By Mary Fogg-Lidel, MSU student

No one tells you just how awkward it is to make eye contact with the person you barricaded yourself with for four hours when you’re walking down the hallway of your dorm, on your way to fill up your water bottle before bed.

You wouldn’t think that you could laugh when you hear over the police scanner that the shooter is in the basement of your building, but you do, when a police officer comes to break down your neighbor’s door and yells at the top of his lungs, “Holy shit there’s a cat in here!”

Somehow, you roll your eyes and smile slightly when your Mom texts you ‘You know I hate those things’ when you tell her that the people you’re sheltering with found an old Breeze pro and are passing it around. You still find it in you to decline it, straight edge as ever.

Beyond the full body terror, the fear and frantic phone calls, on Feb. 13tour world became fragmented. Our lives as a college student collided with that of something new yet known to us as we crouched low, ran fast, pushed furniture against the door and said goodbyes.

A mass shooting is an inhuman, senseless act, but an easily familiar scene to our nation. Violence saturates our experiences, it shuffles in tandem with our daily lives. It is a monotonous tone that’s colored our upbringing, a droning whine in our ears that rises and falls as grocery stores, churches and highschools are named, then forgotten. The familiarity of our situation is the horror of our situation.

Michigan State is not the first, and it is already not the last.

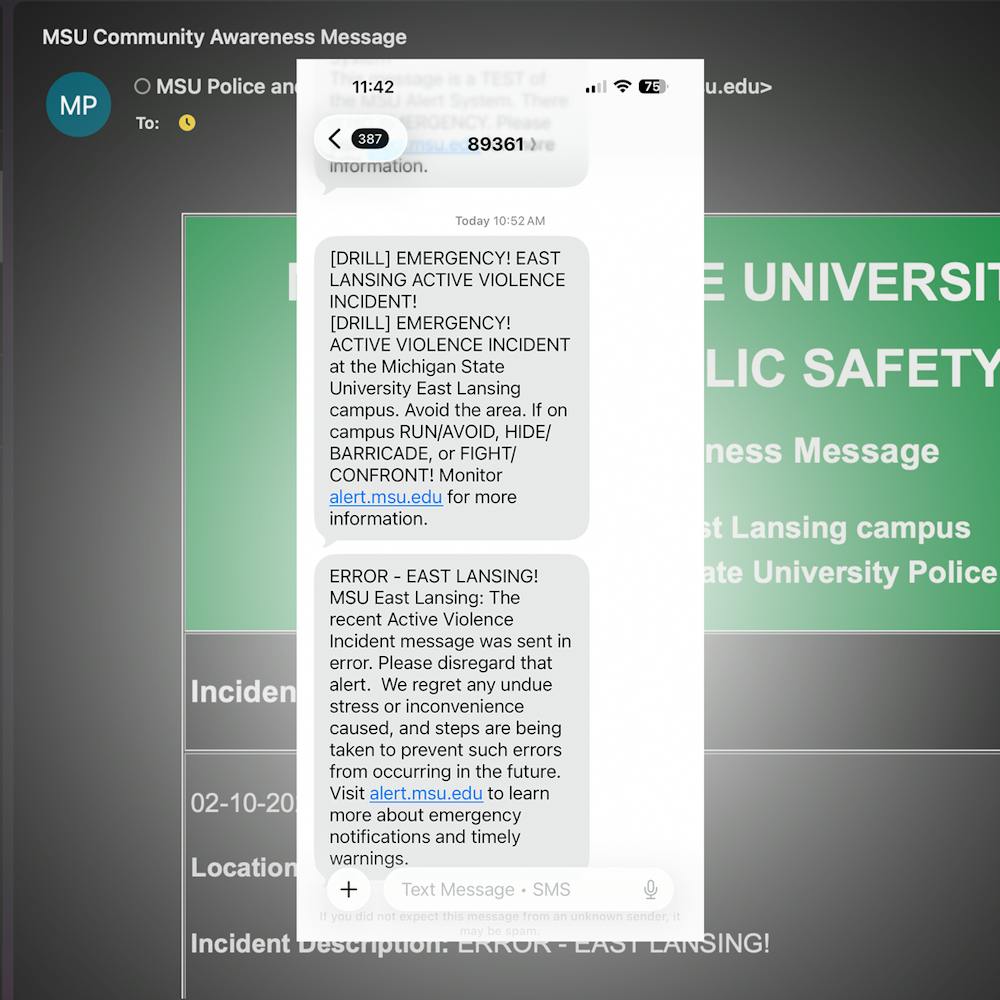

I found myself focusing on the events that passed in the dorm I was sheltering in, the cat, the Breeze pro, my chiding mother, an email notification reminding me to take a quiz sandwiched between alerts of an active shooter. Mass violence married to my average day.

Looking into these small moments made me sit with just how ingrained these awful events are into our lives. I’ve read news about a new gunman casually over breakfast, listened to newscasters describe a massacre as I play a board game with my friends, or see an email detailing a shooting off campus as I finish my homework for the week.

There are no words to describe these tragedies, no offer of comfort is quite correct when you’re made to deal with something so barbaric and purely destructive. Part of the violence is realizing that this has in fact happened to you, that just that morning you were on your way to choose a Valentine’s gift for your loved one. There are no words to describe these feelings, but you can read them.

As students streamed out of my dorm, close to 1:20am at this point, I compared the text messages I sent to my loved ones to those of students from Parkland. What my parents had texted me was there on a grainy phone screen, word for word, as a father urged his son to stay silent in a closet. The girls I was barricaded with feared that there were multiple shooters, and I saw this same worry mirrored in the text messages of a student just a few years younger than myself. There exists 50,000 other texts just like this in East Lansing alone.

There was a great sense of absurdity as I read these messages, of confoundedness that has then turned into anger which hovers constantly over my shoulder. Gun violence is a tragedy of past, present and future. There exists the lives lost, the lives affected and the lives that will end. Fifty-eight percent of American adults know someone or are someone who has experienced gun violence, and will have to continually rewatch, relive, and reread the violence they have lived through. That monotonous drone never quiets as new reports of ‘shots fired’ ring out daily.

Our only hope is to recognize the horror of this familiarity. It is inhuman that these events have become a part of our humanity. It is senseless that we are made to make sense of violence on this scale, and it is barbaric to expect us to live through continual barbarism.

By recognizing the horror of our familiar relationship to gun violence, we can begin to confront its place in our culture. By experiencing this event ourselves, we see the true magnitude and the absurdity of this epidemic.

This perspective is an invaluable one. It is a perspective that holds the weight of grief tightly in its hands, and close to its heart. By experiencing this moment together, something stirs within us collectively — a fierce and unyielding awareness that can't be ignored. In the aftermath of tragedy, we find strength in community and solace in the shared experience of loss. We learn to lean on one another, to hold each other up, and to never forget the lives that were lost.

We carry with us a burden of awareness, the horror of familiarity, but we also bear witness to the power of hope and the resilience of the human spirit. We know that change is possible, that healing is within reach, and that by coming together in solidarity, we can create a deeper and more compassionate understanding of the aftermath of mass violence.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Discussion

Share and discuss “Guest Essay: 'What Feb. 13 taught me about the horror of familiarity'” on social media.