Why do people believe what they do?

Americans are prideful people. Stubborn. And most importantly, Americans are right — they always are and have always been. Each of us has been, is and will be right … always.

Why do people believe what they do?

Americans are prideful people. Stubborn. And most importantly, Americans are right — they always are and have always been. Each of us has been, is and will be right … always.

But with over 300 million people living in the United States, how can every single one of us be correct in what we say, do and believe every moment of the day? It’s impossible and overwhelming.

Today, it can be overwhelming to listen to all of your Facebook friends post about how they’re right. If you think you’re right, you get called out for believing in “fake news,” but if you think someone else is wrong, you’re calling them out for believing in fake news.

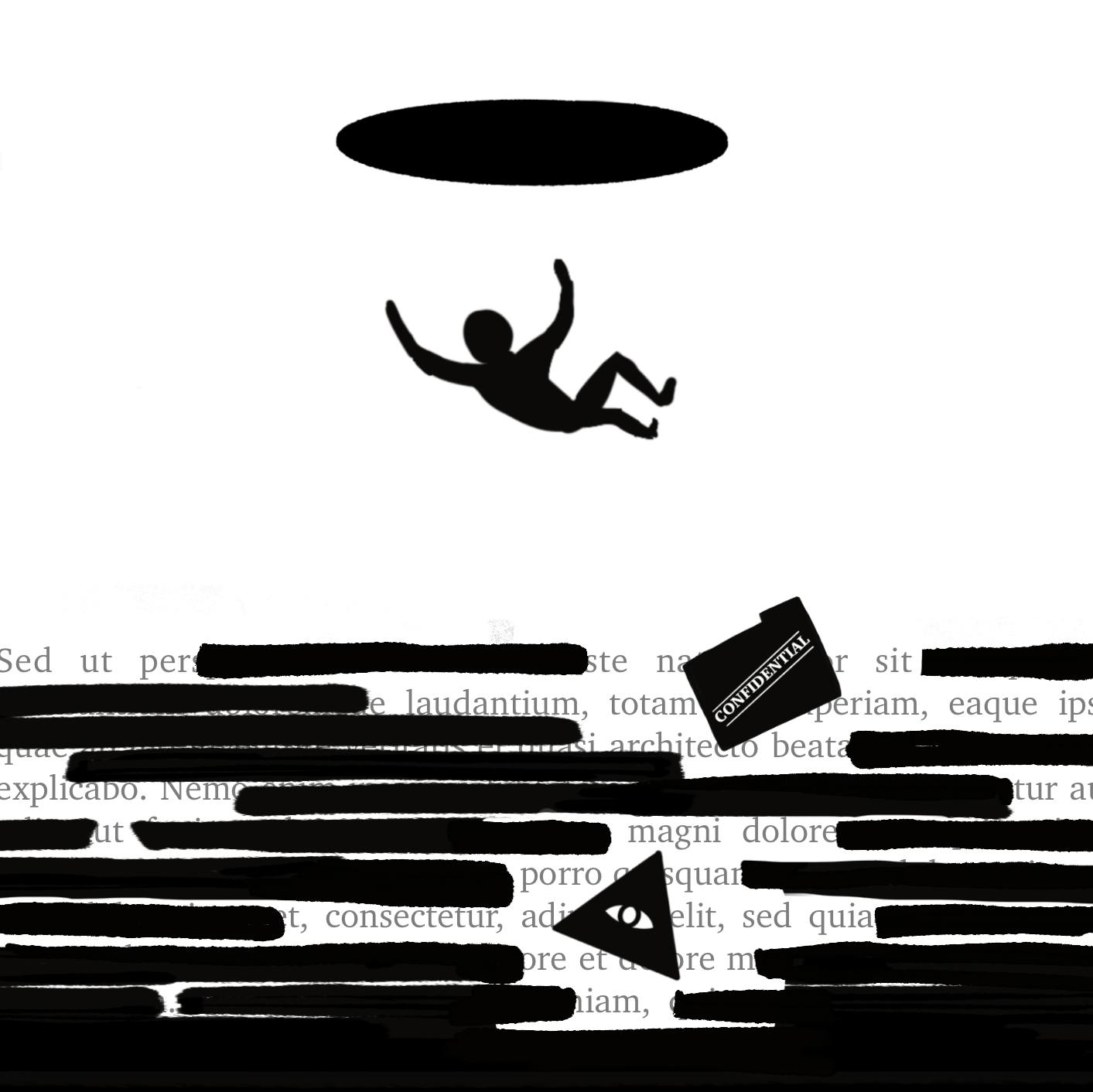

Fake news is everywhere, but what is it? What does it mean? The answer requires more than just a yes or a no. Truthfully, misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories have been built into social belief patterns that are nearly impossible to dismantle.

The history behind conspiracy theories

“The simplest thing to say — from a historian’s standpoint — is that conspiracy theories are always present,” Associate Professor Thomas Summerhill said.

Summerhill, who specializes in 19th century U.S. history in MSU’s Department of History, said that throughout U.S. history people have molded conspiracy theories from some type of truth.

Summerhill said an example of a misconstrued truth in U.S. history was rumored slave insurrections. Through the grapevine, masters would hear bits and pieces about how their slaves were dissatisfied with the treatment they were receiving. Masters then amplified this information, believing that a slave riot would soon become plausible.

But even then, Summerhill said this example is hard to prove. If slaves did admit to conspiring an upheaval, what was to say they didn’t just confess because their masters tortured them? He said humans will always be skeptical of the information we receive.

“It’s part of human nature to be secretive about things we don’t want others to know,” Summerhill said. “And so really, conspiracy theories really breed on a petri dish of our humanity.”

With secrets comes uncertainty. And with uncertainty comes anxiety.

