In only her third soccer match in a Spartan uniform, White suffered her torn ACL, something female athletes face more than men.

In a 2012 game against Cal State Fullerton, the Coto De Caza, Calif., native was running when her knee “slipped” and she heard a “pop” noise. Just like that, her ACL was torn and her freshman year on the field came to an end.

“It was such a bummer,” White said. “It’s honestly so hard to watch your team play for so long and not to be on the sidelines not being able to be a part of it, especially your freshman year when you’re new to everything, that’s the year you want to prove yourself.”

White would spend every day for the next six months rehabilitating to make it back for the 2013 season.

For White, it looked as if her injury was behind her this season. The redshirt freshman was a key contributing factor to the Spartan offense for the first 11 games, scoring three goals and an assist. However, in MSU’s third Big Ten game against Wisconsin, White tore the cartilage in her knee. It left her sidelined for the last month of the season. She said two months would be the maximum for her current injury.

According to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, there are nearly 200,000 ACL tears in the United States every year, most of which occur in athletics.

Although both male and female athletes will experience ACL tears and other knee injuries, studies have shown women are more at risk of suffering an ACL injury, especially in the past 20 years as popularity in women’s athletics has risen.

According to the University of California, San Francisco, women are two to eight times more likely to sustain an ACL injury than men.

The magic bullet

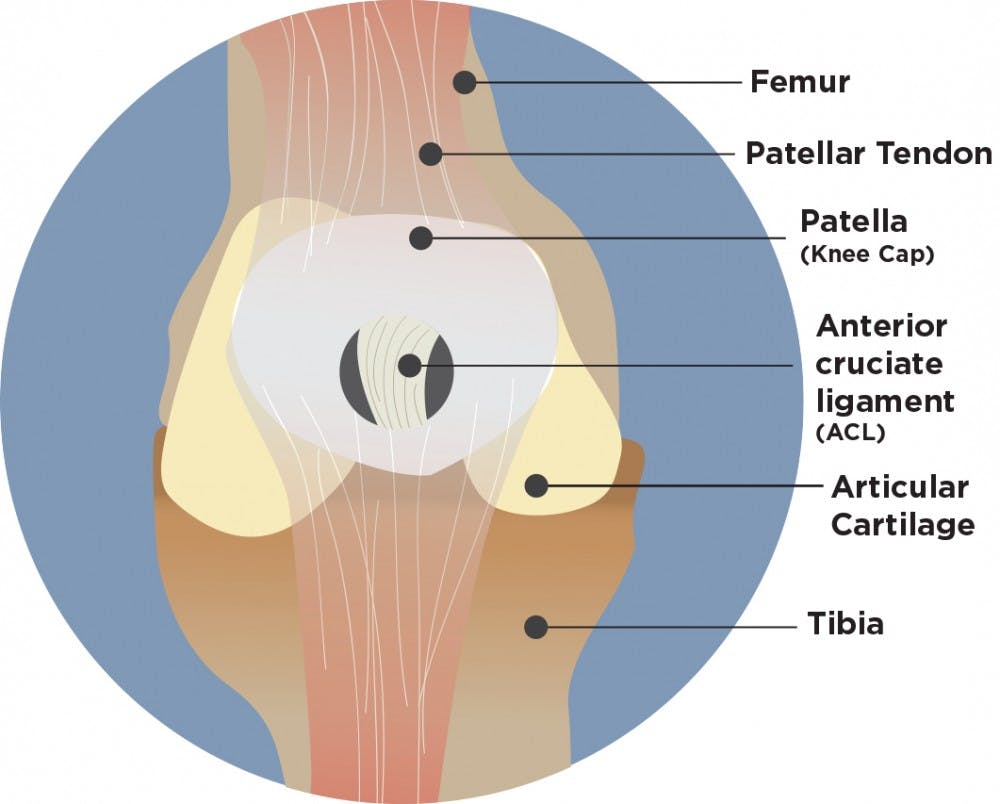

The ACL is the most important knee ligament and is one of four major ligaments in the knee. It is a band-like structure connecting the femur, or thigh bone, to the tibia, or shin bone. The other three ligaments are the posterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament and the lateral collateral ligament.

