In the twilight of his career, however, he can’t help but wonder how his younger colleagues will navigate a higher education landscape irrevocably altered by generative AI. Arch expects younger faculty will expend copious amounts of energy throughout their careers to keep pace with the technology’s current and future iterations, he said.

Since OpenAI released ChatGPT in 2022, kicking off the mass adoption of generative AI, educators — particularly those in writing-centric disciplines — have found themselves in an arms race against AI developers and their students. More often than not, they feel like they’re struggling to stay afloat.

MSU lacks a university-wide policy on generative AI. The university has released guidance that outlines the technology’s potential uses and risks, but professors are free to decide to what extent AI can be used in their classes, if at all.

There’s also no consensus on whether or not AI belongs in the classroom. Computer science faculty have been quick to incorporate the technology into their curricula, citing its value as a learning tool. Not relegated to STEM either, an MSU professor teaching electronic art & intermedia is also leveraging AI in her classes.

Faculty who have decided against the use of AI, on the other hand, have turned to a smorgasbord of tools for sussing out AI usage in their classrooms, although their reliability is a source of disagreement among educators — as is the ability of professors to identify AI-generated text. The additional responsibility of policing AI usage, a task which few faculty members were prepared to undertake, has come at a significant price for professors’ time and energy, they said.

MSU has also moved to increase student, faculty and staff access to AI tools, leading to frustration among professors who feel the university has further stacked the cards against them.

"Encouraging the use of AI while also having no officially approved tools or policies for AI detection makes it extremely hard for me to teach students to think through writing," said Emily Katz, an associate professor of philosophy.

Unreliable, necessary tools

Tools meant to detect AI-generated writing have been some of the only countermeasures available to professors trying to keep the AI out of their classrooms. However, the reliability of those tools is a common source of conflict among faculty.

As generative AI began to take root in classrooms across the country, education-focused software companies moved to promote new suites of applications purportedly capable of detecting AI-generated text. The accuracy of those programs, however, was quickly called into question, with researchers observing high error rates across platforms.

One AI detector created by Turnitin — the software company known for its similarity detection service — was briefly available for MSU faculty before the 2023 fall semester. Citing concerns that AI detection tools can produce false positives and false negatives, the university disabled access to the detector for users with a university subscription to Turintin in August 2023, an MSU spokesperson said.

Faculty largely said they agreed with the university’s finding that results from AI detection tools couldn’t be taken at face value. Even so, many said they still use those tools — paying out of pocket to do so — as a surface-level defense against AI usage.

"If something comes back up to 15% AI-generated, I’m just not going to worry about it," Katz said. "But anything above that, I’m going to take a closer look."

The potential for false positives informed Katz’ 15% threshold, which she settled on after discovering essays written before the release of ChatGPT would occasionally be marked as one, two or five percent AI-generated.

Other faculty members, like James Madison College Associate Professor Susan Stein-Roggenbuck, said they’re distrustful of any software claiming the ability to identify AI-generated submissions.

"There are no good detection tools out there," Stein-Roggenbuck said.

Seemingly acknowledging some students’ anxieties over their work being incorrectly flagged as written by AI, Katz said she encourages students to use those same programs to vet their work — although she said she would never accuse a student of unsanctioned AI usage solely based on a detection tool’s output.

An eye for human text

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

Several professors claimed to be able to distinguish text written by a human from AI-generated writing, even without the assistance of AI detection tools — an assertion that has found mixed support from researchers and other faculty members.

In addition to AI-generated text being "extremely obvious," Katz said there are several key tells that help her identify machine-written submissions. Generative AI tends to use a lot of words to say very little, compared to students who have plenty of original, interesting ideas to share — even when their grasp on the class material is shaky. In short, "grammatically perfect and completely vapid" papers immediately raise suspicion.

In contrast, outside extreme instances of AI usage, Arch said, "it’s impossible" to discern human-written work from its AI counterparts. That task can become even more challenging with students developing sophisticated prompting techniques. Assignments that don’t require students to cite their experiences or quote class materials are also susceptible to AI usage, he said.

Arch cited an experiment he’s run with colleagues several times, presenting them with five writing samples — some written by students and others generated by AI. Overwhelmingly, Arch said, people aren’t able to distinguish between the two groups.

"I’ve had colleagues at other universities who claim to be able to tell the difference," he said. "I think they’re wrong."

The AI police

Even if a professor is certain that a student’s submission is AI-generated — and has the somewhat authoritative backing of an AI detection software — enforcing their AI usage policy presents a new set of challenges.

Arch said he’s never reported a student for using AI on an assignment, and doesn’t think he ever would. More likely, Arch said, he’d be interested in speaking to the student about how they use AI and determining what could be a more productive way to use the technology.

That non-punitive practice is also seen in the detection tools Arch uses in his IAH and English classes. He uses Packback and Perusall, softwares that don’t punish students for submitting AI-generated work but instead encourage them to rewrite the assignment.

For Katz, however, enforcing strict control over AI usage in her classes feels necessary to protect students trying to learn traditionally. No one putting in the effort, she said, wants to feel like a "sucker."

To that effect, Katz said she’s filed academic dishonesty reports against students caught using generative AI in the past. Even when she confronts students with an AI likelihood score from GPTZero and her intuition, students don’t always fess up. Often, it depends on how cornered a student feels and if they’re offered an opportunity to rewrite the assignment, Katz said.

The task of policing AI usage places professors, Katz and Stein-Roggenbuck both said, in an uncomfortably adversarial relationship with their students. It’s also an additional responsibility that comes with a significant toll on their time, energy and patience.

"I really don’t want to be the police," Katz said. "But if the university is not going to have clear guidelines for students and faculty, then I guess I have to do this on my own."

