The world below Michigan State University reveals itself in subtle ways.

The small mirages that distort the cold, winter air above tunnel vents. The warm glow of light that seeps through their metal grates at night. The melted rings of grass, bursting through the otherwise snow-covered ground that surround the heavy lids which mark the boundary between what's below and what's above.

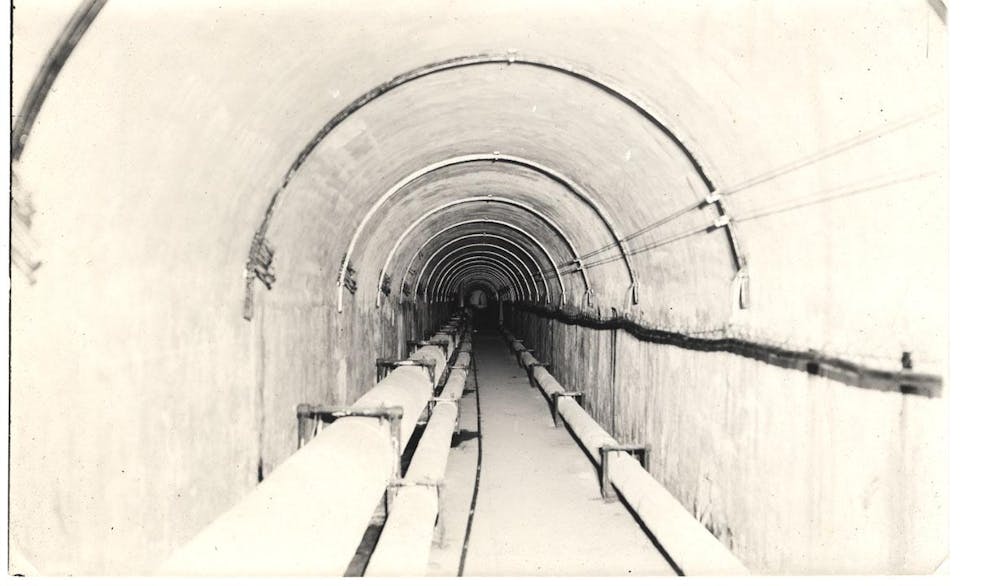

For most of the MSU community, the thirteen miles of steam tunnels under the university present themselves as not much more than a soft rumble of clanging metal and an alluring waft of warm air.

But for the small group of mechanics, urban explorers, indie horror filmmakers, science fiction enthusiasts and private investigators that have descended the depths of campus, the tunnels are not as easily forgotten.

Over a dozen people — from maintenance workers to the spelunkers who hid from them — told The State News what it's really like below the university.

To some, they're the hiding place of criminals and Satanists and the location of emergency bunkers. To others, they're nothing more than an efficient method of transporting steam and power from the university power plant to the rest of the campus. And, for a few, they're a place of refuge, shelter from the cruel world above.

In any case, tales of the MSU underground reveal more about the people telling them than they do about the tunnels themselves, one researcher told The State News.

The truth has been warped by decades of misinformation. One thing is for certain: the tunnels, a massive, dangerous and aging infrastructure, remain an integral and accessible part of MSU folklore.

They first came under the public eye in 1979, when James Dallas Egbert III, an MSU student, was thought to have gone missing during a tunnel voyage gone wrong. His disappearance garnered national attention and prompted an expansive search of the system.

Egbert's case and the lasting infamy of the tunnels helped spur the creation of four books, five movies (two unfinished), a magazine, a series of paintings and countless rumors that circulate among students today.

The university has taken great steps to draw attention away from what's beneath the campus' surface. But despite its efforts, intrigue and a lack of security have kept the student body talking about — and sometimes entering — the world below their feet for decades.

