"The thing you didn’t realize while you were sexually assaulting me and all of these young girls and breaking our lives is that you were also building an army of survivors who would expose you for who you truly are: a sexual predator." - Amanda Thomashow, Jan. 17, 2018

Amassing an Army: Survivors create lasting change after Nassar

Approximately 300 pinwheels sit outside the Hannah Administration Building to represent all the survivors of Larry Nassar on June 22, 2018.

It’s been a year since more than a hundred women and girls — many of them athletes — stepped forward to tell their stories to courthouses full of reporters, attorneys, family members and fellow survivors.

In victim impact statements, they told of their encounters with Larry Nassar, the serial pedophile formerly employed by Michigan State and USA Gymnastics.

The survivors’ story didn’t end when a handcuffed Nassar was led out of a courtroom.

Months after Nassar’s sentencing, a young woman and about 40 others began the process of establishing an organization to assist other survivors, including those from athletic backgrounds, in healing and recovering from sexual violence.

In summer 2018, their efforts led to the foundation of The Army of Survivors, an organization created to “bring awareness to the systematic problem of sexual abuse of athletes.”

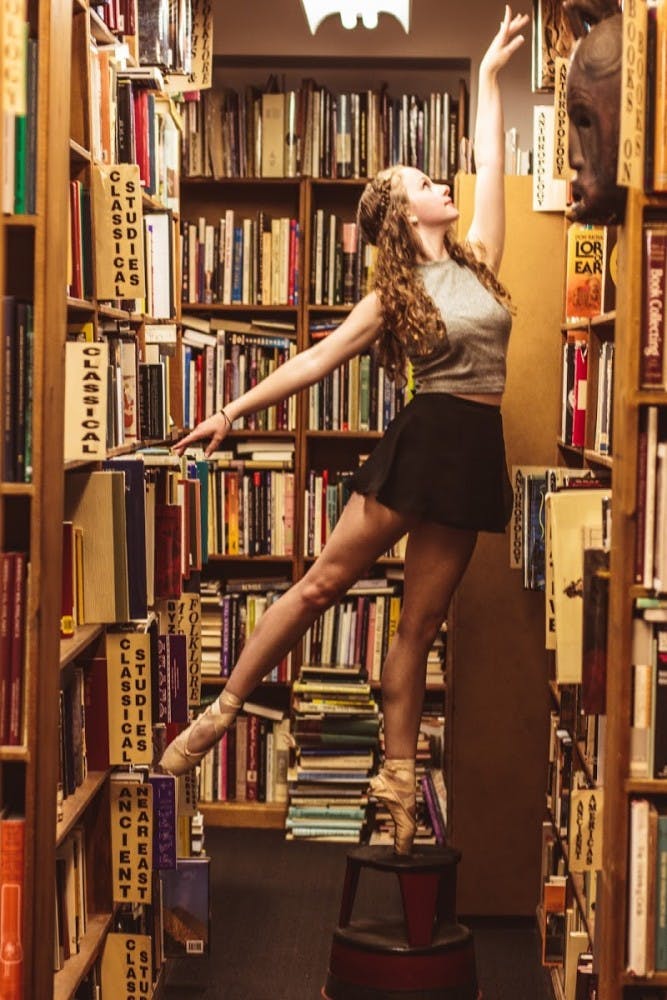

A classical ballerina

At a young age, Grace French knew she loved dancing. She loves plenty of different things: Coffee shops, traveling abroad and her current job with Shinola, a Detroit-based luxury goods company.

It’s in a coffee shop in her hometown of Okemos where French vividly recalls dancing. She describes taking intensive ballet classes from age 4 and keeping with the sport through college. Her career goal was to become a professional ballet dancer.

Dancing would later take a toll on her, but it was not a dance-related injury that first brought her to Larry Nassar. At 12 years old, French saw Nassar for her wrist, which she’d sprained on the playground.

She remembers that appointment and Nassar’s actions. She described his treatment as an “invasive massage.”

French continued to see Nassar for dance-related injuries well into 2014. Like hundreds of others, she was sexually abused by him. It wasn’t confined to his doctor’s office. Nassar’s treatments continued in the moments before she’d go onstage to perform with her company.

READ MORE

In an essay published September 2018, French wrote that at first, she didn’t see Nassar as her abuser.

“After all, my mom had been in the room at every appointment, he was an Olympic doctor, he treated all of the great gymnasts, figure skaters and dancers … I wanted to be just like them,” she wrote. “Even if I had told people I was uncomfortable with some of the treatments, would they have understood why they bothered me?”

The extent of his abuse came to light after dozens of news articles were later published. One after the other, more survivors came forward.

“Connecting the dots in my own story was devastating,” French wrote. “I felt my whole world and reality crash around me. The weight of his abuse and his control over the way I, my family and my community viewed him was too heavy even to comprehend.”

