Exiting the elevator on the third floor of Spartan Stadium, it’s clear the office of University Advancement is tailored to impress.

Floor-to-ceiling windows offer sweeping views of campus’ western edge. Heading the university’s advancement efforts is Robert Groves, MSU’s vice president of university advancement.

Groves comes across in conversation as a person with deep convictions about the university’s mission, and while it’s difficult to dispute the sincerity of his “I ‘heart’ MSU” coffee mug, he is far from a lifelong Spartan.

Until 2009, Groves was the second-in-command for the University of Michigan’s advancement efforts. Previously he had worked for the University of Minnesota, and before that Pennsylvania State University and first for Ohio State, where he went to school.

Groves was recruited by MSU with an offer to head the university’s advancement efforts, and a bump to a salary that was already solidly in the six figures.

Two years after Groves took the job, the university privately began a new capital campaign called “Empower Extraordinary,” a coordinated fundraising effort to raise $1.5 billion. The public portion of the campaign was unveiled Oct. 24 with considerable fanfare at Wharton Center, after already having raised $780 million privately.

Groves’ appointment, and MSU’s advancement efforts as whole, are indicative of the importance private donations — and the business of acquiring them — have gained at public universities.

It reflects a future where capital campaigns become a perpetual cycle at MSU, because now “every institution is either in a campaign ... or they’re post-campaign,” said Rob Henry, executive director of emerging constituencies at the Council for Advancement and Support of Education.

Late to the game

MSU’s $1.5 billion goal is dwarfed by some other universities in the Big Ten. U-M’s latest campaign has a goal of $4 billion. Northwestern is shooting for $3.75 billion. Penn State’s most recent campaign exceeded $2 billion.

University officials offhandedly quip that MSU is “playing catch-up” in the fundraising game. In the past, though, MSU wasn’t in the game at all.

“John Hannah didn’t want to raise money, he didn’t like to raise money,” President Lou Anna K. Simon said. “Our peers were aggressively fundraising for that margin of excellence.”

John Hannah, who was president of MSU from 1941 to 1969, oversaw MSU’s expansion into a major research institution but did little to promote fundraising.

“(Hannah) believed his mission was to the state of Michigan, and the legislature would support it,” Groves said.

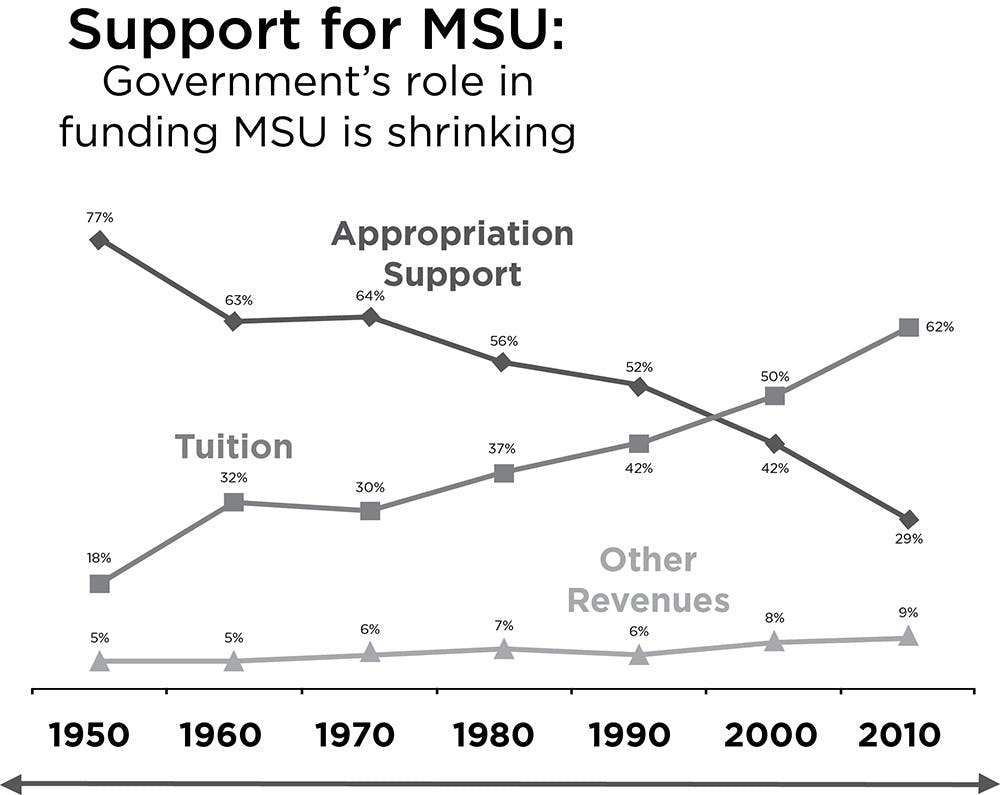

Henry said that’s no longer the case for most universities, especially MSU.