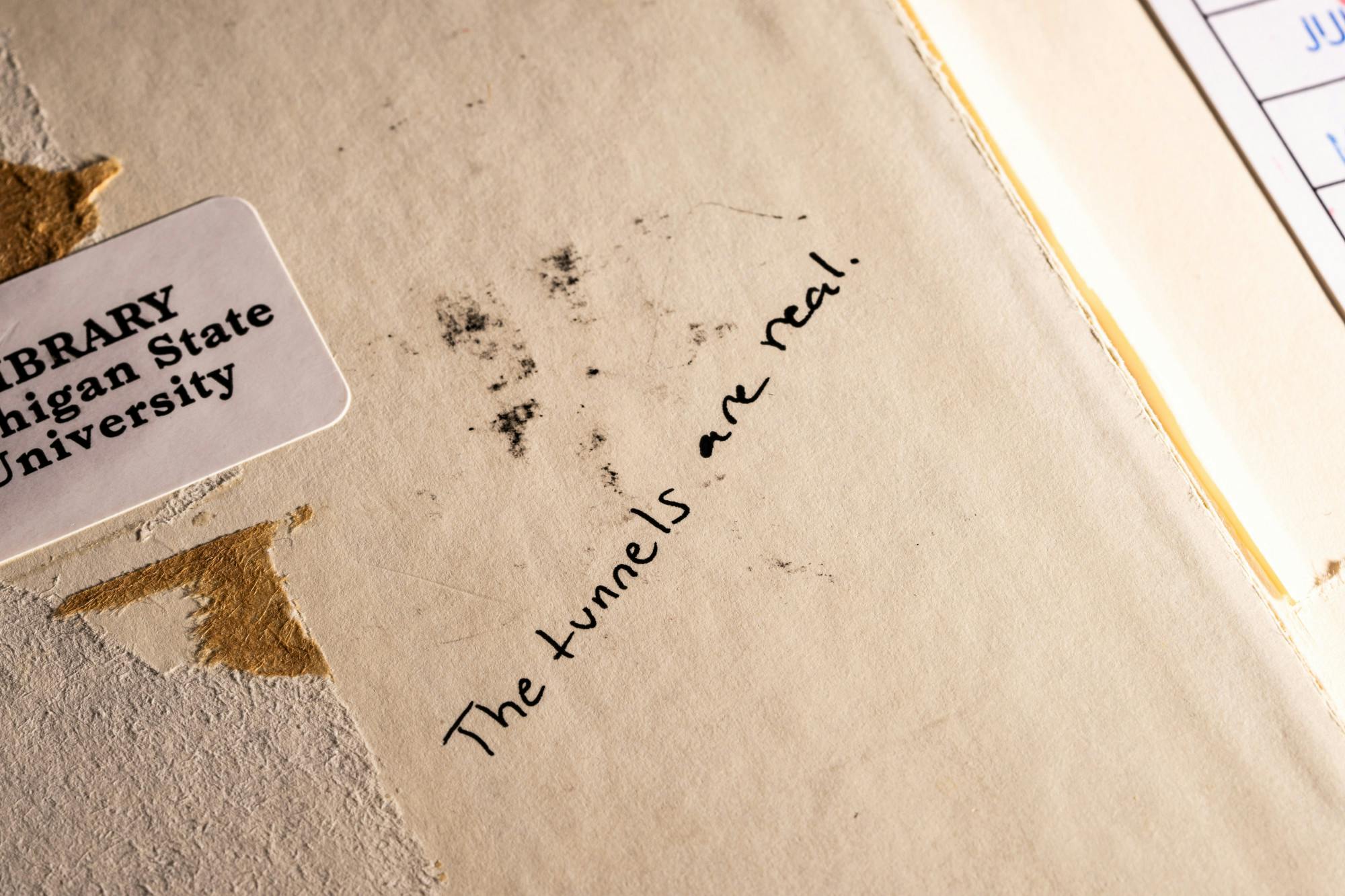

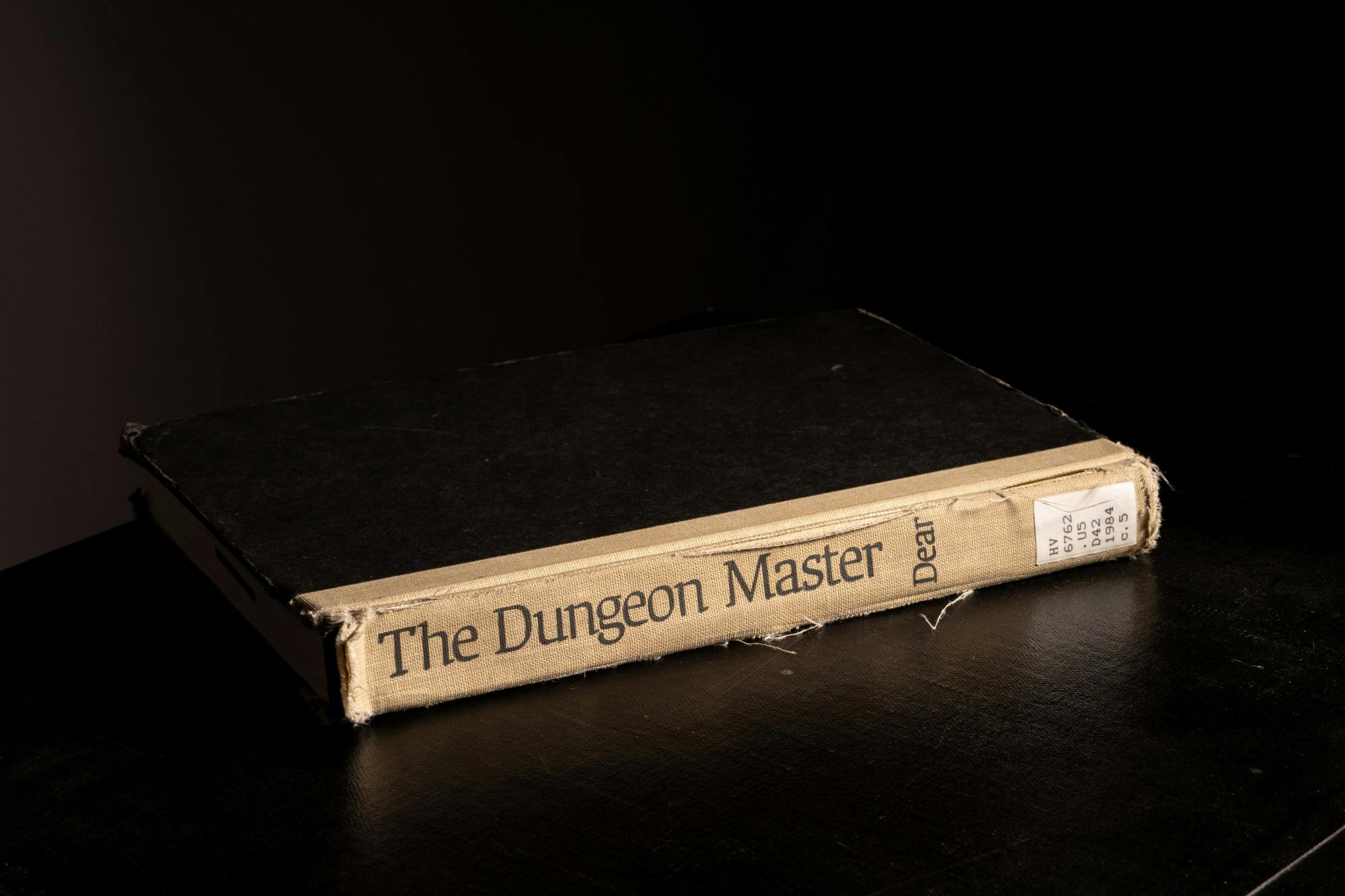

Inside the library copy of the book titled "The Dungeon Master" written by William Dear, a student wrote, "The tunnels are real," emphasizing the conspiracies surrounding steam tunnels that run under Michigan State University. Photo Illustration by Maya Kolton.

Tunneling

While the tunnels were built in 1904, the earliest record of the steam tunnels being used beyond their functional purpose dates back to the 1960s, when it was a hobby for MSU students to explore the tunnels for fun, according to the university archive's online database. They called it "tunneling."

Bob Calverley was one such student.

"What I remember most is that it was dirty," Calverley, who is now an author living in Southern California, said. "It smelled, you know, really kind of funky … It wasn't fresh air by any means."

In 1966, he was taken down into the tunnels two or three times by a classmate who lived on his floor — a geography major who sought to make a map of the network.

"It might be below freezing outside, but you go down there in those steam tunnels, and you'd have to take your coat off and everything," Calverley said.

At the time, security in the tunnels was nearly nonexistent. Even though Calverley's friend was caught multiple times by maintenance workers, "they just warned him not to do it again and told him to get out," Calverley said. "And then he would go back, and, as far as I know, he never got in trouble for it."

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Getting in through tunnel entrances wasn't a problem either.

"It wasn't like it was locked up," Calverley said. "But you had to know where they were."

After Egbert disappeared around a decade later, making national news, that supposedly changed.

MSU said it went to great lengths to prevent students from accessing the tunnels — or even wanting to in the first place.

"The security was dramatically upgraded," John LeFevre, a director and engineer for MSU Infrastructure, Planning and Facilities, or IPF, said.

LeFevre and Scott Gardner, civil engineers for IPF, say they "downplay" the tunnels so that people don't try to get in.

"They're not a desirable place to be," Gardner said. "The steel can be hot. It can burn you; it can hurt you."

LeFevre says increased security, including motion sensors on several tunnel entrances, prevents anyone from getting in unsupervised. A master key is required to unlock any entrance, he said.

"There's only certain places you can get in, and our crews walk the tunnels and make sure it's secure all the time," LeFevre said. "There's no signs that anybody's getting in there anymore."

