housing.

“If you got evicted, it’s very likely you may have had trouble showing up to work on time or fulfilling all your job duties, so you may have lost your job,” Biber said.

One or even two low-paying jobs aren’t enough to pay rent in most areas. Combine that with a few evictions, and people with unstable housing can be pushed to shelters or to rent in places with questionable landlord practices and lack of regulation.

“The landlord, rather than spend the money to (fix things) might rather say, ‘I’m kicking you out’ and try to find another tenant who is not going to push them to do those improvements and repairs,” Biber said.

Biber said his time working with the homeless has opened his eyes to what people in desperate situations will do to put a roof over their head. He said he’s heard many stories about “survival sex,” where women will have sexual relations with men in order to stay in their homes.

“In general, any homeless person is going to likely find themselves in a situation where they’re asked to make some kind of concession,” Biber said.

Being homeless cuts deeper than the simple concept of shelter. Per the Family and Youth Services Bureau, 80% of homeless mothers with children have experienced domestic violence.

Studies have shown between a quarter and a third of women end up homeless due to violence and that homeless women are between two and four times more likely to experience violence.

Ninety-three percent of homeless mothers experienced at least one traumatic event growing up and over 80% experienced multiple. Seventy percent reported trauma that was related to violence from a family member and about half had been sexually assaulted.

As Terri found out, being homeless is so much more than the absence of a roof.

Things didn’t get better right away after leaving the man she was involved with. Terri said she had a lawsuit stemming from the car accident that resulted from her brake lines being cut and had to pay $10,000. She continued to face unstable housing and homelessness. Terri said she reported the man to the police after leaving, and he was eventually sentenced to 15 years in prison — a sentence that expired in 2018.

In January 2020, his court-ordered supervision will be up and he won’t be tracked by a GPS monitor anymore. Terri said she’s afraid that once unwatched, he’ll make good on his promise to kill her and her children.

Terri never got to be a kindergarten teacher. She said years of domestic violence caused extensive nerve damage that keeps her from being able to bend over. She wouldn’t want to be a kindergarten teacher who is unable to speak with a child at their own level.

She’s a different kind of teacher now, an advocate. Terri travels around Michigan speaking, sometimes in front of hundreds of people, about the realities of homelessness, domestic violence and other forms of abuse.

Terri won her battle with homelessness. She’s lived in the same house for over a decade now. She said Ken and Mitch are both happy and functioning as young adults.

Terri smiles when she talks and laughs often. It took over a decade, but she’s accepted that what happened to Ken wasn’t her fault.

Mostly, Terri’s glad her children finished adolescence in a stable environment with the support she didn’t have.

“If I didn’t have my ma,” Mitch said, “then I don’t know what would have happened as a kid.”