She experienced hip injuries too strenuous to heal — so significant that when she attended the University of Michigan, she dropped dance and switched to a business major.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Gathering The Army of Survivors

Years later, French was present in the courtroom alongside other women Nassar abused. His sentencing was imminent, but 30th Circuit Court Judge Rosemarie Aquilina allowed survivors to address Nassar first. French didn’t give a victim impact statement, but she recalls the one Rachael Denhollander gave.

“In the moment, when I was watching Rachael, I just had utter adoration for her,” French said. “It was nice to understand that some day in my healing, I would get to that point.”

Inspired by her fellow survivors, French began creating an organization that could provide resources, advocacy efforts and education to victims of sexual violence. Her goal was to ensure no person, athlete or not, would experience what she’d gone through.

While her plan for an athlete survivor organization was still young, French received a resume and cover letter from a Lansing woman. Louise Harder heard of French’s efforts. Like French, Harder was abused by Nassar.

As a teenager, Harder was deeply involved in athletics: Basketball, volleyball, water polo and diving. In 2009, her senior year of high school, Harder began seeing Nassar weekly for back pain.

She was recruited to join Albion College’s diving team, but stayed for only one semester. Continued treatment by Nassar began affecting her mental health.

She transferred to Oakland University, where she spent the rest of her college career. Harder obtained a degree in wellness, health promotion and injury prevention — essentially public health, she said.

That background was key to her joining The Army of Survivors. She now sits on its Board of Directors. As the organization’s main strategist, her experience in evidence-based programming is crucial to how the organization moved forward over the past several months.

“I was looking at other trends that were happening in the country right now or in the last few years that have had impacts on the survivors,” Harder said.

Trends she catalogued included the #MeToo social media movement, which swept the nation in late 2017.

“We’re trying to make sure that all survivors have a voice and share that through our web platform and social media,” Harder said.

Fine-tuning their mission

In December 2018, The Army of Survivors underwent a structural change.

With Harder’s analyses, she and the organization’s Board of Directors found there was no singular national U.S. organization with a specific mission statement dedicated to supporting child athlete survivors of sexual violence. The board voted to tailor their mission to fill that void.

“We are looking to expand nationally,” Harder said. “We have army members outside Michigan that are helping, but we’re trying to be more national and be that voice for athlete survivors.”

While their new mission is “to bring awareness, accountability and transparency regarding the sexual violence of athletes at all levels,” the goal is for their work to impact all survivors of sexual violence.

“It doesn’t matter where you’re from,” Harder said.

The Army of Survivors was already rooted in three principles, according to French: Providing resources to survivors of sexual violence, advocating for stronger policies to combat sexual violence and pushing for stronger education on prevention of sexual violence.

“We refer people to other organizations that have resources we found helpful,” French said. “That could be hotlines, that could be specific statistics that we found are really impactful, and having conversations around these things.”

On a national level

The Army of Survivors’ outreach is not limited to the Lansing area.

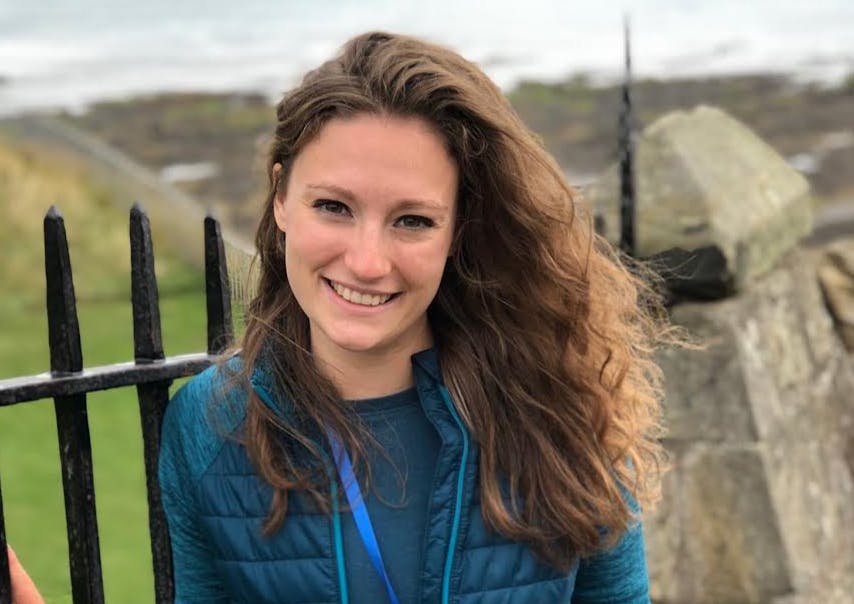

Outside of Michigan, 19-year-old health sciences freshman Megan Ginter attends Ohio State University. She and French are good friends — French is president and Ginter is the social media and public relations chair of The Army of Survivors.

Ginter met Larry Nassar at a young age, like French. Ginter experienced hip pain after years of practicing gymnastics and came to Lansing.

There at 13, she was abused by Nassar.

Years later, she’d travel to Lansing again — this time, to give her victim impact statement.

