At the same time, a group of students are pioneering a new house, Howland, that was lost for the last several student generations, attempting to form a new culture while reviving a gem of co-op heritage, a balance they said is tough to achieve and only will come into full bloom next fall when the new members settle in.

The reformation of two houses — one being resurrected from the early days of co-op history, the other a strict reform of a house in conflict with MSU Student Housing Cooperative, or SHC, leadership — is giving the community a rare chance to assess itself from the inside out. Both instances are allowing members to articulate the values of this unique type of housing arrangement that centers on collective participation and, above all, a spirit of cooperation.

The Avalon factor

Kevin Carlson remembers what it was like last year, when partying and drug use pervaded what was then called Avalon, a large co-op house sandwiched in a row of fraternities on Harrison Road.

There often were parties with loud disc jockeys and people filling the house’s basement, obviously on drugs, Carlson said. More often than alcohol, it was “hippie drugs,” he said — LSD, mushrooms and molly, a powdered form of ecstasy.

“Walking around our parties, seeing everybody bugged out, it got kind of weird sometimes,” said Carlson, an environmental geosciences senior who is spending his second year in the house, which was renamed Walrus Farm cooperative house this year by a house vote. “You expect that at any party scene pretty much, but I feel like some of the parties were just stupid.”

During the course of Ben Rausch’s time there from summer 2010 through summer 2011, the house fell into disarray, the civil engineering senior said. Funds ran out, there was no more food. People stopped doing chores or attending meetings. That, he said, was a more destructive issue than drugs, which he feels is more rumor than fact.

“It was a good time living there, but it was totally irresponsible,” Rausch said.

Those who live in co-ops paint a mixed portrait of what went on in Avalon — but both those who live in the house and others said it has carried a negative stereotype from previous years, and members this year are attempting to bring the cooperative spirit back.

Although some information was redacted in police records from the East Lansing Police Department, they do not show any responses for drugs, only a handful of thefts between 2008 and 2010.

“(The reputation has) just been building up, and I think kind of symbolically,” said English senior Andrea Goossens, who lives in Phoenix cooperative house. “They’re fighting that stereotype.”

Currently, members are working to refurbish parts of the house. Painting materials cover the downstairs living room area, and the members insist the culture of drugs and apathy is a thing of the past.

“I still think the reputation sticks with the house no matter who lives there,” said Maureen van de Water, vice president of membership for the SHC, noting there were problems with drugs at Avalon in previous years.

Van de Water said she started pushing for a recolonization after it became apparent the SHC would have a difficult time filling all the of the rooms in Avalon; currently there is no one signed up to live in the house next year.

“We have to do our best to make sure people were really excited to live (in Avalon), and we just weren’t seeing it,” SHC president Matt DeNinno said.

No two alike

It might be more understandable why the SHC is sensitive to such stereotypes, considering the organization’s volatile history of drugs and embezzlement.

Historical records documenting the organization’s history on file in the SHC office outline a sting of embezzlements and drug operations.