'The neatest place under MSU'

IPF's current claims echo what MSU told the detective hired to search for the missing Egbert 40 years ago: no one gets in the tunnels who isn't supposed to.

For decades, however, students have told a different story.

While searching the supposedly inaccessible tunnels for Egbert in 1979, private investigator William C. Dear says he saw numerous signs of student activity: beer cans, graffiti, used joints, a table and chairs, and even art projects.

Dear, like many student explorers, didn't have a problem accessing the tunnels. Before MSU granted him official permission to search the network for Egbert, he had been able to get into the tunnels on his own to have a preliminary look around.

He said the tunnels connected every building, something MSU didn't like to admit at the time.

"I don't care what the university wants to say," Dear told The State News. "I gained access to nearly every dormitory."

When the Egbert case made national news, MSU promised the community it would seal off the world below.

"They made a statement that they were going to have the welders come in and weld everything, you know, so they couldn't gain access," Dear said.

But that didn't stop the explorers. Students kept tunneling, even after the Egbert case ended.

MSU alumnus William Blake Hall recalled tagging along with a group of friends from the MSU Science Fiction Society, or MSUSFS, once on a voyage into the tunnels in the early 80s.

"I did not care for it very much," Hall said. "I bumped my head."

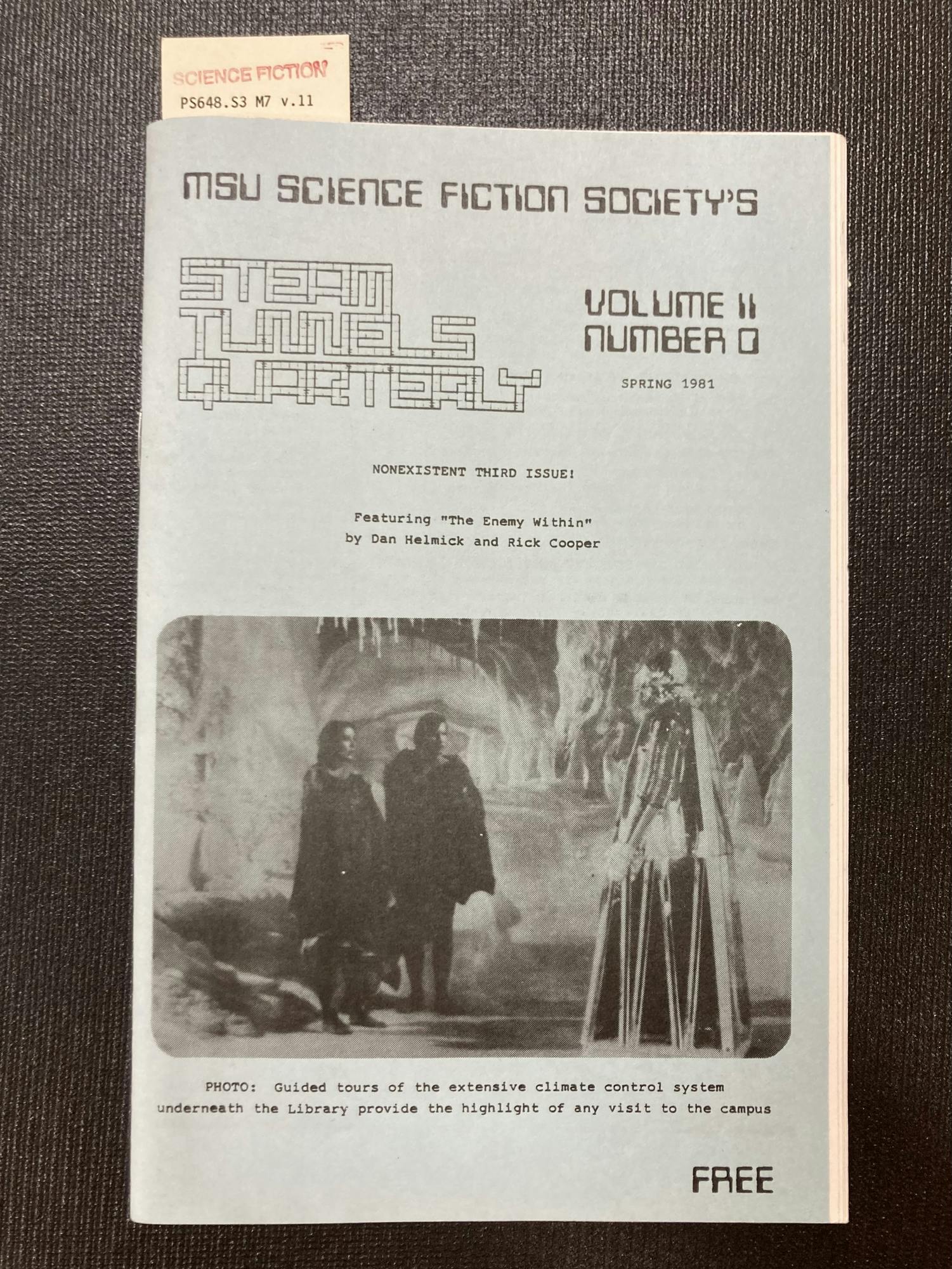

Hall was a contributor to "Steam Tunnels Quarterly," or STQ, a publication run by the science fiction society. He said the name was a joke and not an homage to the underground network.

While STQ was largely dedicated to showcasing MSUSFS members' work, the magazine offers further proof of the tunnels' popularity among subgroups.

