In the very front of Michigan State University’s boardroom, Barry Powers restlessly ruffled through a mess of documents and legal pads in his two oversized briefcases.

As the trustees debated infrastructure plans and a new room-and-board rate, the Mount Clemens attorney popped mints and combed his hair, preparing to speak during the meeting’s public comment period.

When his brief time-slot came, he pulled nine copies of a lawsuit out of an Adidas drawstring bag and walked up to the podium.

"Arts, science, letters, humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, mathematics, music, agricultural applications, business, manufacturing, medicine, law, the truth, scientia, knowledge!" he yelled. "This is your mission."

"What is not within your purview?" he asked.

"Social justice; ideologic, religious, or spiritual proselytization; anti-American radicalism; yellow journalism!" he answered, slamming his fist for emphasis.

"Court of Claims. You’ve been served."

Before he could sufficiently explain the matter that brought him before the board, his time ran out and he was told to take a seat.

The spectacle was an unusual departure from Friday's routine meeting. Powers' speech was met with confused shrugs among the board, a stray laugh from a faculty senator, and a subdued smirk from the university’s general counsel.

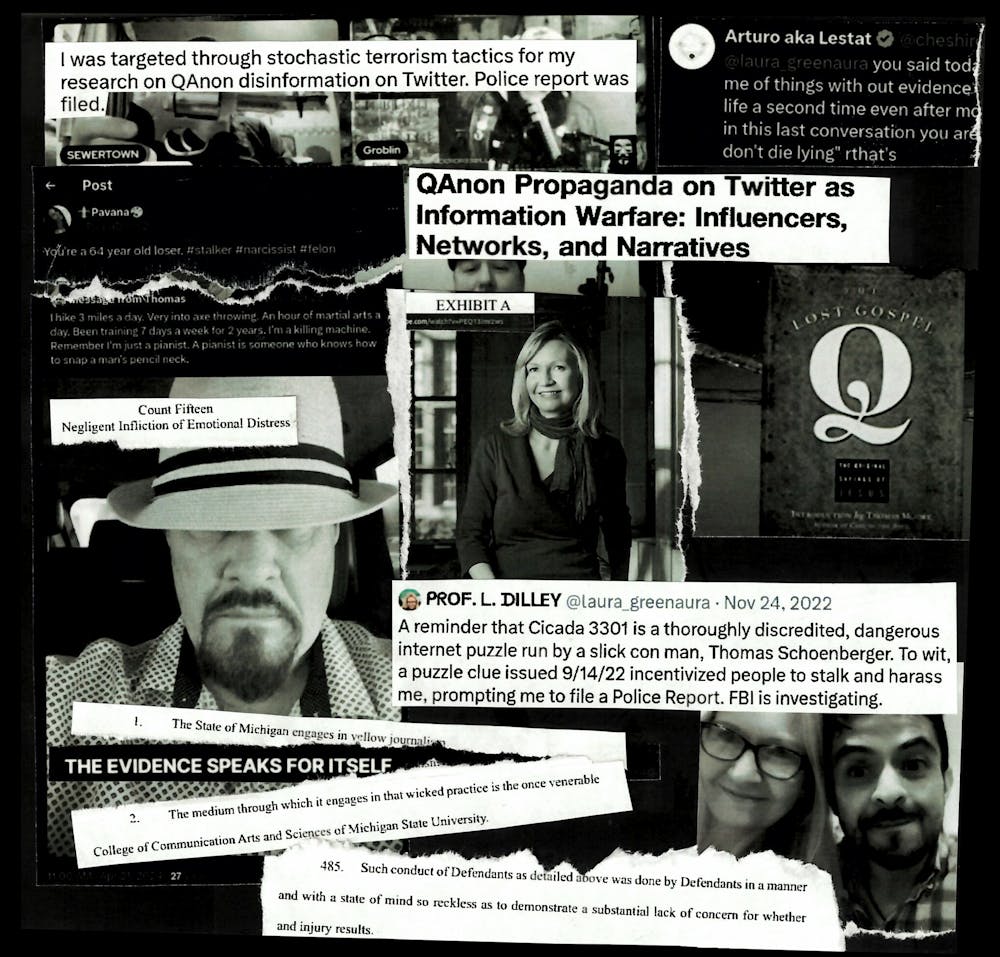

A more knowing reaction could be found across the room. There sat Laura Dilley: an MSU professor whose research paper and incendiary social media posts had set off an elaborate online feud with Powers’ client, Thomas Schoenberger.

He's known as an architect of cerebral puzzles to some and a notorious online provocateur to others. Dilley’s research gave him a new moniker: "QAnon insider."

Schoenberger detests the characterization, claiming he has no involvement with the extremist conspiracy. In legal filings, he paints himself as an entirely apolitical 64-year-old composer, who only has a penchant for eccentric puzzles and mesmerizing YouTube videos.