Anxiety helps fuel the flame to turn conspiracy theories into political movements. Summerhill said an example of this was during the 1820’s and 1830’s, when middle class workers were stifled by the single-party system of Jacksonian democracy and rose up against the Democratic-Republicans with the creation of the Whig party. When political parties aren’t working for people, they tend to look to other theories for explanations. Summerhill said he sees that today.

“I think the United States is in a period of high anxiety and rapid change, and I think it’s having a hard time really sifting through and sorting out what’s real and what’s not,” Summerhill said. “As a historian, I link moments like this less to social media and more to whether or not the political parties are meeting the needs of their coalition constituents.”

Misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories. What’s the difference?

Intentionality.

Krishnan Anantharaman, a contributing editor to Poynter Institute’s fact-checking offshoot PolitiFact, said people can deliberately share information — whether it’s true or false — to get others to join their belief system.

“I guess I’ll call it malevolence, willful deception,” Anantharaman said. “Some people take information and say, ‘Wait a minute. I can fool people with this.’ And they put these two things together and just throw the grenade.”

This “willful deception” is considered disinformation and sets it apart from misinformation. While disinformation is shared consciously, misinformation often isn’t. For example, someone who shares a false post on Facebook — but doesn’t know it’s false — is engaging in misinformation.

Conspiracy theories are where the line gets blurred, Daniel Funke, a fact-checker at PolitiFact, said.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

“I think with conspiracy theories the difference is a little more nuanced,” Funke said. “It requires more of a larger level of buy-in than just like a normal hoax.”

He said while misinformation and disinformation can help shape conspiracy theories, conspiracy theories aren’t necessarily a direct result of either.

“It takes a lot more mental capacity for you to buy into something like QAnon,” Anantharaman said.

QAnon, an internet scheme anonymously birthed in 2017 to describe how President Donald Trump is fighting against a faction of Satan-worshipping pedophiles wanting to take over the country, has now become the soil for many new conspiracy theories to grow in.

