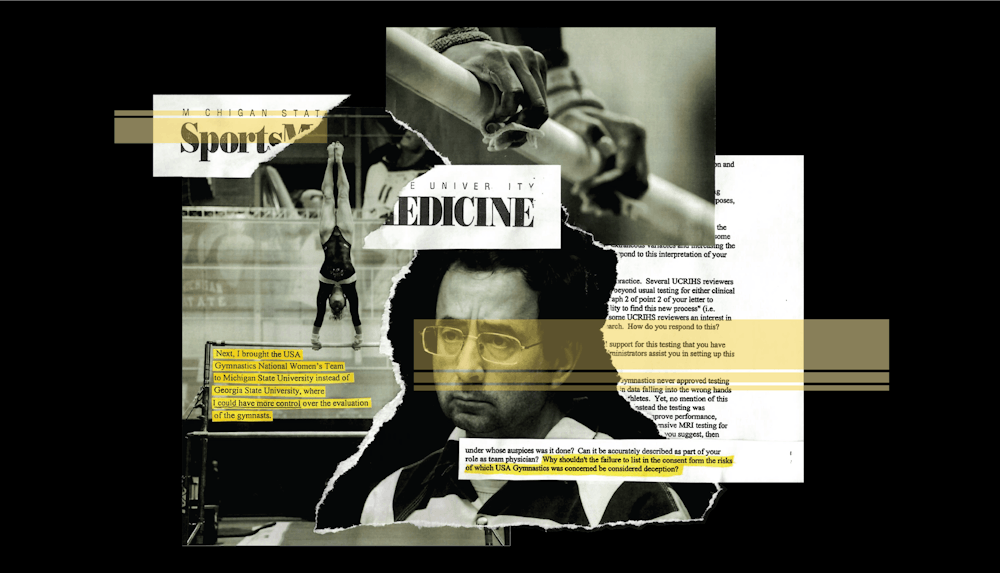

Long buried documents reveal a bizarre new tale about disgraced former doctor Larry Nassar, with Michigan State University disciplining him for research issues more than a decade before sexual abuse allegations became public.

In the late '90s, Nassar apparently convinced begrudging leadership at USA Gymnastics to allow him to conduct a series of blood tests of young gymnasts at his MSU lab.

When MSU’s committee overseeing human use research caught wind of Nassar’s project, it launched an investigation. Then, when Nassar didn’t respond to their questions, he was suspended from conducting any human use research on campus. And, for the three years after the debacle, MSU deemed it necessary for an appointed "mentor" to oversee all of Nassar’s research activities.

Members of the university research sub-committee tasked with investigating Nassar suspected his blood testing project went beyond the duties typical of a team physician, and that he may have deceived gymnasts and their families when seeking consent for the blood testing, records show.

The previously unreported tale greatly challenges a narrative surrounding Nassar’s years of unchecked sexual abuse.

Onlookers have long said that Nassar may have been shielded from scrutiny by his prowess as a sought-after doctor and his status as a sort of icon in the insular world of gymnastics. At his eventual sentencing, the prosecutor said that amid claims of sexual assault, Nassar’s post as a well-respected physician was a "perfected excuse."

The blood test saga complicates that story. Correspondence obtained by The State News through public records requests suggests that both institutions that long ignored claims of Nassar’s abuse — MSU and USAG — had doubts about the ethics and scientificity of his work.

"They had reason to know he played fast and loose with rules and informed consent, which ought to have given greater pause when sexual abuse allegations rose up," said Rachael Denhollander, the first woman to publicly accuse Nassar of abuse who is now an attorney advising institutions on issues of sexual misconduct.

Nassar’s idea

Gymnastics had a PR problem, Nassar argued in a 1999 letter explaining the blood testing to MSU investigators.

He wrote that the media was unfairly scrutinizing the health of young gymnasts, especially after one of the sport’s stars died of organ failure prompted by anorexia.

