During the early hours of May 14, 2016 34-year-old Joshua Christopher Misiak was shot multiple times. The clue to finding a suspect would lead to an MSU research team, a set of fingerprints and a smartphone.

Misiak was driving his brother’s vehicle when he and an unidentified 22-year-old woman were shot near the intersection of Kendon Drive and Wildwood Avenue in Lansing.

Misiak was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Police said another vehicle pulled up and began shooting shortly after 1 a.m. A witness told local CBS affiliate WLNS that he saw the vehicle speed away after the shooting ended.

Investigators said they believe the shooting was intentional and that Misiak and the suspect might have known each other.

Lansing Police‘s public information officer Robert Merritt said Misiak owned a Samsung Galaxy S6. Discovering a possible suspect behind Misiak’s death would involve looking into that smartphone. Unfortunately for Lansing Police, that smartphone was fingerprint-locked, and they didn’t have the resources to try to unlock it.

What they did have, however, were copies of Misiak’s fingerprints on record from previous arrests.

So they turned the phone over to the MSU Police Department’s Digital Forensics and Cyber Crime Unit with the hope that someone there would know how to bypass the specially encrypted lock using only copies of Misiak’s fingerprints. Detective Andrew Rathbun was put in charge of the case, but even he was stumped.

Rathbun said he had no idea how to unlock the phone with the forensics software readily available to him. He contacted third party vendors and other research labs to see if they could do something, but they said it couldn’t be done because the technology needed didn’t exist.

After a week without progress, Rathbun began researching “fingerprint spoofing" online. One of the first links that showed up on Google was the work of Anil K. Jain.

Coincidentally, Jain is a university distinguished professor in the MSU Department of Computer Science and Engineering. On Feb. 19, he and postdoctoral research fellow Kai Cao published a report about using 2-D fingerprint images to hack into smartphones.

“I was just Googling and looking up the results, and there happened to be a research paper,” Rathbun said. “I read it and then I finally saw who it was: Michigan State University. And that was my ‘aha’ moment.”

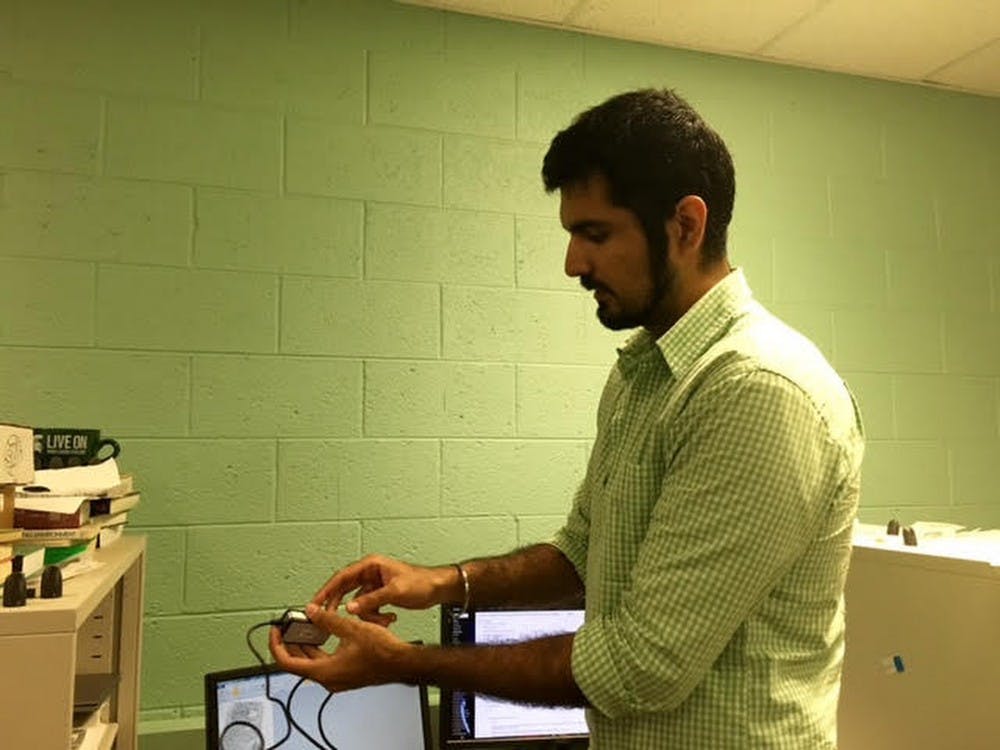

On June 17, Rathbun and another detective reached out to Jain and asked if he could unlock Misiak’s phone without explaining details of his death. Jain accepted the challenge and teamed up with Cao and Sunpreet Arora, a doctoral student from India who specializes in creating 3-D printed fingerprint replicas. None of them had ever been approached by police to help solve a case until Rathbun contacted Jain.