The lawsuit argues that his reputation and ability to work have been crippled by Dilley’s claims, including that he helped promote QAnon, had Russian operatives harass journal editors and may have caused the mass shooting on MSU’s campus in 2023, among others.

Schoenberger frames his actions to correct the record as a righteous crusade against a crooked academic. Dilley, however, calls them a campaign of retaliatory harassment.

No matter the interpretation, the lawsuit pulls MSU into a longstanding feud that’s ordinarily confined to an odd alcove of the internet. If Schoenberger gets his way, the board meeting will be only the beginning. Fights that feel more at home on anonymous blogs will become the business of university lawyers and Michigan courts.

Each member of MSU’s Board of Trustees and two ostensibly unconnected faculty members are Dilley’s co-defendants in the sprawling lawsuit, which asserts a series of cryptic hypotheses trying to pin blame for her alleged misdeeds on the university.

Whether those theories swiftly unravel or firmly take root, the case certainly underlines a number of tensions for the growing league of academics who study online misinformation. At play are questions about how universities and academic journals can best handle contentious research about the often volatile world of the internet, and about what happens when scholars who intend only to study it find themselves entangled in its unearthly orbit.

Dilley’s case represents a rather extreme example of that phenomenon. She claims her involvement began as a purely academic pursuit, but today, the professor is perhaps more of a character in the hyper-specific internet subculture than a chronicler of it.

It was a transformation that happened over years of cryptic Tweets, a series of appearances on a sewer-themed podcast, multiple complaints about the veracity of her research, and a romantic entanglement with a conspiracy-insider turned research-partner turned disgruntled double-agent.

At the dispute’s outermost surface, there is a simple debate about the veracity of a research paper. But dig any deeper, and you’ll find a Gordian Knot of obsessive actors and outlandish arguments on all sides of a longstanding battle easily deemed incomprehensible by anyone other than those inside it.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

The professor and the provocateur

QAnon was not a logical research subject for Dilley. The professor’s previous publications focused on the science of hearing and speech in children with cognitive disabilities, not the extremist conspiracy theory creeping into the nation’s mainstream political discourse.

But, it was 2020, and she had tenure. The pandemic was bringing not just shutdowns and sickness, but an unprecedented avalanche of online misinformation.

"Lots of people took up hobbies in COVID," she told The State News. "Some people took up knitting, others took up baking. My hobby was learning to analyze Twitter data using computational metrics and studying QAnon."

The theory suggests that a cabal of deep-state Democrats who engage in cannibalism and pedophilia lead a global child sex trafficking ring, but are being secretly prosecuted by Donald Trump. It centers around the cryptic posts of a supposed government insider known as "Q." The FBI once labeled it a domestic terrorist threat.

Dilley’s 2021 paper — "QAnon Propaganda on Twitter as Information Warfare: Influencers, Networks, and Narratives" — attempts to undermine the assumption that the conspiracy naturally collected support as a grassroots campaign, instead pointing to "evidence of large-scale coordination" among QAnon-related accounts. It suggests Russian operatives could have helped orchestrate the rise of QAnon due to overlap between accounts that promoted QAnon and those that spoke Russian.

The paper also notes an overlap between QAnon-related accounts and accounts that promoted other extremist content, like antisemitism; accounts that promoted New Age and occult themes; and those that were involved in internet puzzles.

That last finding is where Schoenberger comes in. Citing data pulled from Twitter, the paper shows how Schoenberger’s Twitter accounts were very popular in online QAnon circles, as was Cicada 3301, a highly mysterious internet puzzle game popular in the early 2010s.

Online onlookers, including Dilley, have long speculated that Schoenberger "gamejacked" Cicada from its true creator when he incorporated it as an LLC in 2014, though he denies the allegation, saying it was a collective that he wrote music for and contributed ideas to from the beginning.

It’s one of several internet feuds that Schoenberger is wrapped up in. While a cursory Google search presents him as nothing more than an unconventional musician, on the deeper corners of the web critics say that Schoenberger is an internet troll, a manipulator, a hypnotist, a cyber stalker and even a rapist; he’s been accused of causing mental breakdowns and impersonating a doctor. (Schoenberger vehemently denies all such claims.)