Dr. Jeffrey Kovan, MSU’s director of sports medicine and performance, said soccer and basketball are the most common sports that ACL injuries occur in because of a knee-driven culture that involves a lot of cutting.

Kovan said there are many factors that put women at a higher risk, but doctors and medical experts still are searching for exactly what causes the injury.

One of the uncontrollable factors is the width of women’s hips, or the “Q” angle — the width from the hip to the knee.

Since women typically have a wider pelvis than men, which creates a longer “Q” angle than men, Tim Wakeham, the director of strength and conditioning for olympic sports, said the longer “Q” angle can create instability in the knee.

Wakeham also said a factor to consider is hereditary. He said if a mother had a non-contact ACL injury, her daughter will be at a higher risk of sustaining a non-contact ACL injury.

Kovan also said experts have looked at whether women’s knee injuries occur more around the time of a woman’s menstrual cycle when the laxity, or looseness, of some of the joints are greater.

“Everybody is trying to find the magic bullet, what is the marker that tells us who is at risk,” Kovan said. “There’s a lot of different factors and everybody teased out all those different ones and nobody’s come up with ‘Here is a couple things we know that put you at risk,’ and that’s what we’re still trying to figure out.”

One of the controllable factors that could help decrease the injury rate is muscle strength, Wakeham said.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

He said women tend to be much weaker in their hamstrings than their male counterparts, and hamstrings are a muscle that tries to prevent instability within the knee as the leg moves.

The athletic training and strength and conditioning staffs also lead the players through balance exercises, as well as teaching recovery techniques from bad movements the player might encounter during their sport.

Kovan said, theoretically, tearing one doesn’t put you at risk of retearing the same ACL. For players like White and MSU women’s basketball player Branndais Agee, they will have a 25 percent higher risk for retearing their ACL and increasing the odds of tearing the other leg’s ACL, Wakeham said.

Agee, a redshirt freshman guard for MSU women’s basketball, tore her ACL in an early-December practice last year. She only played in five games across the season after the injury.

Decreasing, not preventing

Like White’s injury, about 70 percent of all ACL injuries in women are non-contact. They can stem from a jump the wrong way, or trying to stop suddenly.

Wakeham said many experts used to say they would use an ACL injury prevention program, but because of the severity and commonality of the injury, experts now just try to decrease the rate of injuries.

For Wakeham, who has worked with the women’s basketball team the previous two seasons, dealing with ACL injuries is the most difficult part of his job, but he won’t accept just being able to decrease the injury — he wants prevention.

After an ACL injury to a player last season, Wakeham visited nationally recognized physical therapist Gary Gray to see if there were any new things Wakeham could add to his own program at MSU.

Although his job is to enhance performance, most strength and conditioning coaches have started to do all they can do to help sports medical staff members prevent these injuries.

“It’s kind of an all hands on deck (issue) — this is probably the No. 1 issue in women’s athletics, right now,” Wakeham said.

Coming back

After a player has surgery to repair an ACL tear, Kovan said it takes about four to six months, or even longer, to return to functional activity, such as running or cutting.

For the first four to six weeks, the player spends time in a brace and only works on range of motion.

Kovan said most athletes are back playing within nine months, but it usually takes a year and a half to two years before an athlete is back to his or her former self. It is rare to see an athlete, like the NFL’s Adrian Peterson, come back in a short time span.

“The Adrian Peterson’s of the world are a little different, but that’s a rare one,” Kovan said. “That’s just a little luck on his end and those things, but usually back to playing in nine months.”

Although a player can be fully healthy, after having such a grueling rehab process, it can take a toll mentally.

Kovan said it affects each player differently. It can take time to have the confidence to play again.

For Agee, regaining confidence was the hardest part.

“Just not being afraid to play on it, and defense … was very scary for me because that’s how I got the injury,” Agee said. “I was kind of scared to play defense, but now I should be good.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “The long road back” on social media.