In 1940, the horror film "Son of Ingagi" was of its kind to feature an all Black cast. A little over 80 years later, Jordan Peele has become a leading name in Hollywood and the Black horror genre, which has become mainstream in the past decade.

That change didn’t happen out of nowhere, though, and it certainly didn’t happen overnight.

Michigan State University Audrey and John Leslie Endowed Chair in Literary Studies Dr. Kinitra Brooks is seeking to fill in those gaps, all while salvaging what the genre lost along the way.

Brooks' research includes topics like Black women’s role in Black horror films throughout the decades to Afrofuturism and how conjure women show up in literature and science fiction.

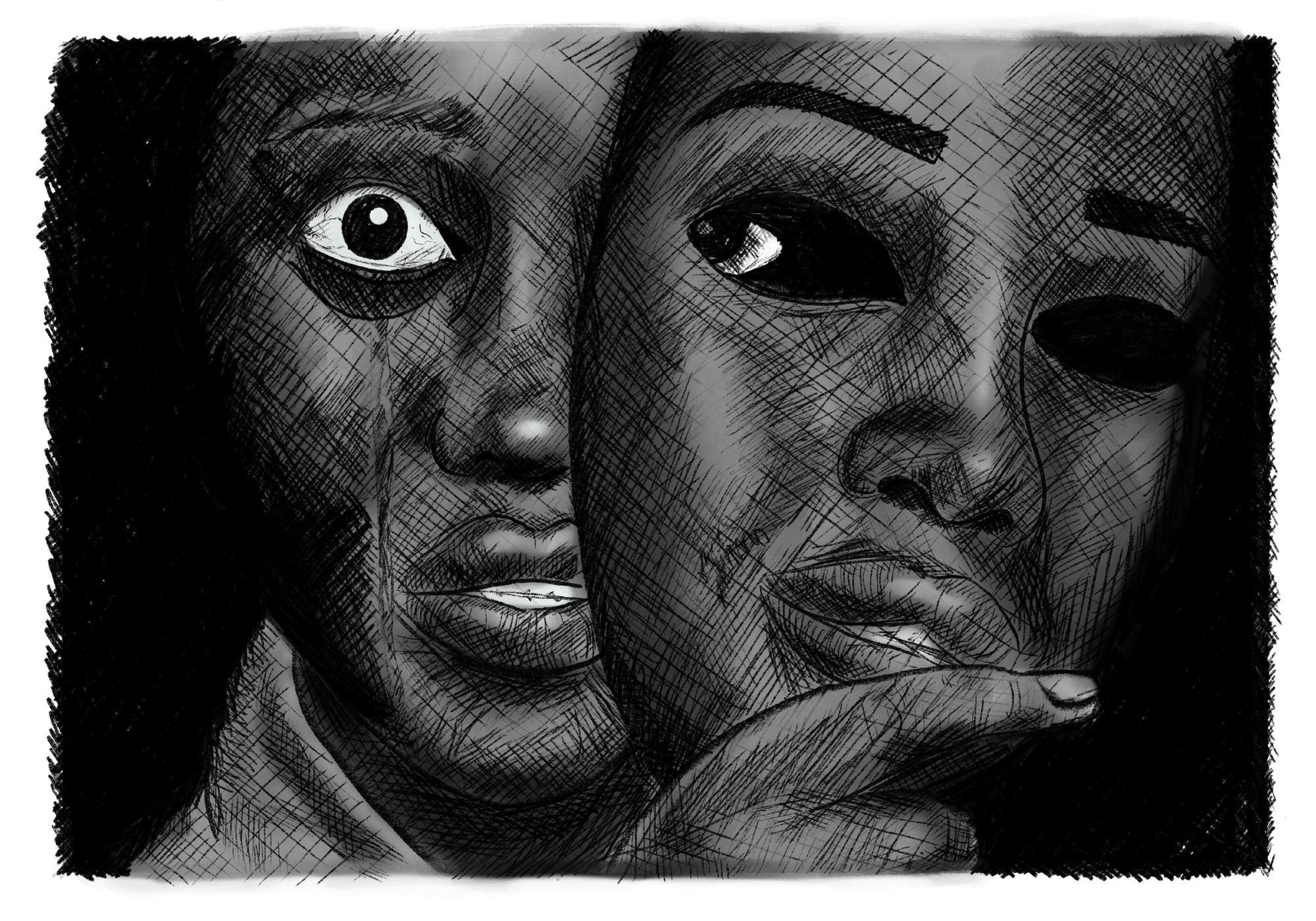

For a long time, especially in early cinema, Black people were viewed as monstrous or something to be afraid of, Brooks said.