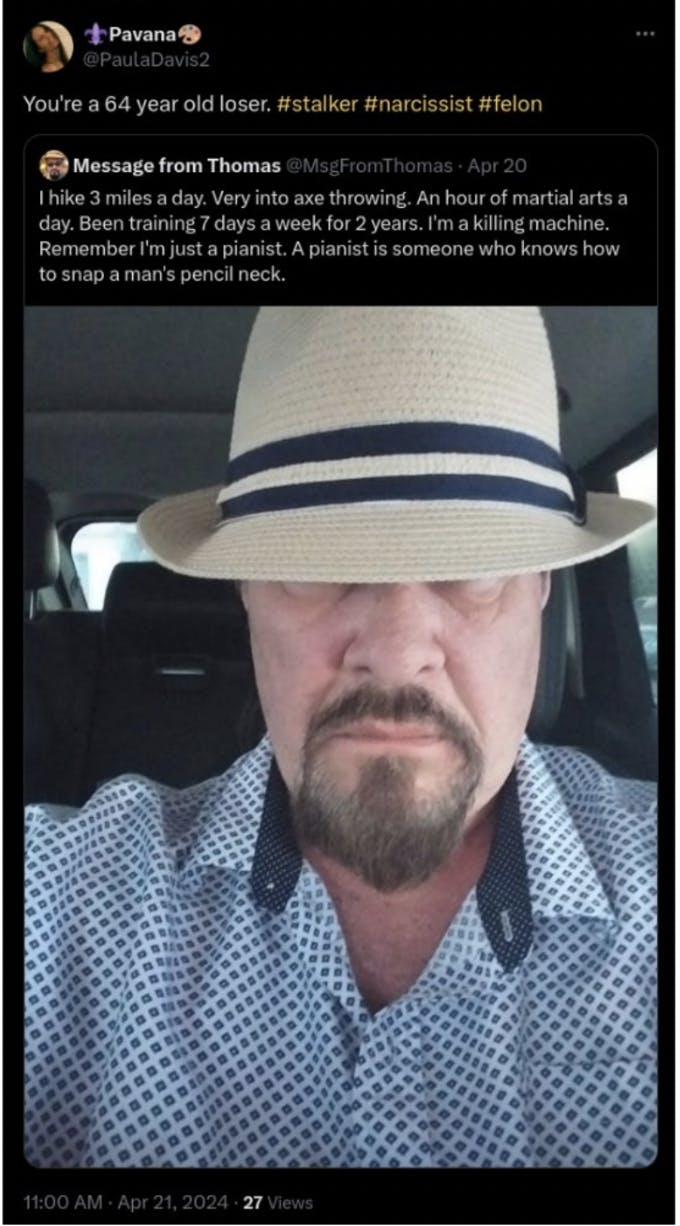

He does concede some oddities: His organization believes that "God can be perceived through frequencies, sounds, and music;" he once described himself online as a "killing machine" thanks to his regimented martial arts and axe-throwing; and his own lawsuit identifies him as "one of the most neurodivergent individuals living."

At least once, Schoenberger ventured from far-flung internet enclaves to huddles with high-profile right-wing politicos. In a sworn deposition, he admitted involvement in a planned wiretapping scheme targeting the parents of DNC staffer Seth Rich, whose sudden death fueled far-right conspiracy theories (though Schoenberger insists he ultimately refused to go through with it).

The academic veneer of Dilley’s assertions have emboldened Schoenberger’s detractors, giving them an apparently reputable claim connecting him to the nationally derided conspiracy theory.

QAnon claims

Dilley’s paper asserts that Schoenberger was "involved in early promotion of QAnon narratives" and that he may have groomed Cicada 3301 participants into posting as "Q." These claims were not attributed to her findings from the Twitter data, but instead to a barrage of obscure, since-deleted news articles and blog posts. Asked about the veracity of the sources, Dilley told The State News she was unconcerned, pointing out that none of the peer reviewers who examined drafts of the paper had issues. (A separate, unpublished manuscript furthered these claims, according to the lawsuit. That research claimed Schoenberger used "psychological warfare methods" to "spread QAnon narratives," among other things.)

The research generated some legitimate discussion. It was promoted by MSU on social media, and its findings were covered in several mainstream news outlets, including Business Insider, Rolling Stone and Financial Times.

In the years since, Schoenberger has denied any involvement with QAnon, repeatedly criticizing Dilley and the veracity of her paper on social media. His pushback has escalated in recent months. First, he sent legal letters to the professor and MSU demanding a retraction of the paper. When those pleas went unanswered, he filed his lawsuit in Michigan’s Court of Claims last month, naming Dilley and MSU as defendants. (The university declined to comment on the pending litigation.)

Schoenberger’s complaint argued that while his internet puzzles are "deeply mysterious," they aren’t cultish or political, and he has no involvement with QAnon. He takes issue with the underlying logic of the paper’s mathematical analysis of Twitter, arguing that just because someone interacted with a QAnon-related account doesn’t mean they are connected to the conspiracy.

"Dilley's analysis method is equivalent to saying: if you talk to someone, or even read what others say, then you get ‘contaminated’ by them and can be accused of sharing and supporting their views," Schoenberger wrote in an email to The State News. "Even a conversation to learn what another person thinks, and to express disagreement with them, qualifies as being a member of their ideological camp."

Dilley told The State News her research was not meant to be a definitive picture of who was involved in QAnon and why, but instead a "snapshot" of social media circles at a pertinent point in history that further research could be based on. The research, which used quantitative methods to track and map Twitter interactions, is of a limited scope, she said, suggesting a non-academic like Schoenberger might be confused by the discursive nature of academic papers.