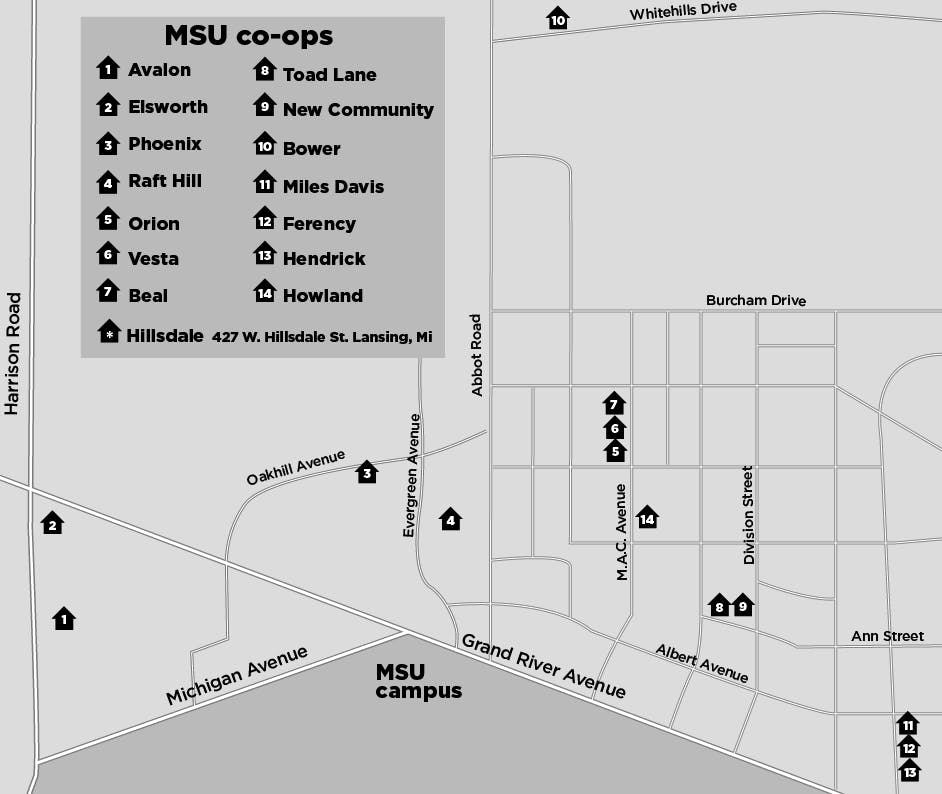

Cooperative houses had been forming independently near MSU since 1939. In 1969, the same year New Community cooperative house opened as its own entity seeking to live in a utopian-style environment, the SHC became a corporation with three houses. The ‘80s and ‘90s were particularly steeped in trouble. In 1985, the SHC president embezzled money from the corporate account to pay her tuition, according to records. Between 1989 and 1991, the SHC bookkeeper embezzled more than $75,000, using the money to buy cocaine that she and others used in the office.

During that period, the SHC president used the company account to purchase nitrous oxide, and then resold it at parties.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Visiting houses today illustrates a wide diversity in size and attitude, all sharing the same value of unity that make living in a co-op a far different experience from other types of living arrangements.

The SHC is a public corporation where members buy shares instead of paying rent, meaning the students who live in the house actually own it, at least while they are there. For members, that makes all the difference.

“Because it’s like this ownership, you feel this responsibility to improving the house,” social relations and policy junior Josie Bradley said, who lives in Toad Lane cooperative house. “It’s like an automatic community.”

Although members said many people see them as hippies or hipsters, the insides of each house show different cultures depending on size and type of resident.

“I hesitate to call it hipster, indie or anything like that, but you have to be a certain type of person to want to live in a co-op,” said Gina Rome, who graduated from MSU in 2011 and still lives in Phoenix. The SHC uses student status somewhat loosely, as recent graduates within the last few years still are allowed to live in the houses.

Nick Huff, an electrical engineering senior who lives in Owen Graduate Hall, didn’t use an “H” word to describe co-ops. Huff said he often comes just to have fun in a laid-back environment.

“It’s a fraternity without the cult atmosphere,” he said, holding the door open while people piled into Vesta cooperative house for a jazz-band party on a Friday night in February.

Houses can vary considerably. Phoenix is the largest with 29 spots, all but one of which are filled this year.

In a recent appraisal, the house — a white, old fraternity house perched on a steep hill overlooking Valley Court Park — was valued at more than $1 million.

Elegant, old staircases wind through the cavernous house, with elaborate, brightly colored murals painted by the members throughout the years.

“For the first probably week that I lived here, I got lost everyday,” said Rome. “It’s kind of like a labyrinth.”

Howland

While one house is in reformation, another is in resurrection.

A group, now nearing the 19 maximum capacity of the house on M.A.C. Avenue, is preparing to pioneer a new, victorian-style house named Howland cooperative house and is slated to open next fall.

Both those forming the house and living in it next year said they hope the house will be part of a solution to cure general apathy across the co-op community.

“I definitely see a lot of member apathy in established houses,” said Brendan La Croix, a professional writing senior who is living there next year.

Howland opened in 1948 and was shut down about a decade ago after running into severe drug problems and failing a city inspection, before being bought out by a management company, La Croix said.

Now, maintenance people are working there almost daily to prepare the house for its opening.

“That’s what co-ops are about, is shaping the culture,” said Julia Coron, a member of the committee reforming Howland. “How I see it is just sticking to the core of what co-ops are.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “A community of co-operation” on social media.