Editor’s note: This story has been changed to reflect that Victoria Johnson was one of four black students on her floor.

After growing up in Southfield, Mich., food industry management senior Victoria Johnson was excited to enroll at MSU and join a big college campus with a greater level of diversity than her hometown.

Although Johnson, who is black, said Southfield is a predominantly black city, she attended a Catholic girls high school in Farmington Hills, Mich., where she was one of a very small number of black girls.

When she arrived in East Lansing and moved into Case Hall, she was surprised to learn she was one of only four black students on her floor.

“I thought I would be around people who looked like me, and I wasn’t,” she said. “I’ve always been the only black person in the group … and (after moving in), I just thought, ‘I guess it’s just going to be like it’s always been.’”

To create racially and culturally diverse neighborhoods, the university uses a round-robin format to place first-year students in residence halls, but disproportionate racial representation has remained an issue, said Amy Franklin-Craft, the associate director of the Department of Residence Life.

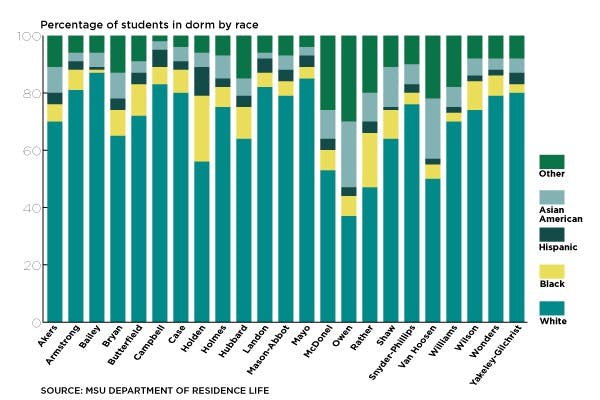

According to enrollment numbers provided by the Office of Planning and Budgets in the 2011 Data Digest, 73 percent of undergraduate students identified themselves as white, 7 percent identified themselves as African-American/black, 4 percent identified themselves as Asian and 3 percent identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino.

However, based on data from the Department of Residence Life in the World 2010.pdf, very few residence halls have a racial makeup similar to the university averages, leaving many wondering whether the imbalance is a result of student choice or institutional bias.

Bridging the gap

When interdisciplinary studies in social science senior Devin Evans moved into Hubbard Hall as a freshman in fall 2008, he joined the hall with the second highest percentage of black students. In 2008, 29 percent of the students in Hubbard were black, trailing only Butterfield Hall, where 38 percent of the students were black, both halls well above the university average.

Evans, who is black, said he has heard residence halls receive nicknames because of the racial makeup of the students they house, such as Brody Complex Neighborhood being referred to as “the Brojects.”

Although finding it comforting to be around a large number of students from a similar background, after two years in Hubbard, Evans knew he needed a change.

The following year, he moved into Snyder Hall, where, combined with Phillips Hall, 76 percent of the students were white — 25 percent higher than the percentage of white students in Hubbard his first year — and became an intercultural aide.

“Part of (the) reason (I became) an intercultural aide was staying in my own community, the black community, my first two years,” Evans said. “I wanted to bring people together and … help students understand that there are other students that are from groups outside your own and it’s important to interact with them.”

This year, Evans is an intercultural aide in Wilson Hall and said encouraging students to interact with people from other racial and ethnic backgrounds has been a difficult process.

Evans said the intercultural aides in Wilson and Holden Halls are working together to hold a variety of intercultural events as a way to bring students together.

“(In) both places, it has been very difficult getting people to break people off from their shell of friends,” he said. “We have to have intercultural events to allow people to interact with other people because they probably wouldn’t do it by themselves. It helps to bridge the gap.”

Johnson, who also is an intercultural aide, said she lived in Landon Hall her sophomore year and didn’t notice an improvement in diversity. West Circle Neighborhood’s fall 2010 average was 80 percent white students.

“I wish it was different, but that was something I was used to,” she said. “I just felt like it was so divided, and there was no one I could talk to about cultural issues.”

Sizing up segregation

Geography professor Joe Darden said he has studied urban geography, along with the causes behind segregated communities, for a number of years.

Segregation doesn’t have to be an intentional or purposeful act, but merely an uneven distribution of people when compared to the average for the area, Darden said.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

“Most students come out of segregated communities — that is the American pattern,” he said. “You end up lacking a very important piece of knowledge … (and) you’re less well-rounded than you could have been.”

Franklin-Craft said before 2009, incoming freshmen were allowed to request their residence hall, which she believes resulted in self-segregation.

Although the numbers have improved slightly after the change, Franklin-Craft said MSU still isn’t where it needs to be.

“There was absolutely a self-segregation that was happening across campus,” she said. “Students coming into Michigan State may not have had that experience of working with students from other backgrounds.”

In order to break the pattern of segregation, Darden said the university must create a policy of integration, in which each residence hall represents the university’s racial average.

Without this policy, Darden said students will continue to perpetuate the divided living experiences they learned as children because it’s the only experience they’ve had.

“Knowledge is what a university is supposed to present to students, and knowledge comes in different forms,” he said. “It’s clear if they don’t do it the outcome is segregation and the outcome will be students are no different than when they came in. … That’s a price the university pays. That’s a choice.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “Disproportionate diversity” on social media.