She was fearful in the courtroom. She said she felt even more vulnerable than she did the day she was abused.

“I was fearful going out in public, knowing that I’d have to be around a man,” Ginter said. “Whether I was with somebody or not, it was like life halted.”

In the year since then, Ginter said her life changed. Opening up publicly, talking to friends, managing social media for The Army of Survivors and getting involved in campus organizations has helped her heal.

“I never thought I’d be able to talk about it so openly like I do,” Ginter said.

Two years of therapy made her realize she couldn’t expect things to improve unless she put forth the effort to change things.

“I knew I did not want to remain the same,” Ginter said. “That wasn’t possible before I took the initiative and actually moved forward.”

Now, Ginter is part of the effort to establish The Army of Survivors as a nationwide organization.

“It’s been kind of difficult doing it as a student just because it’s so much going on,” Ginter said. “But I feel like this organization is so important because, at least to my knowledge, there aren’t any sexual assault prevention organizations for just sports, so this is needed.”

Building an army

Amanda Smith’s young children can be heard in the background when she answers the phone.

The 27-year-old Lansing resident and mother of two says she has spent her afternoon preparing to go to one of The Army of Survivors’ outreach events.

In attendance will be other sister survivors, members of the public and Judge Rosemarie Aquilina. The event is a speaker series hosted by The Army of Survivors and co-sponsored by the Michigan State University Museum.

Smith’s life now starkly contrasts the one she lived in January 2018.

Smith was in court for multiple days of victim impact statements. She initially decided that when her turn came, she would not go public.

Then before she spoke, she watched two 15-year-old survivors address the court, one being Emma Ann Miller. Her words made Smith decide to go public with her name in court.

“Looking around at all these women who went through the same thing as me, it made me realize that I had a voice and it mattered. I had a name,” Smith said. “I wasn’t a Jane Doe and a number, I was a person.”

Amanda Smith gives her statement on the fifth day of Ex-MSU and USA Gymnastics Dr. Larry Nassar's sentencing on Jan. 22, 2018 at the Ingham County Circuit Court in Lansing. "You were in fact the monster that they said you were," Smith said.

With her husband at her side, she was publicly named. In her statement, she told of her days as a gymnast with Twistars Gymnastics Club: At 8, she saw Nassar. The abuse happened when she was 13.

The Army of Survivors wasn’t even a thought yet, but the women collectively sharing their victim impact statements laid the groundwork for the organization.

“That really started the base of it, because we all became sisters at that point,” Smith said.

On MSU’s campus, the speaker series allows other survivors — not just of Nassar — to talk about their paths to recovery.

The series of talks that began in mid-January — titled “Finding our Voice: Sister Survivors Speak” — was organized by the MSU Museum and The Army of Survivors. The series leads up to the opening of the museum’s exhibit “Finding our Voice: Sister Survivors Speak” in April.

The exhibit is made up of 221 teal ribbons from MSU’s campus after the victim impact statements. They were woven around dozens of trees and tied near the Hannah Administration Building. MSU Museum Director Mark Auslander recalled the atmosphere on campus changing when the ribbons came to campus.

“It felt like there was this deep, dark gloom over campus and this was just a beautiful thing that was happening,” Auslander said.

Amanda Smith sets up a table of teal shirts, stickers and pages of resources for sexual assault and abuse survivors at the MSU Museum on Jan. 15, 2019.

The goal is to put that concept — and The Army of Survivors’ name — in people’s minds.

“When you’re believed from the start, it’s a lot easier to move on through the process,” Smith said.

That’s something that struck Smith as she gave her victim impact statement. In doing so, she began her own path to recovery.

“The biggest push in the right direction for me was being able to use all the animosity I had, and all the stress and turmoil, and turn it around and really help somebody else,” Smith said.

Moving forward

French says there are days where it’s difficult for survivors to continue building an army.

“There are some days where somebody who’s working with us will say, ‘I need to take a couple days off, it’s too much for me right now,’” French said.

Talking about sexual abuse and sexual assault every day is difficult because it can be triggering for survivors, she said. While the organization is comprised mainly of survivors, French said she wouldn’t change that for anything.

“I wouldn’t have it any other way. We all have this empathy and understanding of what survivors need and want,” French said.

Grace French calls for Interim President Engler’s resignation at the Action Meeting of Board of Trustees at the Hannah Administration Building on June 22, 2018.

Those within The Army of Survivors have dealt with tragedies with a goal in mind: Ensure no one else endures the same trauma.

“There’s been such a change in me individually, as well as us as a group, from taking something tragic and turning it into something great,” French said. “Pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps and saying ‘We can endure this pain every day so someone else doesn’t have to.’”

Larry Nassar was sentenced to 60 years in federal court, 40 to 175 years in Ingham County and 40 to 125 years in Eaton County. He spends his days at USP Coleman II, a high-security penitentiary in central Florida.

Meanwhile, The Army of Survivors aims to achieve nonprofit status by summer 2019.