When Jenny Rentfrow was a child, she wasn’t taught anything about her culture.

Rentfrow, who is Anishinaabe, said her grandmother spoke Anishinaabemowin— but refused to speak it in front of her grandchildren.

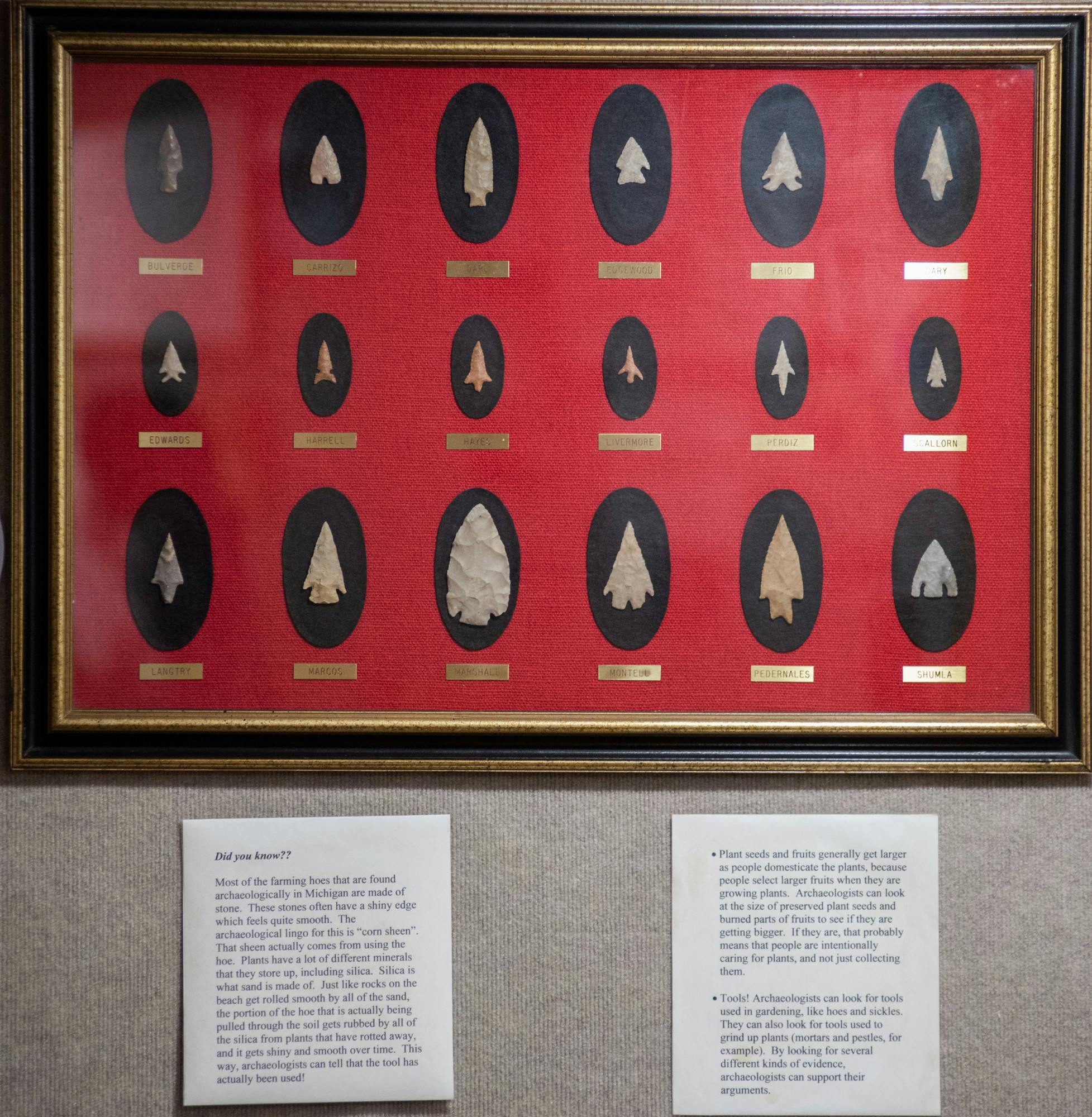

A display at Nokomis Cultural Heritage Center in Okemos, photographed on Nov. 19, 2021.

When Jenny Rentfrow was a child, she wasn’t taught anything about her culture.