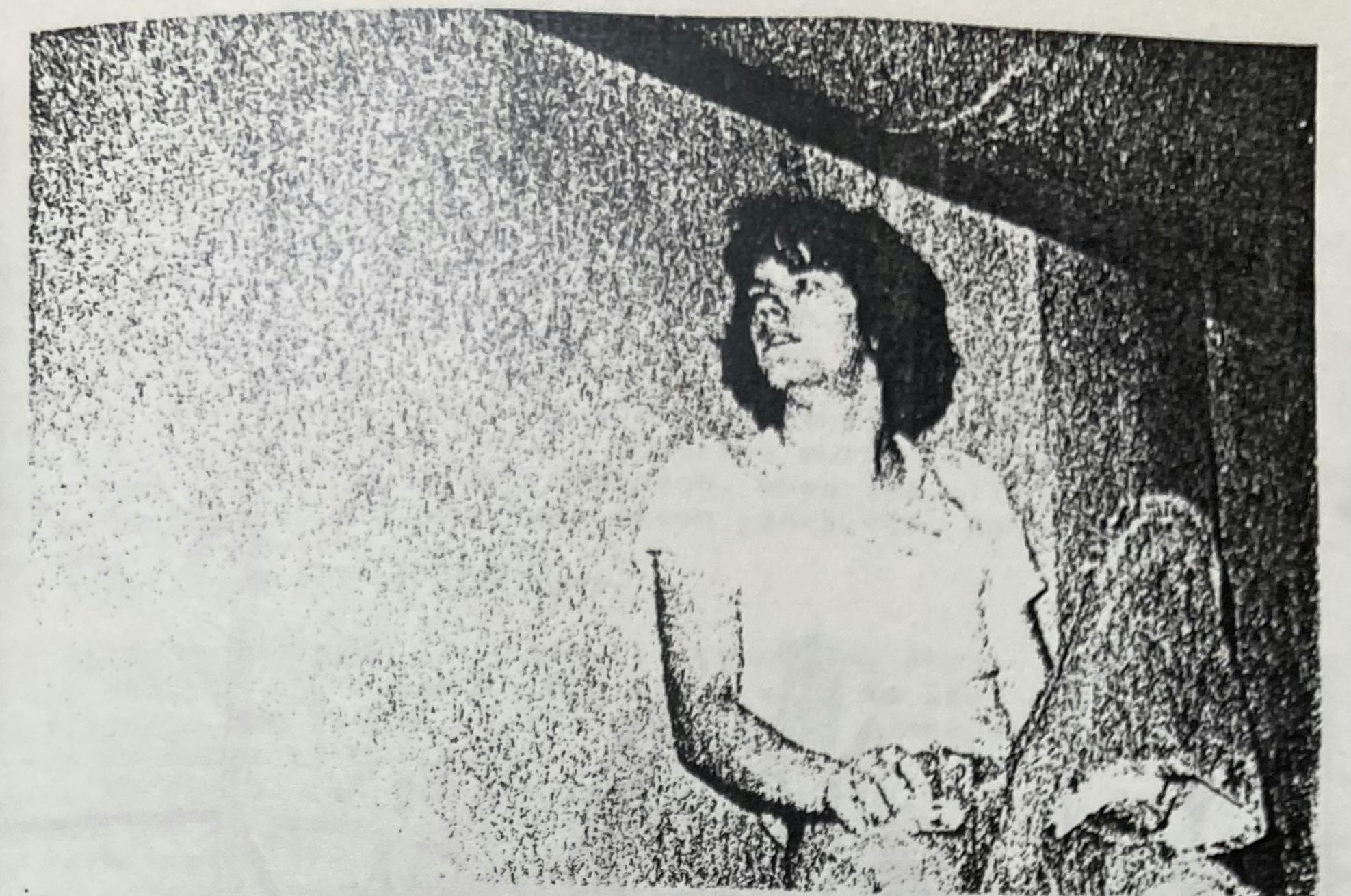

Their 1981 issue ran a picture of editor Larry Farmer leaning against a tunnel wall.

Larry Farmer, editor of Steam Tunnels Quarterly, pictured in the steam tunnels below the Michigan State University library. The photo appeared in the spring 1981 issue of Steam Tunnels Quarterly.

"The photo was taken last year underneath the Library, near the entrance to 'The Maze,'" the caption reads. "By far, the neatest place under MSU; and I would recommend it highly, if steam tunneling wasn't illegal."

Although less documented, exploration of the tunnels continued in the 21st century.

In 2015, five males were arrested for entering the steam tunnels, according to police records obtained by The State News.

Then-MSU police officer Barbara Reblin wrote in the case report that officers were walking around the south side of West Akers Hall when they observed a student climbing out of a steam tunnel. They told the suspect to get on the ground as three more males climbed out, with one more remaining in the tunnel and refusing to exit "although he was directed to several times," according to the case report.

He eventually exited, and all five were cited with ordinance violations.

"All five of the subjects indicated they went in the tunnels out of curiosity," the report states. "The subjects apologized for their actions."

But there’s no better evidence of tunneling than online, where MSU students and alumni continually brag about voyages into the network.

"I have snuck into those tunnels before it's not easy but all worth it," wrote one social media user.

"It is small and smelly," wrote another.

"Some spots got pretty tight … but we persevered and popped out in a few different places in the music building and the library, surprising a few girls in the process," wrote another. "We showed up to a keger later that night all dusty and had a great story."

Dear, the detective, said it doesn't surprise him at all that students are still able to access the tunnels.

In fact, he traveled back to East Lansing in 2013 to prove to an unnamed media outlet that the tunnels were there and still accessible.

He said he easily got in through the same entrances MSU promised it had locked up after Egbert disappeared.

"I gave (the media outlet) an escorted tour around," Dear said.

Tunnel security

It's unclear whether MSU students have gone tunneling in recent years. If so, they haven't been caught. The MSU Department of Police and Public Safety didn't arrest anybody for unauthorized tunnel entry in the fall 2023 semester, according to a public records request.

But whether or not students still explore the world below MSU, the tunnels are certainly still accessible and unmonitored — contrary to what MSU claims.

Multiple MSU employees told The State News there are motion sensors positioned at tunnel entrances to catch intruders.

But no motion sensors have been bought for use in the tunnels in the last 24 years, according to a public records request seeking purchase orders for such technology since the year 2000. Most motion detection systems last for a maximum of 20 years, but hotter temperatures and humidity can decrease lifespans.

When asked about the discrepancy, LeFevre, who insisted the motion sensors existed and have worked in the tunnels before, said he and Gardner had "given all the information that (they could)."

"We don't have any firsthand knowledge of the items you bring up below, nor do we want to speculate on them," LeFevre wrote in an email to The State News.

LeFevre also said IPF makes sure to "secure the lids" to tunnel segments.