In ways, Schoenberg’s complaint does distort some of Dilley’s statements. It claims, for example, that the paper called Schoenberger the "mastermind behind QAnon." But, the phrase was taken not from the text of the paper, rather an article cited in the appendix, titled, "Is Thomas Schoenberger the mastermind behind QAnon?"

Schoenberger’s lawsuit attempts to establish great financial consequences resulting from Dilley’s claims. It says she ruined a row of lucrative business opportunities Schoenberger had in the works, including two game show deals, a book deal, a partnership for games and even a TV show "based on his creative product and skills."

Disputes over publication

Schoenberger wasn’t the only person who had concerns about Dilley’s research connecting them with QAnon.

Also upset was communications consultant Trevor FitzGibbon, who ran a major progressive PR firm until he was accused of sexual misconduct in 2015 (a U.S. Attorney investigated the claims and declined to file any charges). He also briefly worked with Schoenberger on an "online reputation management" firm called Shadowbox.

Dilley’s paper calls FitzGibbon a QAnon insider, a finding touted in a presentation of Dilley’s research promoted by MSU’s official social media accounts and Tweets she posted. Frustrated, FitzGibbon messaged Dilley on Twitter disputing the allegation and threatening to sue. She didn’t respond to the legal threat, according to screenshots both shared with The State News.

FitzGibbon maintains that he has never subscribed to the QAnon theory or worked to promote it. In fact, months before Dilley’s paper, he authored an op-ed criticizing QAnon while warning that "online operatives are turning Q accusations into modern-day Salem witch trials." Like Schoenberger, he conceded that it's possible he could have had interactions with people who subscribed to the theory, but "that’s just guilt by association … it’s saying that if I knew somebody five years ago, and that person turns out to be crazy, now I believe what they believe."

"There’s gotta be some calculated reason why she’s doing this," he said. "This is a professor at MSU, I don’t think they would employ somebody who is actually insane."

Dilley’s paper also labels web developer Suzie Dawson as a QAnon insider, despite her being one of its earliest detractors, according to her colleague, Sean O’Brien, a cybersecurity instructor at Yale Law School. He was one of several critics who wrote to the academic journal Frontiers in Communications demanding that it rescind its offer to publish Dilley’s paper.

Dilley told The State News that her list of QAnon insiders was an "educated guess" of individuals that were known or suspected of promoting QAnon, based on a combination of largely-unpublished Twitter data sets, news reports and "a number of podcasters / YouTubers" she had been listening to at the time. Dilley acknowledged that she could have chosen a different descriptor for the list, but she liked the phrase because it "described and identified a number of accounts that (she) thought deserved further scrutiny, even while providing rigor to the level expected in academia to warrant acceptance at a well-respected journal."

Dawson and FitzGibbon were on the list, she said, because they promoted people who she says promoted QAnon. Perhaps it’s relevant that Dawson and FitzGibbon have both vocally criticized the conspiracy, Dilley admits. But, "One can be a supporter of QAnon, either directly by promoting it, or indirectly, by platforming and working with individuals that were themselves vocal QAnon proponents."

Dilley attempted to protect publication, writing an email to journal editors that said "people all over the world are waiting for this article to come out” and claiming that O’Brien and Dawson were harassing her and conspiring with Schoenberger. Dilley told The State News that she believes the pair objected to the paper because of some connection to Russia, making a vague assertion about them appearing on state media and connections to a "Moscow blockchain organization."

Dawson and O’Brien said the reason for their outreach was to address what they saw as flaws in Dilley’s research. Both denied even knowing who Schoenberger is. If anything, O’Brien said Dilley’s defense underlines the issues with her research altogether.

"Prof. Dilley seems to place me and many others in whatever conspiracy she finds compelling for her narrative," O’Brien said in an email to The State News. "These kinds of conspiratorial corkboards of connections with pins and strings between people who have never met is a major flaw in her analysis of social networks and Internet-based communities."

Other scholars and faculty advocacy groups also wrote to the journal saying they supported Dilley and hoped to see her paper published. But, their efforts were fruitless.

After two months of consideration, the journal wrote to Dilley saying editors had investigated the "concerns raised" and ultimately decided to rescind their offer to publish the article. Editors said they determined it violated a section of the journal’s policy on ascribing negative labels to individuals without their consent. They did not specify what parts of the paper violated the policy.

Dilley said she would have changed how she labeled the list of QAnon "insiders," if the journal had given her that option. Instead, Dilley took their abrupt decision as proof they had been harassed into submission. (When asked about that claim, a spokesperson for the journal repeated what it told Dilley, and declined to clarify further.)

With the paper’s chances at being published in the journal shot, Dilley opted instead to publish online in an open-access archive. The listed co-authors on the paper are Faith Foster, then an MSU undergraduate, and William Welna, a computer programmer who helped collect the Twitter data underpinning the paper. Welna did not have experience with academic research and, asked by The State News, Dilley declined to explain how she found him in the first place.

