The Chinese New Year is to Chinese culture what Christmas Eve is to those in the U.S., said supply chain management senior Jason Wang. So when his group-mates wanted to work on their project that night, as opposed to the night of the MSU-U-M basketball game, he found it difficult to explain the event’s cultural significance.

“I try my best to fit in the group, but somehow it still can be hard,” Wang said. “(It’s) not quite language; (I) took the language test.”

For many Chinese students, conversing with and understanding the vernacular of domestic students can be a taxing experience — the slang, jokes and cultural references used are rarely understood unless explained by the speaker or researched.

Many internationals students, including those from China, develop relationships with their domestic counterparts. But while these cross-cultural communication barriers also exist for most international students, what distinguishes the Chinese student population is their numbers.

For some Chinese students, the high number of fellow nationals on campus provides a way to mostly avoid these interactions with domestic students and develop an insular social life. And with such a large minority population comes numerous stereotypes.

Numbers and stereotypes

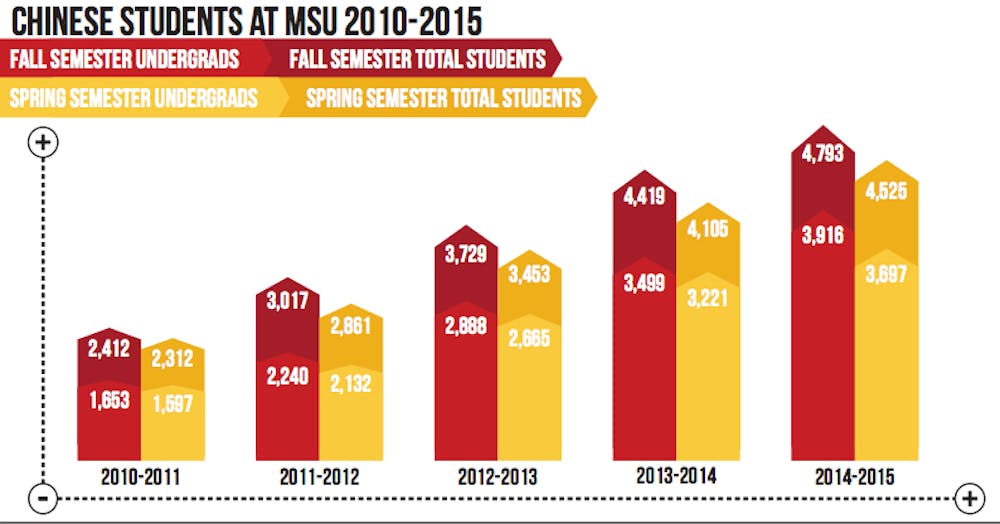

From fall 2010 to spring 2015, the Chinese undergraduate population exploded, increasing by nearly 124 percent to the 3,697 students it is now, according to Office of Planning and Budgets' data.

Being a student among MSU’s largest international student body is both a boon and a detriment, Office for International Students and Scholars assistant director Liz Matthews said.

When international students first arrive at MSU, the differences in how they adjust is minimal, Matthews said. But in the following first weeks, that’s when population size factors into social patterns.

“Our Chinese students have an additional challenge of having to decide if they want to get to know people who are not from China,” Matthews said. “Whereas our students who come from countries that are not so represented, they have no choice.”

At University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where the Chinese student population rivals that of MSU and East Asian Languages and Cultures associate professor Gary Xu teaches, Xu said he’s observed similar patterns.

“They don’t have to go outside their own group to have a social life, to not feel lonely, to learn about the course requirements, to learn about everything,” Xu said.

One of the stereotypes surrounding Chinese students on campus is that they’re cliquey, that they stick to their own and rarely branch out to others, applied engineering junior Steven St.Pierre said.

But, having made friends with several Chinese students, St.Pierre has seen both the truth and falsehood of this stereotype, he said.

Awhile back he spotted a Chinese friend sitting in a dining hall with two fellow nationals and decided to eat with them. The entirety of the time they sat together, the two other Chinese students didn’t speak and were standoffish, he said.

St.Pierre attributed their behavior as a reaction to another stereotype from domestic students that Chinese students face — that they’re unintelligent because of the way they speak.

“(Domestic students) give them a lot of hell because they seem slow,” St.Pierre said. “But if you come to a new country, where everything is different, everything becomes a lot harder.”

Being from a small town in northern Michigan where the population is predominately white, construction management sophomore Jordan Jelinek said coming to MSU has helped him better understand other cultures.

In classes at MSU, Jelinek has made friends with several Chinese students. Through those interactions he said he came to a realization of what differences lay beyond the cultural distinctions, he said.

“(The Chinese students) in my class, they’re not that much different from us,” he said.

But, he said, there are pervading stereotypes of Chinese students that deter domestic students from interacting with them — namely, that grouping all Chinese students as having wealth and luxury cars can make them seem stuck up.

Journalism senior Mandi Fu said the stereotype that Chinese students who study abroad as being wealthy is one faced in China as well as in America. And it’s a stereotype, she said, that only holds true for a minority of the Chinese population at MSU.

“I would say probably 20 to 30 percent here are truly rich,” Fu said. “My mother is a teacher, and my father is in engineering. I only have a Honda car. And I’m happy.”

Lost in translation

The only remedy for reaching out to domestic students and overcoming the available comfort of a large community of fellow nationals, or for what he calls taking the “first step,” is bravery, Xu said.

The bravery that Xu speaks of isn’t just triumphing over social anxiety, extending a hello or understanding the English language, it’s the endurance to work past complex cultural-linguistic barriers that, when attempting to cross for the first times, contain the possibility of embarrassment and misunderstanding.

Many Chinese are taught English at an early age and are required to display their knowledge before admittance into U.S. universities, he said. But this learning and testing is often restricted to memorization of words and grammatical employment, not everyday situations where vernacular is encountered.

“They were taught to memorize the words but not to put them into actual use,” Xu said. “Bars, streets, car dealerships, the basketball game — they have to be practiced in actual situations. If they don’t encounter these situations in their learning process, (it can be) very difficult.”

For Fu, the hardest adjustment to studying in the U.S. has been understanding and mastering those subtle elements of everyday, domestic student speech — how a conversation is started, what topics are discussed and how to speak informally.

“It’s culture stuff, it’s not only the language,” Fu said. “Even though you’re good at language, you can’t really solve some cultural problems, which will make some problems and misunderstanding.”

The process has been gradual, she said, and it’s been aided by picking up off conversations across campus, from the classroom to the dining hall. In being able to better express her feelings and opinions in English, she said she’s more comfortable in talking in the language to native speakers.

Exchange of culture

Cross-cultural communication barriers are a decisive factor for Chinese students in particular, Chemistry doctoral student Yongle Pang said, because there’s a safety net for them, a social life without new complications.

But these students, along with domestic students who only socialize within their own nationality, won’t experience the cultural exchange that can provide different approaches to shared problems, Pang said.

The use of words or phrases inappropriate for the context can often create misunderstandings that hinder Chinese students from developing friendships and bonds with domestic students, Wang said.

Awhile back, Wang and his friend were telling their food selections to a dining hall workers, when his friend unintentionally came off harshly. Rather than asking if he could have something, the friend told the worker only what he wanted, Wang said.

Although many domestic students intentionally, or uncaringly, do the same, Wang said the story highlights a trouble that many international students face.

“(There’s) an uncertainty of how to act in the American way,” Wang said. “When acting inappropriately, (we’re) often directed but not told why. You want to teach him how to fish, not just give it to him. I think we really need that kind of help.”