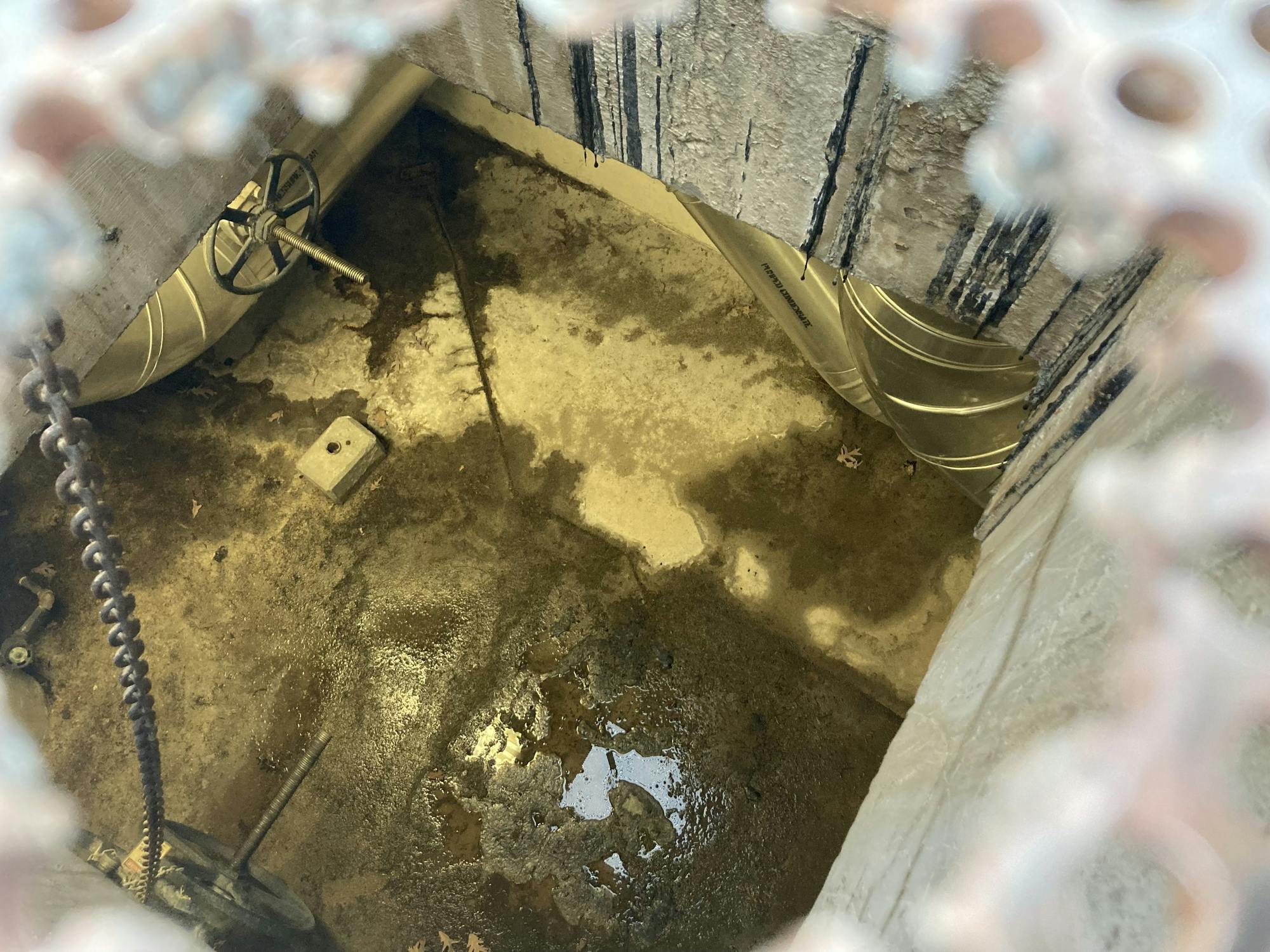

But The State News found multiple unlocked entrances to the tunnels, all in heavily trafficked parts of campus.

Two entrances in the basement of a residence hall were left open all day long, for weeks, while construction continued nearby. A trampled plastic cup and wrappers laid at the bottom of the stairs that lead into the tunnel.

An entrance to the steam tunnels left open in the basement of a residence hall on Feb. 7, 2024.

LeFevre said the open entrances likely lead to small, room-sized vaults that are not attached to the tunnel system but instead where buried pipes can change directions. Such vaults are not locked down, LeFevre said.

But a map of the tunnels and buried pipes, dated 2009, showed no direct buried pipes near any of these open entrances.

It's a violation of MSU ordinance 15.09 to enter the tunnels without authorization.

"No person shall enter any steam tunnel, mechanical room or boiler room unless required to do so in the proper performance of assigned University duties," according to the handbook.

Violating an MSU ordinance counts as a misdemeanor, which can result in a fine and/or imprisonment.

James Dallas Egbert III

At the center of the lasting curiosity surrounding the tunnels and the status they hold in MSU mythos is James Dallas Egbert III.

Though he was the one to bring the tunnels national attention, Egbert's story has been slowly warped and misinterpreted in the decades since.

Egbert, after venturing into the tunnels, "got lost in them and overheated and died," one social media user asserted.

Kent David Kelly, a researcher who wrote a book reanalyzing the case, reported another common rumor, "Facing a slow and horrible demise in the endless dark, he committed suicide. Or, he was murdered by a conspiracy of Lucifer-worshipping gamer-cultists who silenced him to keep their secret safe."

The truth is more complicated, according to a book Dear wrote recounting his time on the Egbert case.

Enrolling at MSU in 1978 at just 15 years old, Egbert was considered a child prodigy. But the boy quickly developed an appetite for danger.

A skilled chemist, he often stole chemicals from campus laboratories to make his own narcotics. He also went "trestling," an activity popular at the time among college daredevils, where students would lay under an elevated train track and let a train pass inches over their bodies.

But one of his most enduring pastimes involved playing Dungeons and Dragons, or DnD, in the miles of steam tunnels below MSU's campus.

DnD, a fantasy role-playing game, is designed to be played sitting down, usually at a table. But for many campus thrill seekers and science fiction enthusiasts, the tunnels provided a more immersive setting.

The person coordinating the game — known as a "Dungeon Master" — would hide artifacts for players to find and engage with in the depths of the tunnels, from soggy spaghetti to rotting meat.

Egbert joined one of the several groups that would play in the tunnels. But, he was soon kicked out because he appeared to be on drugs, and other group members were concerned by how young he was.

DnD and Egbert's involvement in the MSU Science Fiction Society were about the only interactions he had with his peers. And even then, many in his already small circle found him annoying and hard to be around, according to Dear.

Egbert had been suffering from what Kelly described as a "complex interweaving of many psychological challenges and emotional problems."

He felt pressured by his parents to do well in school, alienated by his peers, and was facing drug addiction and confusion over his sexual orientation. He was "a brilliant mind trapped in a child's body," Kelly wrote.

The tunnels were a place of refuge for Egbert, even after his DnD adventures stopped. He sometimes made multiple voyages into the network per day.

On Aug. 15, 1979, he dropped down into the tunnels from the basement of Case Hall. He made his way to a small, private alcove, sat down and lit a joint.

Laying in the hot, dark tunnels, the isolation swelled. He'd later tell Dear how his mind circled around the problems plaguing him — his family, his grades, his sexuality.

He decided to take the Quaaludes — hypnotic sedatives popular at the time — that he had brought with him, swallowing them with milk before quickly passing out.

It was the last time Egbert was in the tunnels.

Back on the surface, his family grew concerned as time passed without hearing from their son.

In the State News archive, a reporter named Micheal Stuart writes a piece about James Dallas Egbert III, a socially-awkward child prodigy who was thought to have gone missing in the tunnels four decades ago. In the article Micheal wrote, James had only been missing for two days. Photo Illustration by Maya Kolton.

After a week went by without answers to his whereabouts, they contacted Dear, hoping he could do what local police so far couldn't: find Egbert.

Dear, who often describes himself as "the real life James Bond," flew to Michigan after a teary phone call from the couple. He immediately began probing Egbert's personal life, talking to anyone who knew him.