According to Brooks this viewpoint has changed over the years, especially in the early 1970s during the "Blaxpoitation" film movement.

Although the movement can be considered controversial, Brooks said, it began to place Black actors at the center of cinema, including horror films.

She said that in viewing Black protagonists, audiences began to see who the monster was from Black characters' point of view, thus complicating the narrative at the time.

And when it comes to the horror genre, so much of what is portrayed in mainstream cinema is meant to scare the "ideal viewer." Brooks pointed to University of California, Berkeley professor Carol Clover’s definition of the ideal viewer as a white, middle class, heterosexual male.

So when the goal is to scare that type of ideal viewer, Brooks said, it wasn’t uncommon for filmmakers to portray not only race, but also gender and queerness as monstrous.

She found the result was a lack of well-represented Black women in horror films. This is due to the fact that when race is made to be the monster, it’s usually in conjunction with Black manhood, whereas when gender is made to be the monster, it’s made in conversation with white womanhood, she said.

"(Black women) are the other of the other," Brooks said.

This discovery led her to go on a "rescue mission" for Black female characters, as well as how Black women have talked about themselves in horror.

In early cinema, Black spiritual practices became a stereotype, resulting in the villainization of Black women. It wasn’t until later, she said, that Black women began to see those practices as a place of power and use it as a way to change their reality.

A more recent example Brooks used was Beyoncé’s album "Lemonade", the subject of a book she edited called "The Lemonade Reader."

"'Lemonade' is sort of rediscovering the maternal and spiritual practices of her mother's people in Western Louisiana," Brooks said.

Brooks said as storytelling advanced through the years there seemed to be a stark difference in complexity of Black female characters written by Black writers versus non-Black writers. One example can be seen in Jada Pinkett Smith’s character, Jeryline, from the film "Demon Knight," she said.

While Pinkett Smith's character is Black, she’s written in a way where it seems like she just "happens to be Black," and nothing much beyond that.

"She stands in as a Black woman, but her Blackness isn't really spoken about and dealt with," Brooks said.

On the other hand, Brooks used the short story "Chocolate Park" as an example of where the characters’ experiences as Black individuals are actively talked about and included in the narrative.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Dr. Brooks' interest in the absence of Black women in horror eventually served as the basis for her book "Searching for Sycorax: Black Women's Haunting in Contemporary Horror." In it, she compares the effect the unseen character Sycorax from Shakespeare’s "The Tempest" has on the protagonist to the similar roles that Black women have held in horror genres.

"Even though she is absent, her presence is still felt because he's obsessed with her," Brooks said.

However, it isn’t just Black horror that Brooks focuses on. Her research also engages with Afrofuturism, a genre that has recently gained more traction with the release of films like "Black Panther."

Like Black horror, Dr. Brooks said Afrofuturism began to center Black modes of thought and allowed Black people to think about their stories outside of a white lens, which gets audiences and artists alike asking crucial questions about what their present state is, as well as what aspects of the past they want to take with them to the future.

"A lot of my work is the recovery project of the spiritual practices that have been lost, our spiritual practices that have been sublimated," she said.

Dr. Brooks was also featured in the documentary "Afrofantastic: The Transformative World of Afrofuturism" — in which she spoke about the depth and complexity of Afrofuturism rather beyonbd just "Black Panther" or "Black people in space."

"Black folks' futures and futurism within Black communities is something that we all need to participate in," Brooks said in the documentary. "We all have skin in the game."

Discussion

Share and discuss “MSU expert Kinitra Brooks explores representation in Black horror, Afrofuturism” on social media.