Welna has since disavowed the project. In a blog post, the programmer wrote that he thought the research would be "strictly academic," but has since been disturbed by "trolling, lawfare, and surrounding personal relationship issues" that erupted after publication. Welna has defended the paper’s findings that were brought forth by the Twitter data he collected, but said "it’s all the stuff after that makes everything very muddled."

The relationship at play? Welna told The State News he was disturbed by Dilley and Schoenberger’s complicated personal and professional history with another credited researcher, Arturo Tafoya, who had no formal experience in research or academic writing when he was credited in the acknowledgements of the paper.

Spoiled romance

A graphic designer based in Mexico, Tafoya first encountered Schoenberger around 2017, when he was asked to produce artwork for Cicada. In a 2023 blog interview, he compared his recruitment to a "school play in front of me where they dazzled me." But his awe quickly faded, he said, as he grew suspicious that the puzzle was a "hijacked version," lacking the secret code that supposedly underpins the real game. Tafoya then became wary of Schoenberger, deciding that "this guy is dangerous and definitely not what he pretends to be." He grew more resentful as he started to believe his art was being used to spread QAnon theories.

"My things were used to create propaganda, my memes, my imagery, the videos, when I saw them with a Q overlap, it made my blood boil," he claimed in the blog interview. Suspicious of Schoenberger, Tafoya said he started asking other Cicada affiliates, "Hey, is Thomas Q?"

"The only answer I got was like, 'I can’t tell you,' and a little giggle," he told the blog. "I was just a new guy and they didn’t trust me that much."

Dilley met Tafoya in early 2021, she said. By then, he was disgruntled and working to archive evidence of Cicada’s supposed connection to Qanon. Their first interaction was purely professional, Dilley said, recounting how she sent him a draft of her paper to get feedback.

Soon after that, their relationship became romantic. Dilley declined to describe exactly how that happened in her interview with The State News, though she did once describe the union in a Tweet, writing that they "fell in love and joined forces … under the looming spectre of internally-known (sic) con-man Thomas Schoenberger."

In a voice memo to The State News, Schoenberger characterized their relationship by saying, "They were having a ménage a trois with me, except I wasn’t there."

In Dilley’s retelling, Tafoya never directly contributed to the research in the paper. Still, he asked her to be credited, she said, struggling to articulate his contribution beyond "a sort of indirect context added by, for example, his archival footage of different Youtubers." In the end, he was not a named co-author at the top of the paper, but is thanked in the acknowledgements as a contributor of "research background" and feedback on drafts. She told The State News the credit was "consistent with a sort of mentor role I’ve long had with students and even junior colleagues or potential grad students."

More than a year after the paper was posted online, Dilley and Tafoya embarked on a new venture: an Etsy store selling Cicada-themed merchandise. "In (Tafoya’s) narrative, it was a chance to inspire people," Dilley said, explaining that Tafoya believed the original Cicada puzzle — before it was hijacked by Schoenberger — was still worth admiring.

In his lawsuit, Schoenberger argues the enterprise infringed upon his ownership of Cicada, saying the couple "planned to exploit (his) Cicada 3301 brand while simultaneously destroying his life." Dilley disputed the claim, saying Tafoya owned the rights to the imagery, because it was primarily artwork he made while working for Cicada. She added that the work was approved by MSU, saying the university told her she could pursue the "side-hustle" if she didn’t spend more than one day a week on it. (The university declined to confirm the existence of such an arrangement.)

Late last year, after the paper and Etsy store, Dilley and Tafoya’s relationship ended acrimoniously. The two exchanged scores of Tweets detailing and dissecting the romance and breakup in graphic detail, with Dilley calling Tafoya a "Psychopathic Narcissist just like Thomas" practicing "extortion, blackmail, bribery, and international conspiracy."

Tafoya, in turn, posted screenshots of hundreds of profane text messages exchanged between him and Dilley amid various fights. In them, he complains that Dilley kept a secret Tinder account during their relationship (Dilley says she only did so to see if Tafoya had one, which she says he did), while she says that his “life is over” without her and criticizes his use of various drugs.

The fights apparently prompted Tafoya to attempt suicide, according to his Tweets. That has since given way to a persistent online theory pushed by Schoenberger’s followers that accuses Dilley of "bullyciding" Tafoya to silence him. Dilley has called the entire saga a "hoax," saying a medical assistant told her that Tafoya’s mother disputed that he attempted suicide at all.

Schoenberger once supported the "bullycide" theory but has recently disavowed it, saying that "based upon the evidence that we have seen, the suicide attempt or attempts are not real, but I suspect it's because Arturo and his family are terrified of the professor." (After initially agreeing to an interview with The State News, Tafoya stopped responding to outreach from reporters.)

In the time since the breakup, Schoenberger claims that he and Tafoya have reconnected and are working together to get back at Dilley. Their newfound alliance has apparently allowed Schoenberger access to Dilley’s personal files, which he says Tafoya obtained through a shared digital file-sharing system they created during the relationship.

