It’s a steady upward trend: climbing, climbing. That gradual, but merciless climbing. It was $179.75 in 2002, $197.50 in 2003, and $206.25 in 2004. Shave a little here. Add a little there. Jump ahead five years to 2009, and it’s already $347 per credit hour in the fall semester. Then $371.75, $406.75 and finally $420.75 in the fall of 2012.

Tuition is rising. It has been for a long time.

But next year’s $49.5 billion state budget, signed into law on Thursday by Gov. Rick Snyder, includes a 2 percent funding increase for higher education.

It’s a $31.9 million boost for universities and colleges, and the governor, Republicans, college administrators and higher education lobbyists hail it as a victory.

“We should be proud of the financial stability that is now firmly established within the state budget,” Snyder said at the bill-signing press conference last Thursday. “This is a great education budget. It’s about investing in our students — our future.”

Republican Speaker of the House Jase Bolger said this year’s appropriation is a reversal of the decadelong trend.

“We pressed the reset button when we came into office a couple years ago so that we could realign and grow,” Bolger said in an email. “We did that because we believed that when the pocketbooks of Michigan’s families got healthier, the state budget would get healthier. That’s exactly what we’re seeing now.”

Yet a bitter taste lingers in advocates’ mouths.

Mark Burnham, MSU’s vice president for governmental affairs, said the increase “is important, but it isn’t a big amount of money.”

He said it’s impossible to know how much it will affect tuition until MSU’s Board of Trustees meets this Friday, where it determines the price every year.

Growing debt

Raul Orduna is a social work senior who’s troubled by what he calls “backward” priorities.

Orduna managed to make it to his senior year with only about $12,000 in debt, keeping afloat with scholarships and his 25-hour-a-week, $11-an-hour job at Brody Square. He said he’s not too worried about his modest debt right now.

“It’s manageable,” Orduna said. “My real concern is grad school.”

Orduna said he wants to get his master’s degree in social work, but still hasn’t worked out how to get the money to do so.

“Probably just loans,” he said.

And many people have done the same. The average student debt is about $26,000 a year, according to a report from the Institute for College Access and Success. Some rack up an even bigger tab.

“It’s absurd,” Orduna said. “The one buddy I worked with at the cafeteria said he owed $56,000.”

Total national student debt has risen to roughly $1 trillion, higher than auto, credit and home equity loans.

It’s all politics

Michigan saw one of the biggest funding drops for colleges and universities in the nation, according to a recent 2013 report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers, a nonprofit organization that researches higher education policy.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

This year’s modest increase doesn’t begin to make up for deep funding gouges since Snyder took over, critics say — a 15 percent reduction during his administration alone, continuing a long downward slope of state aid, passed from one governor to the next like some debt-inducing Olympic torch relay.

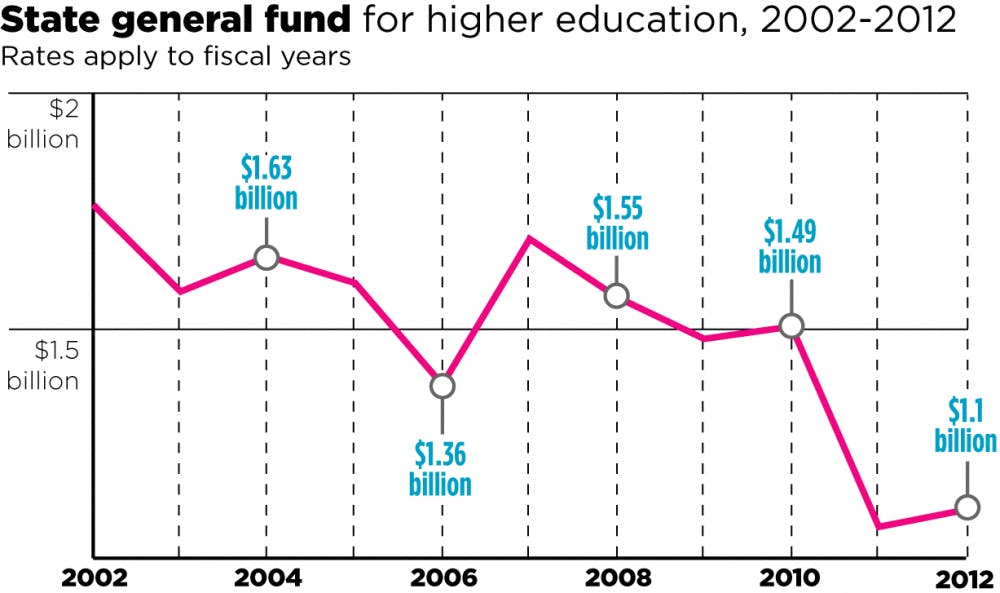

In the same years as above, the state appropriated $1.8 billion in 2001-02 for higher education — then $1.7 billion in 2002-03, and $1.6 the next year. Skip ahead to 2012-13 and it’s down to $1.1 billion.

Advocates such as Burnham say it would take an increase of $100 million every year for 10 years before state funding was brought back to pre-10-year-slash levels.

“It’s not economics, it’s a political reality,” said economics professor Paul Menchik. “Look around the country … it’s a widespread trend, and it’s more political power than a cost benefit analysis of what’s in the interest of the state.”

Menchik said research shows economic growth correlates with generous higher education funding.

So why is funding so low? One reason is insufficient state revenue, Menchik said, which would be much higher with a graduated income tax, he continued. So why is Michigan one of the few states with a flat-rate income tax?

“Look at how we fund elections with campaign donations,” he said. “Not everybody speaks with the same voice in terms of the, oh, political effects. The $200,000 guy has more influence than the $20,000 guy.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “Snyder inks budget with higher ed funding boost” on social media.