A laundry list of responsibilities

About 20% of the time Katz used to devote to grading and providing personalized feedback to students has been replaced with time "trying to figure out" if her students used AI, she said.

Even if they aren’t regularly inspecting submissions for potential AI usage or calling students into their office to confront them, professors are expending considerable resources retooling their curricula for the AI era.

There are essay prompts to be rewritten to demand greater specificity, projects redesigned with checkpoints to force students to show their in-progress work and discussion questions made answerable exclusively through video rather than text. It also takes the forms of another policy appended to the class syllabus and a plea at the beginning of the semester, trying to convince students that using AI isn’t in their best interest.

MSU’s guidance on AI in instructional settings provides some resources for faculty to more smoothly implement generative AI into their classes. But finding the time to digest those resources and familiarize yourself with the technology is a considerable time investment, Stein-Roggenbuck said.

Becoming proficient AI detectors and mastering its use in class, she said, feels like one more task being added to professors’ ever-growing list of responsibilities — a list that has drastically grown in the years since the COVID-19 pandemic.

"I want (MSU) to stop telling us to do more — more in terms of what we need to be able to navigate day to day," Stein-Roggenbuck said.

Where do we go from here?

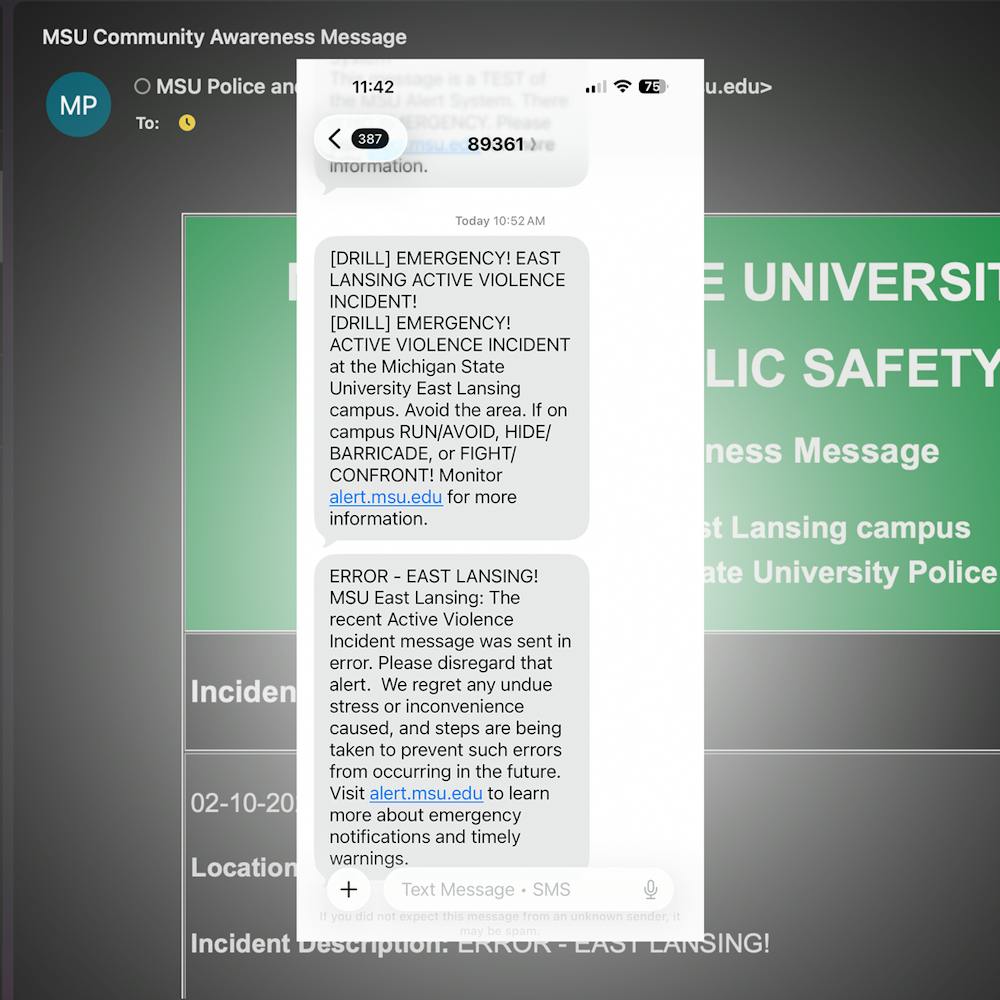

Earlier this month, MSU announced that it is in the process of implementing Google Gemini and ChatGPT access for faculty, students and staff. MSU users have had access to Copilot — Microsoft’s AI assistant that can generate text, summarize documents and generate images — since September 2024.

Generative AI, it seems, is here to stay.

Although some faculty members have valid reasons for not wanting to incorporate AI into their instruction — including its environmental impact and ability to replicate social biases — instructors in the arts and humanities will need to be thoughtful about how to curate student experiences in the AI era, said Garth Sabo, the director of the Center for Integrative Studies in the Arts and Humanities, or IAH.

Concessions are going to be necessary, Arch concurs. He has been assigning less reading as of late and scoring class discussions for participation rather than quality to get students to take intellectual risks. It’s a departure from the teaching style he used when first starting out in 1989, but part of the job has always been about adjusting, he said.

There are other moments, Arch said, like when he brings in a short essay, poem or artwork for students to chew on in class, where he succeeds in pulling students away from their increasingly technological world and into a grounded classroom. On some level, he said, students know that the technology around them can get to be too much sometimes.

"I think, in a strange way, some of them actually like the fact that we’re putting it down and now we're just doing old-school discussion," Arch said.

Discussion

Share and discuss “As AI takes root at MSU, humanities faculty struggle to keep pace” on social media.