Among the items Schoenberger acquired and posted online or shared with The State News are excerpts from a draft of Dilley’s autobiography, a series of graphic sexual communications exchanged amid the end of her relationship with Tafoya, and emails with colleagues at MSU — which gave way to another one of his theories.

A secondary theory

Drawing on the covertly secured emails, Schoenberger has suggested that Dilley conspired with two MSU colleagues to more effectively target him, placing a seemingly random pair of communications professors among the named defendants in his lawsuit.

Monique Turner, who chairs the Department of Communications, has published research on anger’s role in communication, while her husband Shawn Turner, who is general manager of a university-affiliated NPR station, once held several high-ranking communications positions in federal national security administrations.

Their combined expertise worried Schoenberger.

"I like to keep things normal and not jump to conclusions, but it appears as if MSU was conducting some sort of experiment by incentivizing hatred towards me with a political agenda," he said in a voice memo to The State News explaining his theory that Dilley worked with the Turners to anger and embarrass him.

In reality, the connection between Dilley and the Turners is flimsy.

The lawsuit erroneously claims that Monique Turner is Dilley’s department chair and therefore approved her work. But, the two scholars are in different departments. Dilley’s actual department chair is Dimitar Deliyski, according to university org-charts, as she is in the department of Communicative Sciences and Disorders. (Asked about the error, Schoenberger said, "Well, then they conspired together.")

One of the only times Dilley interacted with Turner was to advise her against engaging with Schoenberger, Dilley said.

In July 2022, Schoenberger sent Turner an email, seemingly under the assumption that she was Dilley’s supervisor, with a cryptic warning. He wrote that "a very deleterious and potentially embarrassing debacle is about to occur on your watch," according to a copy shared by Dilley. He never explained what the "debacle" was, though did make a series of vague comparisons to the Larry Nassar sexual abuse scandal.

Thus ensued a lengthy and confusing email chain that involved a high-profile journalist and a flurry of vague warnings and accusations — all surrounding Turner, who had no control over Dilley’s work.

Rocco Castoro, who leads the outlet The Knows and was once the editor-in-chief of Vice, was CC’d on the email. He replied that he was "a bit peeved" that Schoenberger involved him in the email without prior warning. He called the issue at hand "a serious matter," but never clarified what the issue was.

Castoro also wrote directly to Dilley, saying that "the cat is out of the bag," and that he was referring the matter to two of his colleagues because he didn’t "have the bandwidth to handle Kardashian-level drama." Again, Castoro did not explain the "drama" in question. (Reached by email, Castoro said he "barely" remembers the interaction, describing the situation as "Two idiots fighting over a bone with no meat on it.")

Eventually, Schoenberger chimed back, clarifying that he planned to "formally accuse a MSU professor of sedition and engaging in cyber terorism (sic) against American citizens, using foreign actors. (sic) threats, intimidation tactics, humiliation rituals, and more."

Turner never responded to the barrage of emails. Dilley wrote to her later, explaining Schoenberger’s connection to her research and his "history of contacting workplaces of individuals whom he wishes to intimidate."

"Thanks for letting me know what is going on here," Turner replied. "I am going to ignore these messages."

The other half of Schoenberger’s theory about the Turners posits that Dilley conspired with Shawn Turner to leverage her criticism of him and QAnon into work with the national media and intelligence sector. In an email sent to Turner after a meeting Dilley arranged, she summarized the backlash she was receiving for her research and asked Turner to help her with a communications response to anticipated media attention.

She suggested he could help her break into work with "U.S. defense-related agencies" on things like "psyops" and "narrative warfare," she wrote in the email. And, she stated that she was "very interested in opportunities to become a commentator on CNN," where Turner was a national security analyst. In Schoenberger’s reading, the email is proof that "Dilley’s paper was a propaganda hit-job" motivated by her ambition to appear on CNN and work in the intelligence sector. (Dilley said that while she was interested in where the paper could take her, the pursuit began as a hobby. Schoenberger’s claim is a "load of crap," she said.)

'Holy s— delete this'

For months after the paper was posted online, Schoenberger and his followers worked to discredit Dilley and her research. In her retelling, she was continually harassed and was growing paranoid about her safety. Of particular concern was when she was mentioned, by name, in a supposed Cicada clue. (Schoenberger denied that Cicada clues target individuals, and said the Tweet Dilley was referencing was not an official clue. "If that tweet had said find the professor and kill her, I personally would have notified Twitter," he said.)

Her worries came to a dramatic climax when, on Feb 13, 2023, a shooter opened fire at MSU and an emergency alert was sent to campus. In minutes, Dilley issued a Tweet.

"I was targeted through stochastic terrorism tactics for my research on QAnon disinformation on Twitter," she wrote. "Remains to be seen if there is a connection to the active shooter situation at Michigan State University."