The emergence of QAnon and other current conspiracy theories

Conspiracy theories flourish during a time of unrest, and — with a global pandemic, civil rights protests and an upcoming election — we are currently living in a time of unrest. When the answers to problems seem to conflict with what everybody says and believes, people tend to ease back into convictions aligning along the ideological dispositions they were initially comfortable with.

“People generally do not want to be shaken out of their existing beliefs,” Anantharaman said. “I think it’s very common when there’s cataclysmic events or events people have trouble understanding, they’re almost least likely to accept the simple explanation. This has happened with the JFK assassination, it’s happened with 9/11, it’s happening here with coronavirus, it’s happened with Black Lives Matter. Any one of these very convulsive, very disorienting or cataclysmic events in history … the conspiracy theories seem to fill that void of understanding that people are looking for.”

In May, during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, a documentary entitled "Plandemic" was released on YouTube. Mikki Willis, the director of the video, used former American research scientist Dr. Judy Mikovits to ignite feelings against a possible vaccine for the virus, contributing to the Big Pharma conspiracy theory that all pharmaceutical companies are evil. The video also conspires about the origin of the virus — one hypothesis is that Bill Gates started the pandemic to make himself richer.

"People with degrees are still capable of spreading misinformation," Funke said. "I think that showed fact-checkers have to work even harder to debunk this stuff. They had to explain to people that just because this person is a doctor or just because this video looks good doesn't mean it's credible."

But COVID-19 hasn't been the only topic conspirators have recently fed upon.

Kevin Roose, a tech columnist for The New York Times, tweeted on Sept. 14 how “Q,” the anonymous conspirator behind QAnon who claims to be an inside government official, released information about people who were recently arrested for fire-related crimes in California, Washington and Oregon. Also in the tweet, Roose said Q stirred up sentiment against Antifa, a radical left-winged, anti-facist political organization.

The raging wildfires out West during September have largely been attributed to climate change. But some believe that Antifa members were responsible for setting most of the fires.

Another theory taken over by QAnon is the #SaveTheChildren movement, a legitimate independent campaign that focuses on the welfare of children. Child trafficking is a real-world problem, but QAnon users have tied the hashtag to its own roots by saying there is an elite group of pedophilic political officials and entertainers running major child-trafficking rings in the U.S.

“QAnon appeals to a lot of base instincts in people,” Funke said. Some of these instincts, he said, include the American ideals to protect children at all costs and to distrust the government.

And while being skeptical is part of human nature, Funke said humans shouldn’t dive all in and believe these undependable remarks.

“Have a healthy dose of skepticism, but don’t be nihilistic and doubt official narratives,” Funke said.

How should we approach getting our information?

Assistant Professor Dustin Carnahan said he too believes healthy skepticism is a way to combat rogue information.

“I think especially when it comes to the source of information it’s always important to be skeptical,” Carnahan said. “I think there’s also the flip side, right? Being skeptical of everything is a problem because then we don’t have the resources — the cognitive resources — to think critically and skeptically about everything we read and see.”

Carnahan also said to gauge your emotions while consuming news because humans do have confirmation bias.

“We are all, I think, prone to fall prey to our passions,” Carnahan said. “We care about something so much that we’re willing to maybe drop aside reason and rational thought just so that we can feel good.”

Serena Daniels, a Detroit-based freelance journalist and local news fellow for the nonprofit news organization First Draft, echoed Carnahan’s advice to be wary of how you react to your news.

“Pay attention to your reaction to something that you might have seen,” Daniels said. “If it causes you to have a really profound reaction, then think twice about what that means.”

Daniels also said untrue, and even biased, information frequently uses strong trigger words to get an emotional response out of readers. Fact-checking sources is a way to combat these heightened emotions.

“When we see information going through our feeds that’s provocative, that provokes some sort of like gut reaction — whether it’s anger or fear or otherwise being upset – and you haven’t seen that information reported in what you would consider legitimate news organizations, that’s definitely a red flag,” Daniels said.

This article is part of our Information Overload print edition. View the entire issue here.