Rentfrow, who is Anishinaabe, said her grandmother spoke Anishinaabemowin— but refused to speak it in front of her grandchildren.

“She said, ‘Well, because when I grew up, it wasn’t good to be an Indian,’” Rentfrow said. “Until I was an adult, it was discouraged. It takes a long time to get back from that.”

Nowadays, Rentfrow is a secretary at the Nokomis Cultural Heritage Center in Okemos. She speaks the language, but doesn’t try to hide it. She teaches it to others at a weekly class instead.

According to its staff, the Nokomis Cultural Heritage Center serves two goals: To educate and to preserve.

“Our dual mission is to be here for non-native people or Native people that want to learn about this culture, but also to sort of be a liaison for the Native community in Lansing,” Rentfrow said.

The educational mission mostly takes the form of exposing students to Anishinaabe culture. Before COVID-19, hundreds of children from nearby schools would visit the center, and a paid staff would show them cultural artifacts, teach lessons and take tours in the nearby park.

After an 11-month hiatus following the initial pandemic lockdowns, the center’s staff had to look to alternative methods to educate the students.

Victoria Voges, a curator at Nokomis Cultural Heritage Center, said that they’ve begun doing outdoor, off-site classes more frequently in order to side-step restrictions and safety concerns.

“That actually works better when you have that amount of kids,” Voges said. “They’re missing the experience of the beauty here, but we’re still kind of trying to figure out how ‘Gee, how do we do (the tours)?’”

The outdoors is becoming more a focus for the center’s educational goals in light of this. Rentfrow said putting more emphasis on the nature-related aspects of Ashininaabe culture is making its way into the curriculum.

“That’d be really cool, to develop a sort of lesson outside,” Rentfrow said. “And maybe pointing out some of the plants and animals and stuff that are important to our culture.”

When it comes to the preservation portion of the center’s mission, the staff offer numerous opportunities for Anishinaabe citizens in the area to learn about and practice their culture.

The teaching of the Anishinaabemowin language is a large part of the preservation initiative, and classes are the primary driver behind it.

The classes draw language speakers from across the state, and even into Canada. Recently, speakers from Manitou Island in Ontario joined the group. Rentfrow said that the class size is generally about 15 to 20 people, composed mainly of local citizens.

“Culture is so much tied to language,” Rentfrow said. “The more language I learn, the more I’m just floored as to what you’re missing if you aren't studying the language.”

During the COVID-19 hiatus, the center turned to virtual options to continue its language education. Rentfrow’s classes are currently held on Zoom, and she said it’s allowed her more flexibility in collaborating with other language teachers.

“With the advent of the internet now, we could do so much more,” Rentfrow said. “I can take a language class at 11 o’clock, and from a man up in Traverse City. We have a community of classes, we’ve been together for over a year.”

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Rentfrow pointed out that young Native American citizens in particular have begun to take more interest in learning about their cultural background.

Rentfrow said it’s taken a long time to shake the fears her grandmother’s generation held when it came to practicing Ashinaabe culture.

“I think it's coming back," Rentfrow said. "I think that more and more young people are getting interested in their culture. Wanting to learn the language, wanting to take part in cultural celebrations.”

Voges said that she thinks that people are being more drawn into Anishinaabe and other Native American cultures because there’s been more awareness and exposure in recent years.

“They're being drawn (to) that,” Voges said. “So I think it's gonna happen that it just really flourishes again.”

Though the Nokomis Cultural Heritage Center is back open and interest is at a high, it has been difficult having enough funds and staff to make ends meet.

Grants are the center’s main revenue source, and are the core way the center is able to stay open. Rentfrow said the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act helped the center survive the pandemic, and a recent Michigan Humanities grant is providing them funding for the next year.

“So that's going to keep us open from September through September (2022),” Rentfrow said. “So we're really fortunate to get that. And that kind of is helping us get back on our feet.”

Pre-pandemic tours, gift shop profits and donations use to make up significant revenue streams. However, in the “new normal,” it’s been harder to rely on these, the staff said.

At one point the center had paid employees, but eventually switched to an all-volunteer organization after budget cuts. Rentfrow said that as their budget increases from grants and other revenue streams, they plan on introducing paid positions again.

While it’s been difficult, the staff say that they don’t do it for the money— they simply hope to make a difference.

“It's not the compensation of the money,” Voges said. “But seeing that I've touched and opened somebody's mind and heart.”