Attached was an earlier post, calling Schoenberger a "slick con man" and claiming that the FBI was investigating him for asking his followers to "stalk and harass" her. (A spokesperson for the relevant field office declined to confirm the existence of any investigation.) Dilley also added a link to her paper on Schoenberger and Qanon.

"Holy s— delete this," a commenter responded. "You are not the main character"

Dilley wrote back, "Of course I am not but if there is any connection then it should be investigated."

"Why would you tweet this in the middle of a mass shooting, is there not enough dis and misinformation floating around?" the critic asked. "You have literally zero reason to think it’s connected. Shameful."

"How would you know?" Dilley responded.

"IDK how to explain to you as an adult and individual of authority at an institution that while your students are literally dying and in hospital it isn’t appropriate to tweet out unsubstantiated claims," they quipped back.

The next day, after the shooter had been identified, Dilley doubled down. She claimed a cryptic tweet from earlier that morning confirmed her fear.

"Don’t cross #Cicada3301 #Real," read the Tweet, posted by a devotee of the puzzle. "Some tried, and are finding out."

Dilley wrote that the post was "a threat to anyone challenging the dangerous Cicada ARG."

"I have eyes & can see & so can others," she Tweeted.

The author of the post, Mindy Waite, said the message was a reference to a separate internet feud and had nothing to do with Dilley, adding, "It is beyond all logic why she would craft this narrative, but she succeeded in causing me to live in fear of my children and I being targeted for revenge by insane internet people who believed her."

Now, more than two years later, Dilley said she stands by the Tweets. "I was sharing what I consider to be a tip, and, like many tips and hunches, it didn’t turn out to be anything." Still, Dilley said that in the moment, she "felt it was important to share a perspective that might draw attention to the Cicada puzzle as something that could be radicalizing or dangerous."

In his lawsuit, Schoenberger claims he "is permanently psychologically paralyzed, traumatized, and in profound fear for the safety and well-being of family, friends, and himself" because of the Tweets. By alleging that he was connected to the shooting during the chaos of the then-ongoing event, he argues that Dilley could have triggered a misguided act of "vigilante justice" against him.

The allegations made amid the shooting may be the most dramatic Twitter-interaction between Dilley and those she studies, but it was by no means the only case. For years, she’s been incredibly active on the platform, constantly interacting with Schoenberger and those in his orbit. Some of the disputes are about the paper, with allies of Cicada lobbing outre critiques, matched by Dilley’s fervid defense. But much of the back-and-forth is fairly detached from her research, with Dilley partaking in incomprehensible feuds involving a slew of Cicada-related theories and an endless stream of cryptic hashtags.

Asked about the Tweeting, Dilley said she views it as an extension of her job. Echoing her assertions about the broad mandate that comes with tenure, she said that "my understanding of my role as a faculty member is that there’s an expectation to be involved in matters of public concern and the debate about key issues."

'Brainwashed'

Beyond Dilley and MSU, the lawsuit comes amid a broader crusade by Schoenberger, who has sent legal letters to a number of his critics in recent months. In his telling, the flurry of litigious demands is a way of reclaiming his reputation from a conspiracy of liars. The recipients, meanwhile, characterized the letters as a series of hollow threats designed to silence them.

One letter went to Tere Joyce Randolph, a finalist on NBC’s Last Comic Standing in 2003 and former pornographic screenwriter who is now a returning student at Fresno State University, where she works for the student newspaper. The January letter she received from Schoenberger’s attorney takes issue with Tweets she posted about Dilley’s paper, calling him a "QAnon propagandist." It demands that she "retract" the posts, as well as a comment on his Cicada LLC’s BIZAPEDIA page calling it a "#fraud."

After receiving the letter, Randolph never issued any "retraction" of the posts, but Schoenberger never followed up or escalated the matter. She told The State News she suspects that the letter was "just meant to intimidate me … have a chilling effect so I don’t talk about him anymore." Randolph framed the letter as the latest installment in a years-long "campaign" of "harrassment" against her, starting when she first discussed QAnon and Cicada on her radio show and podcast.

She accused Schoenberger and his followers of "doxxing" her address, calling her job and trying to get her fired, spreading rumors that she’s a "child-trafficking pedophile," and photoshopping images of her being beheaded by Pepe The Frog, a cartoon character that has been co-opted as an antisemitic hate symbol. (Schoenberger either disputes those claims or suggests someone else did them.)

While Dilley is the only recipient of a letter demanding retraction to actually be sued for not complying, Schoenberger told The State News he does plan to follow through on others in the future. Randolph, though, said she isn’t worried. Referencing a media law class she’s taking as part of her undergraduate journalism curriculum, she said, "I don’t even see how he thinks that this is a defamation case on my part … if anything, I feel like I have a defamation case against him."

Another letter was sent to Lisa Derrick, a Los Angeles based consultant, who provides "witchcraft and the occult for business, media, and individuals," according to her LinkedIn profile. The legal letter Schoenberger sent her disputes a series of Tweets and a 2020 interview in which she accused him of raping her in 1979 and 1995, demanding a retraction of the allegation.