"He was certainly not an attractive young man," Dear said. "The only people who were friends with him were people that might be in the same (social) category as him or people who wanted to use him. And I felt like he got used a lot."

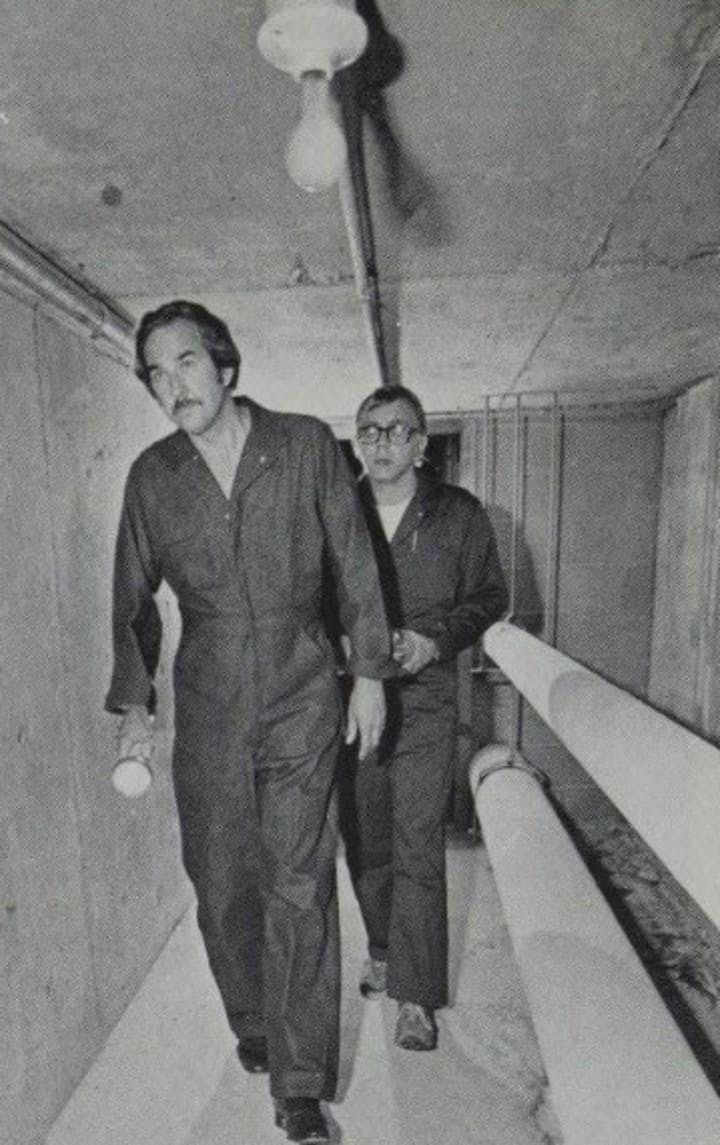

After Dear learned of Egbert's excursions into the tunnels, he asked MSU to let his team formally search them.

But the university denied Dear access, claiming it was impossible to even get in.

The detective knew that wasn't true. Dear and his team had found open entrances across campus, connecting every building.

After another tense meeting, the reluctant MSU administrators conceded and gave Dear, his colleagues and local police permission to conduct the extensive search of the labyrinth.

His team spent days searching the tunnels. Dear earned minor burns from a surprise steam release and a hole scorched through his shirt by a slowly warming metal clip on his overalls.

"I was very tall at the time; I was 6'3", so I had to be careful," Dear said. "I had to duck my head."

Dodging burning hot pipes, Dear spent hours traveling below campus trying to find any sign of the missing boy. He eventually stumbled upon a room — one that didn't appear on the maps MSU had given him — that appeared to be where Egbert and others played fantasy role-playing games.

It was fitted with a table and chairs and "a paper-mache type of figure" in the shape of a man, Dear said. He never learned what the figure was for, or how the table was able to fit through the small tunnel entrances.

Another alcove contained the milk carton and discarded joint Dear would later learn belonged to Egbert.

But the boy himself was nowhere to be found.

The underground voyage futile, Dear also attempted to get inside Egbert's mind.

He played an intense and lengthy game of DnD with local enthusiasts — on land, not underground — to better understand its allure.

In a more daring feat, he also tried to "trestle" at Egbert's go-to train tracks a mile through the woods from campus.

But as the rattle of the tracks intensified, Dear realized the approaching train was fit with a low-hanging grate meant to deflect objects in its path. Inches from death, Dear jumped off the trestle and into the river below.

But despite his intrepid pursuit, the big break in the case only came when Egbert himself called Dear on the phone, not from the maze where he disappeared but alive and well — 1,100 miles south in Morgan City, Louisiana.

Egbert had, in fact, survived the overdose and crawled out of the tunnels. He bounced around between a few East Lansing hosts before deciding to skip town altogether. He made it to Louisiana before contacting Dear, who he had heard was searching for him.

After a few calls, Egbert revealed his location, and Dear quickly came to the rescue.

He confessed everything to the detective: the trestling, the drugs, the struggles with his sexuality. Egbert begged him not to tell the press.

Soon after, Egbert would be reunited with family and Dear closed the case. But that wasn't the end of their relationship, according to Dear.

In the months after he was found, Egbert and Dear had a series of increasingly somber phone calls as the boy's relationship with his family grew even more strained.

On Aug. 16, 1980, a year and one day after he went missing, Egbert fatally shot himself.

"He called me before he died and told me, 'Things didn't change, Bill,'" Dear said. "'They haven't changed at all.'"

Egbert's legacy

In 1984, Dear published The Dungeon Master, a book detailing his time on the Egbert case.

He flew back to Lansing for a book signing. He later sought to make a movie out of the experience. It never got past the screenplay.

"A couple of years back, I spoke to Charlie Sheen about playing my part, but I think he is busy right now," Dear wrote on social media in 2013.

A separate movie deal, set to star Robby Benson, who voiced the beast in "Beauty and the Beast," as Egbert, also fell through, according to Kelly.

William Dear, the detective of James Dallas Egbert III case back in 1979 wrote a book named "The Dungeon Master" discussing the case. James Dallas Egbert III was a socially-awkward child prodigy who was thought to have gone missing in the tunnels four decades ago. Indeed, Egbert made a suicide attempt in the tunnels, managing to survive the overdose and eventually escaping a day later. Investigators dedicated weeks to locating him within the tunnels. His story has significantly influenced the public's perception of the tunnels and the rumors that circulate about them. Photo Illustration by Maya Kolton.

Egbert's disappearance in 1979 came amid a national growing fear of role-playing games, with rampant fear-mongering falsely linking games like DnD with the occult. Religious tracts warning against their devilish effect were spread far and wide.

Media coverage of Egbert's disappearance and death played into those narratives, focusing heavily on his connection to DnD.