“That number is dwindling, in terms of state support,” Henry said. “Now many institutions, the livelihood and the opportunities for growth in institutions is through individual giving.”

As a result of the reluctance to embrace fundraising, Simon explained, a culture of philanthropy didn’t flourish.

“We didn’t lay the groundwork 30 or 40 years ago, so we’re not benefiting today from the maturity of those gifts,” Simon said, referring to the fact that many alumni do not provide significant donations until later in their lives.

Groves said building that culture is something that will take a couple of generations.

“Fundraising is more than just what you do today. It’s really building a culture among your alumni and you students that understand this is an important part of what keeps the university strong,” Groves said. “That’s more than what you can do in a single campaign.”

Still, he said MSU’s current goal is the result of significant research, and is a benchmark officials are confident can be met and even exceeded.

The role students play

A key component of bolstering MSU’s ability to fundraise is cultivating a “culture of philanthropy” within the students currently at MSU, so the university can benefit far in the future.

“You want to get students engaged, because ... they will be the ones supporting these capital campaigns,” Henry said.

But Josh Brawley, a communications senior and manager at MSU Greenline — which is the student face of MSU’s fundraising efforts — said the university has a lot of room to further a culture of philanthropy.

He said while Greenline employees are very aware of the importance of donations, the rest of the student body isn’t cognizant of fundraising efforts.

“I definitely think there is a lot more work to be done,” Brawley said. “That’s really our goal, to get (students) to give right after they graduate. ... We’re really trying to make sure that we do get year-to-year donors, but unfortunately there’s still probably a long way to go.”

In a previous interview with The State News, MSU Trustee Brian Mosallam noted there is a “disconnect” students must move past.

“When I graduated from school and I received a call from the College of Engineering to make a donation, I didn’t understand the importance of it,” Mosallam said.

Simon spoke of the volunteers in the charity event Alex’s Great State Race as an example of students developing the sort of “philanthropic habit” that will benefit the university in the future.

“I’m just really, really proud of the students in their engagement of activities that also contribute, even though they’re stretched for dollars,” Simon said. “The groundwork is being laid, and that takes time.”

Big targets

On the eve of the U-M football game, a massive white tent had been erected next to Beaumont tower. Students walking by could hear soft jazz, the clink of cutlery and the murmur of conversation.

Inside the tent were about 700 diners, both prospective donors or those who had already given MSU at least $100,000.

Groves emphasized every dollar donated to MSU is significant, but it’s evident the wealthiest donors are the driving force behind MSU’s fundraising efforts.

MSU Greenline reaches over 175,000 of MSU’s more than 450,000 alumni each year, resulting in about $4 million donated from 50,000 of them, according to Greenline’s website.

But in the 2014 fiscal year, MSU had about $210 million in donations, meaning the efforts of MSU’s telemarketers would represent just 1.9 percent of that total.

As a rule, Groves said, in university capital campaigns, 1 percent of the gifts represents about 80 percent of the dollars. In MSU’s last campaign, they represented 83 percent.

The university looks to target directly alumni who donate $100,000 or more, a pool of about 10 to 12,000 alumni. They are assigned relationship managers, university advancement employees that act as personal contacts to the prospective donors.

MSU targets them through what Groves characterized as a “matrix.” While there are development teams within each college, targeting alumni of specific major programs, there are also about 14 employees around the country that work in specific geographic areas.

Each person can look over alumni records which can provide detailed demographic data and target 150 to 200 alumni in their areas, which can vary from just Chicago to entire regions, developing relationships with them “on a very personal level,” Groves said. He estimated about 20 of the prospects end up making major gifts.

For major gifts, ironing out the details of how donations in excess of a million dollars are used is not unlike a negotiation. Lawyers from both sides meet and work on a contract. Eli Broad’s recent $25 million contribution to MSU was the result of a three- to four-month process, Groves said.

More sophisticated work

After MSU’s last campaign, which ended in 2005 and raised more than $1.4 billion , Simon said it became clear MSU “needed to be very skillful in raising private dollars,” spurring Groves’ recruitment. He had just finished overseeing a $3.1 billion capital campaign at U-M and had campaigns at several other universities under his belt.

“He really helped to hopefully leap over some of our competitors in terms of what systems we should put in place, how we should be organized,” Simon said. “He brought with him the lessons of other (institutions).”

As Groves entered his new position, the Office of Advancement was restructured to also encompass the Alumni Association. The office is now comprised of more than 240 employees.

“Without a doubt, there are some elements that are profit oriented,” Henry said. “We don’t like to compare our work to sales, but the more people you have on your sales team, the more likely you are to increase your overall revenue.”

And Simon said she is confident that revenue will continue to increase.

“That campaign really set the stage for the more sophisticated work we’re doing now,” Simon said.