A third legal letter was sent to Paula Sue Davis, taking issue with the Indiana woman’s online posts tying Schoenberger to QAnon. The letter also singles out a Tweet by Davis which calls him a "64 year old loser. #stalker #narcissist #felon." (Schoenberger was once convicted of felony stalking but the charge was recently expunged, according to court records.)

A Tweet by Paula Davis included as evidence in Schoenberger's legal letter accusing her of defaming him.

The State News reached out to Davis for comment. Her husband, Jesse Davis, responded, describing a cultish saga between his wife and Schoenberger.

Almost 10 years ago, having just finished writing a book about spirituality, he said his wife was "bored" and stumbled upon one of Schoenberger’s internet puzzles. She soon started communicating with Schoenberger, who "brainwashed" her to believe she would "be reborn and inherit the world's wealth," according to Davis.

"It was Mother Mary cult type stuff," he said, adding that he believes Schoenberger "hypnotized" her using videos of "flashing lights and s— he claims to know about certain musical notes and tones that do things to your brain."

"One day, I’m watching my wife watch a video that he emailed her a link to, saying she had to watch it," Davis said. "She literally slumped over in her chair as if she was totally under a hypnotic spell."

In 2017, Paula Davis suffered a severe mental breakdown stemming from the hypnosis, sending her to a psychiatric facility, Jesse Davis said. Soon after she arrived, he claims the facility received a call from a doctor in California saying she did not need to be treated, rather suggesting that she be sent home with Xanax and noise canceling headphones.

The mysterious caller’s name? "Dr. Tom Schoenberger," according to Davis and a medical file he shared with The State News.

Schoenberger denies that he impersonated a doctor when speaking to the facility. And, while he agreed that his music can cause hypnosis, he disputed that it left Davis in need of psychiatric care.

"My music is something that people do get hypnotized by, just as they get hypnotized by Beethoven and Mozart and Bach," Schoenberger said. "Do I believe that Paula was driven crazy by my music? No, I think she’s an actress and I think she’s putting on a show."

In the years since the alleged hypnotism, the Davis’ have mounted a campaign against Schoenberger. They host Sewertown, a toilet-themed podcast which now dedicates the vast majority of its episodes — each five to seven hours long — to discussing Schoenberger, Cicada and the ties to QAnon.

Since publishing her paper, Dilley has become something of a regular character on the show, frequently commenting, reposting episodes on social media, and sending in questions through the livestream’s chat. She has even appeared as a guest, discussing her research, Schoenberger, and the details of her relationship and breakup with Tafoya.

Schoenberger has derided Sewertown, saying hosts constantly defame him, sometimes while brandishing guns at the camera. Davis, for his part, said the dispute escalated only because Schoenberger "harassed" him and his wife with various claims. He said they have allegedly been subjected to legal threats, attempts to "SWAT" their home, and a visit from Adult Protective Services, reportedly prompted by Schoenberger’s false reports. (Schoenberger either disputes those claims or suggests someone else did them.)

"To me, it’s literally crazy," Jesse Davis said. "My wife has never been the same since all this happened."

"I can’t believe I fell for all his bullshit, but I did," said Paula Davis, adding that she does still believe she was hypnotized by his music.

Well beyond Sewertown and the endless Twitter discussion, these factions’ feud spills out on a slew of podcasts, websites and blogs, bearing enigmatic imagery and varyingly unintuitive interfaces. In foreboding fonts and a deeply-online dialect, Schoenberger’s followers fight with his foes about who "bullycided" who, how Cicada got "gamejacked," who’s being "gangstalked," what criminal charges lie in the pasts of various associates, and how many terabytes of evidence someone really has of their opponent's misdeeds.

The role Dilley has come to play in that odd corner of the web – a sort of character in the labyrinthine saga – is not necessarily a natural station for an academic like her.

After completing her undergrad in cognitive sciences from MIT and doctorate in bioscience from Harvard, Dilley spent almost two decades as an accomplished scholar, teaching at R1 schools, winning large research grants, publishing plenty of papers and achieving tenure at MSU.

She could have continued down that steady path, but chose instead to dive head-first into something different altogether. She did not imagine where that desire would lead her, Dilley said, lamenting the disputes over her paper, relationship with Tafoya, and ongoing feud with Schoenberger and his allies.

After an hours-long interview, The State News asked Dilley if she would do things the same way again — if, taken back to 2020, she would make the same choices.

At first, she repeated the spiel she gave many times during the interview, offering a lengthy explanation of how her conscience compelled her to do the research, the way it furthered the mission of the university, and fit her charge as a tenured scholar.

Then, she took a long pause.

"I would have done it again," she added. "The fact that it’s getting noticed, I think, just speaks to its importance."

Administration Reporter Owen McCarthy contributed reporting.