Several newspaper articles described the game and its players as cult-like, and many more claimed Egbert was so involved in playing DnD that he couldn’t tell apart reality from fiction, leading to tragedy in the tunnels.

The Egbert case also inspired the 1982 movie "Mazes and Monsters," which starred Tom Hanks in his first lead acting role.

Hanks, playing a college student at the fictional Grant University, gets overly involved in a role-playing game with his friends. The line between reality and make-believe blurs, and eventually Hanks' character tries to jump off the World Trade Center to advance in the game.

Backlash from the media hysteria surrounding Egbert’s case even caused the type of live-action role-playing that Egbert took part in in the tunnels, known as LARPing, to be banned from several major table-top gaming conventions, according to Kelly.

Steam Tunnels Quarterly, the publication from MSUSFS, occasionally parodied these fearful reactions to tales of the tunnels.

The cover of their Spring 1981 issue features an image from the cult-classic science fiction series "Logan's Run," satirically labeled as "guided tours of the extensive climate control system underneath the library provide the highlight of any visit to the campus."

The issue's opening editorial discussed Egbert's then-recent death, arguing that "sensationalistic media coverage of his disappearance had no small role in leading him to it."

"My opinion is substantiated when, the day following (his death), the papers come up with an interview with one of his 'friends,' who claims she foresaw his death in a Tarot reading," editor Dan Helmick wrote.

Fear of the underground

Will Hunt, author of a book on society's fixation on underground and hidden places, said it's common for people to project their fears onto the world below.

"Whatever is frightening to a given community, or whatever they fantasize about in positive and negative ways, that story is told about subterranean places," Hunt said.

The MSU tunnels have similarly been a source of conspiracy. In 2003, biological sciences junior Audrey Brockhaus told The State News she saw "men in suits" walk out of a tunnel entrance.

Two decades later, Brockhaus, now a systems analyst at Arizona State University, still recalls the memory with amazement.

Brockhaus says "a gaggle of men" — she estimates around eight — crawled out of a tunnel entrance near the administration building, one by one, wearing gray and blue business suits.

"My first instinct was, 'Don't let them see you looking at them,'" Brockhaus said. "So, I was trying not to stare at them, but I was just like, 'They just came out of the freaking ground!'"

Before then, all Brockhaus knew about the tunnels was that they were "small and damp" and inhospitable. Seeing the mysterious men made her question that.

"How uncomfortable could it be down there if these well-dressed men, in the middle of the day, are going down there for some reason?" Brockhaus said.

Brockhaus said she doesn't have enough information to properly explain what she saw, but she still wonders if there's "some kind of contingency" in the tunnels that MSU wanted to show the men.

"It almost seems like it's a bomb shelter they don't want us to know about, like a weird backup plan for a nuclear war or something," Brockhaus said in 2003.

MSU spokesperson Emily Guerrant said she was not aware of any emergency plan involving the tunnels.

Jeff Burton, a local horror filmmaker, believes the underground naturally invites fear.

"It's the unknown," Burton said. "Could there be paranormal activity down there? Could there be some weird … nocturnal, cannibalistic organization underground? It can hit people in completely different ways, and that's what you want."

Burton uses that mystery to his advantage. He filmed two movies — "Terror at Baxter U" (2003) and "Acts of Death" (2007) — partially in the MSU tunnel system.

In "Terror at Baxter U," a man-eating creature with a taste for blood dwells in the steam tunnels below the fictional Baxter University. The monster is based on the 'chupacabra,' a vampire-like cryptid whose name means "goat-sucker" in Spanish.

In "Acts of Death," a school theater group uses the tunnels to access their theater/hang-out spot after hours. When a perverted hazing ritual goes wrong, the students use the tunnels to hide the body of their classmate. A witness to the crime is later sliced in half as she climbs down the ladder of a tunnel entrance, attempting to escape a murderous revenge seeker.

The filmmakers were not allowed to indicate "Terror at Baxter U" had anything to do with MSU, and the cast and crew had to go through "tunnel training" before filming began.

"It wasn't like they just said, 'Yeah, off you go, have fun,'" Burton said. "We went through different health things, they wanted us to to spend like 30 minutes down there to make sure nobody was going to have a panic attack, and then it was fine."

IPF also warned the crew of bat guano, though Burton said he didn't see any bats while filming.

Despite the natural urge to associate the underground with mystery and terror, Burton's films did not have the fear-inducing effect he had hoped for.

One reviewer advised to avoid "Acts of Death" at all costs and several claimed "Terror at Baxter U" was the worst movie they'd ever seen. After an early premiere in 2002, a reviewer for The State News called the film "just plain bad."

"One review said, 'Spend your two dollars on a Whopper Junior,'" Burton said. "'You'll be more satisfied.'"

Criticism has left the filmmaker unfazed.

"To any one of those people who decided they wanted to become a critic: I'm happy to see you do it," Burton said.

A place of refuge

Not everyone fears the tunnels. Some even embrace them.

Calverley, the man who went tunneling in the '60s, envisioned them as a place of safety and protection. He incorporated the MSU steam tunnels into his 2012 novel "Purple Sunshine," drawing from his own experience exploring the network as a student.

In the book, Gloria, a pregnant musical savant, takes shelter in the MSU steam tunnels while on the run from a murderous pedophile stepfather, a crime family and the police.

She lives in the tunnels for days at a time, sleeping on stolen cushions and blankets tucked out of view of maintenance workers.

Not unlike Egbert, who used the tunnels as a temporary escape from the harsh world above, Calverly said Gloria "certainly feels safer down there than she would outside."

Hunt, the underground researcher and author, says the underground can sometimes offer an opportunity for transformation.

"It allows you to transform, to take on a new identity," Hunt said.

Stories of such transformation have been recounted throughout world mythology, from the Epic of Gilgamesh to Native American legends, Hunt said.

"You have stories of people going into dark, remote caves and becoming lost traversing a dangerous landscape, and then reemerging as a person who's undergone a transformation," Hunt said. "It might seem silly to think about a system of steam tunnels under a state university in the same way, but I think it is (the same)."

It's easy to see why Egbert's story is now a part of MSU mythos, Hunt says.

"He went into this dark, perilous underworld and re-emerged … a legend that people were still talking about," Hunt said.

Those who work in MSU's steam tunnels take a less creative view.

When asked about the university's history of tunneling, Gardner, the civil engineer, laughed.

"Dungeons and Dragons, you mean?" he said. "Yeah, I've heard of it."

He emphasized that he tries not to romanticize the tunnels so that students aren't encouraged to try to get in and potentially get hurt.

Michael Lark, who works in MSU's telecommunications department, says the tunnels don't live up to local lore.

He first heard about the "Dungeons and Dragons thing" in high school. Now, a technician who services communication wiring in the tunnels a few times each year, Lark says it's far from the "dirty dungeon" people make it out to be.