“This is not my first time working with police, but the first time in terms of solving a case and doing operational work for them,” Jain said.

The team of researchers first experimented with printing copies of Misiak’s digits on conductive paper. When that didn’t work, they created 3-D replicas of Misiak’s fingertips using a very small coating of silver and copper to make them conductive. Like the two metals, living human skin is conductive, meaning it can create electrical currents through touch. Fingerprint-locked sensors on smartphones read these currents as images.

Their second plan didn’t work, either.

Jain then realized that the quality of Misiak’s fingerprint images was not good enough for the team to properly replicate them.

Cao had done some previous work in enhancing fingerprint images to improve their quality when he was a doctoral student and professor in China, so he applied his expertise to this case by creating an image enhancement algorithm to fill in the broken ridges and valleys. By doing so, the research team was able to create a more precise image of Misiak’s fingerprints.

They copied and printed replicas of all 10 of Misiak’s digits onto glossy photographic paper.The tools used by the researchers can be obtained at a typical office supply store.

Following police protocol, Rathbun only provided the research team access to Misiak’s phone whenever they were ready to try to bypass the fingerprint lock.

On July 25, Jain and his research team called Rathbun back into their lab to try unlocking the phone for the third time.

Figuring most people naturally hold their phones with their right hands, they decided to try using the enhanced 2-D image of his right thumb first.

Mission accomplished. Jain, Cao and Arora successfully bypassed Misiak’s smartphone that was locked with a fingerprint encryption by using the image of one fingerprint.

Arora said there was a moment of silence before everyone in the room started cheering and giving each other high-fives to celebrate what they had just accomplished.

“We couldn’t believe it,” Arora said. “Kai is so happy, he is still speechless.”

The first thing Rathbun did to the now unlocked phone was disable the fingerprint lock and replace it with a passcode.

Rathbun has been searching for clues that could lead to a possible suspect in Misiak’s phone since Jain and his research team unlocked it. He said the process might still take him a while before he can update Lansing Police with any new information.

“Hopefully there’s a way that this (technology) can be scaled to other police departments ... and those phones that do have valuable information to put people away who deserve it, we can get to that information now hopefully,” Rathbun said.

Samsung expressed concerns about Jain and his team’s recent breakthrough.

In a statement to digital news outlet Quartz, Samsung said:

“Samsung takes fingerprint security very seriously, and we would like to assure that users’ fingerprints are encrypted and securely stored within our devices equipped with fingerprint sensors. As the report itself points out, it takes specific equipment, supplies, and conditions to simulate a person’s fingerprint including being in possession of the fingerprint owner’s phone to unlock the device. If at any time there is a credible potential vulnerability, we will act promptly to investigate and resolve the issue.”

Arora said that while he is thrilled with the work he, Jain and Cao had accomplished, he wants to be clear that the primary purpose of researching fingerprint technology is not to hack into smartphones, but to prompt developers like Samsung to improve the security on their phones for people who use them.

“It’s always a great thing to see our research in practice,” Arora said. “For instance, if I build an algorithm, I would want to see it in a product. So it always makes me happy to see that other people are using it. In this case, we had demonstrated that you could unlock a phone. It’s not to say that we are hackers, but to tell (developers) that their technology is not secure and they need to do something to improve it.”

Jain expressed the same sentiment and stressed that his work is not about continuously helping police solve crimes.

“I hope this doesn’t happen too often,” Jain said. “It’s stressful for us, too, and that’s not our main objective in doing basic research. But if it helps other people, then that’s fine.”

Arora said no one on the team knew they were helping to solve a homicide case until he saw that MSU police mentioned their scientific breakthrough on Facebook.

“Earlier we were just told that this is a guy who had died,” Arora said. “We didn’t know how he died or who killed him, just that these are his fingerprints from an earlier arrest. That’s all we knew.”

No one from Jain’s team was paid to conduct this research for the MSU and Lansing Police departments.

“All we know is that we helped them and hopefully they get some vital clues to solve this case,” Arora said.