"I think it has this misconception of these crazy tunnels that run from castle to castle," Lark said. "It's just a place where we can run utilities to service campus."

He believes students would only try to get into the tunnels "for the clout."

"It's more of just a story a student can tell or for bragging rights," Lark said.

History of MSU's underground

In the 19th century, buildings on campus were lit with oil lamps and heated by wood stoves, according to historian Stephen Terry in his book on MSU history. These antiquated methods led to a series of fires, which prompted the university to seek new technology for heating and lighting.

The solution, in 1904, was to build a power generation and heating system at what is now the Hannah Administration building. Steam tunnels ran in all directions from the plant, dispersing steam, water and power across campus.

In 1948, MSU moved the power plant elsewhere, and as new buildings were added, new steam tunnels followed. Many tunnels still converge under the administration building.

As the tunnels aged over the next century, severe structural cracks threatened the heating and electricity of many nearby buildings. In 2011, IPF began massive renovations of sections of the steam distribution network in the West Circle to combat this deterioration. The project lasted years.

In 2015, workers were digging up a portion of the hundred-year-old steam tunnels in the parking lot in front of the MSU Museum when they found an even older piece of MSU history.

When workers unexpectedly hit brick, the Campus Archaeology Program, or CAP, fled to the scene.

The program, which consists largely of MSU students, aims to preserve and uncover buried university history. When MSU breaks ground for any sort of construction, it makes sure CAP has a chance to dig for potential artifacts.

Near the historic tunnels, CAP found pieces of a porcelain doll. They glued the shards together to create Mabel, who was thought to have been manufactured over 160 years ago.

"The reason we think she probably ended up there is either she got broken, or a sibling was being a jerk and threw her in there," Stacey Camp, the current director of CAP, said. "Who knows. But she's pretty remarkable, because she would have been expensive. She's got hand-painted hair, hand-painted eyes, beautiful lips and cheeks, you know, just gorgeous."

CAP discovered Mabel at the top of a nearly 200-year-old outhouse, or "privy," where students and faculty in that area of campus would relieve themselves in the 1860s. Privies were often topped off with a layer of trash and unwanted items once they were full with excrement, creating a treasure trove of archaeological materials centuries later.

"So yeah, we put ourselves in a lot of kinda gross situations," Camp said.

Camp doesn't like to talk directly about the tunnels, though her team worked closely with them during IPF's West Circle renovations.

But she shares a fascination with what's buried in MSU's soil. She thinks about the layers of history under her feet "all the time" as she walks through campus.

A tale of two Tunnel Bobs

Fascination with the underground is not unique to MSU.

Where tunnels go, explorers follow. Since steam tunnel systems can be found under most large universities, a rich history of tunneling is present across the nation.

The steam tunnels underneath the University of Michigan's campus. Courtesy of "Tunnel Bob."

Hunt, researching for his book, once followed a group of student tunnelers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, or MIT. They called themselves "hackers."

"They took me into a network of tunnels, and duct ways, and different types of passages and hidden spaces throughout campus," Hunt said. "We spent a whole night … moving through an invisible plane that connected all the buildings on the campus."

When a hacker makes their way into a hard-to-reach space, they sign their codename on the wall. One student, under the alias "Socrates," was famous for reaching the most hidden parts of MIT's tunnels.

"You'd think you had reached a place that was totally invisible, totally beyond reach, and there was sort of evidence of this legendary character who had already been there," Hunt said.

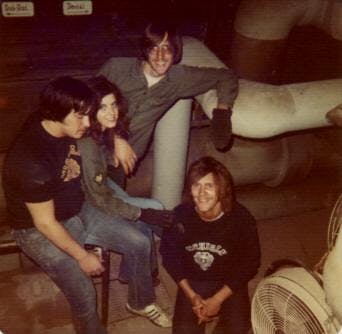

A similar troglodyte gained fame at the University of Michigan in the early 1970s. A security guard named him "Tunnel Bob" for his many excursions into the university's steam tunnels.

Tunnel Bob, now a professor at the University of California Berkeley, requested his true identity continue to remain anonymous.

Tunnel Bob described the tunnel system as a known secret at UM – one he wasn't in on until "a couple of stoner-looking dudes" popped out of a tunnel entrance in front of him and a roommate.

"They were like, 'Hey, dude, can you tell us where we are?'" Tunnel Bob said.

It turned out the explorers had traveled from the opposite end of campus via the university's steam tunnels.

"That's when we decided we ought to go down there," he said.

Thus began two years of exploration, mischief and close encounters with the police. Tunnel Bob would venture into the tunnels a couple of times a month, often bringing friends.

"Tunnel Bob" and his friends pose while exploring the University of Michigan's network of steam tunnels in the 1970s. Courtesy of "Tunnel Bob."

In one section known to explorers as "Hole in the Wall," the UM tunnels gave access to a medical storage room.

"They had all these fetuses floating in big jars of formaldehyde liquid, with ultraviolet lights," Tunnel Bob said. Spray-painted directions to the destination were placed throughout the tunnels.

But Tunnel Bob’s legacy is defined by a cold day in April 1975, when he and his friends found a valve hidden in the depths of the network.

It was accompanied by a warning: "Attention Workers. Do not turn off this valve. It must be on to have hot water in the President's House."

"Tunnel Bob" and his friends shut off the water to the President's House in the University of Michigan's network of steam tunnels in 1975. Courtesy of "Tunnel Bob."

"Talk about an invitation," Tunnel Bob said.

The group of rabble-rousers proceeded to turn off the president's water, then tunneled to the offices of The Michigan Daily to inform them of their prank.

They got in through a small entrance on the floor of the newspaper's broom closet, but the door was locked from the outside. They ended up calling the offices instead and made the paper's front page the next day.

Now, 50 years later, Tunnel Bob says he's sometimes tempted to go into the tunnels at UC Berkeley, but, being a "grown-ass adult," he never has.

"I guess it never completely gets out of your system," he said.

400 miles west of UM's Tunnel Bob resides Robert Gruenenwald, who gained fame for allegedly living in the 20 miles of tunnels under the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Locals refer to him, too, as "Tunnel Bob." There's no relation between the two figures other than their uncommon interest. UM's Tunnel Bob told The State News they've never spoken to each other.

Rumors about UW's Tunnel Bob run rampant, according to the the Badger Herald. Some say he was a Vietnam vet. Others say he has a mean temper. Some say his fear of women drove him underground.

The gossip is largely unfounded. While Gruenenwald is certainly something of a recluse, UW's Tunnel Bob is just a man who loves the danger and intrigue of the steam tunnels.

He insisted he lived aboveground in an interview with the Badger Herald.

"Wouldn't spend a night sleeping in these tunnels … You would end up dead," he told reporters.

Alex Walters contributed to the contents of this article.