"Since they are looked upon as 'cute little girls', we are constantly under the media microscope," wrote Nassar, then USAG’s top doctor.

He took particular issue with a then-recent book, "Little Girls in Pretty Boxes," which described "horrors endured by girls at the hands of their coaches and sometimes their own families."

In the years since he criticized the book, it has ironically become quite intertwined with Nassar. It’s been republished with new chapters about his serial abuse and is advertised as a sort of prequel to, or explanation of, his exploits. Promotional materials say the book "shows how a longstanding culture of abuse made young gymnasts the perfect targets" for Nassar.

Nassar thought he could dispel the book’s findings. After its publication in 1994, USAG started doing nutritional testing on athletes with food diaries and surveys. But Nassar worried the results would be inaccurate, because the gymnasts could falsely report their food intake.

So, he then pitched a system of blood tests on USAG’s athletes.

Nassar claimed that USAG was skeptical of his plan, writing that they worried "the information would fall into the 'wrong hands' and … turn into a media event."

USAG declined to answer questions from The State News. A spokesperson said in an email that the organization "is unaware of the matters you have inquired about."

Eventually, though, Nassar claimed to have convinced the athletes, parents and relevant coaches of the importance of the tests, according to his letter. They ultimately signed consent forms Nassar wrote allowing for the testing.

USAG’s previous medical and nutritional screenings were conducted at Georgia State University. But, for the bloodwork, Nassar brought the gymnasts to his office at MSU, where he was an assistant professor.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

There, Nassar "could have more control over the evaluation of the gymnasts," he wrote in the 1999 letter.

The results of the tests were helpful for his clinical work as the team doctor, Nassar wrote. Later, he decided he wanted to do more with the data. He sought to conduct academic research on "some interesting trends" he saw in the bloodwork.

So, he asked MSU’s University Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (UCRIHS) for permission.

The committee responded by opening an investigation into Nassar, questioning the work altogether.

The committee's skepticism

After requesting approval from MSU for a "retrospective analysis" of the data he had obtained through the blood tests, Nassar received an extensive inquiry from UCRIHS.

"An Investigative sub-committee has been formed to review your research with the Olympic gymnastic team," the committee wrote to Nassar. "You are assured that UCRIHS is not investigating malpractice, that is not what we do; we are responsible for assuring protection for human subjects participating in research."

The committee asked Nassar to detail "the reasons blood was obtained on these patients" and clarify whether the testing was "considered research or clinical practice of medicine (or both)?" But what appeared to be the committee’s most pressing concern was how Nassar obtained "informed consent" of the patients and their families for the blood testing, and the ethical soundness of those methods.

Nassar appeared defensive to this line of questioning, claiming that the informed consent form he presented to gymnasts and their guardians in relation to the blood testing was approved by the chair of MSU’s committee "in advance of the blood work."

"Let me re-state this again. I showed David E. Wright the form in question and he approved the use of the form," Nassar wrote. "The intent of the lab work was for the evaluation of the gymnasts’ health."

There was also dispute over whether the form was for the consent of the patient and their guardians for medical treatment, or for research purposes: If the form only concerned consent for medical treatment, then it wouldn’t be permissible for Nassar to use the data he obtained through the tests for his "retrospective study."

But Nassar maintained that the form did, in fact, encompass consent for data obtained through testing to be used for research purposes.

Nassar quotes directly from the consent form, which was not included in the documents obtained by The State News: "I understand that the Faculty Group Practice is involved in education and research activities. These research activities may involve examination of my medical record in which my name and other identifiable information will be kept confidential."

Nassar then claims that the committee's chair told him prior to starting the blood work that if, in the future, Nassar decided he wanted to conduct a "retrospective review" of the data he obtained, he could do so by submitting a request for approval to the committee.

In a follow up to its initial inquiry of Nassar — aside from pressing for "documents that describe the purposes, methods and details" of Nassar’s blood testing of the gymnasts — the committee raised further questions about the consent form.

These questions, though, were prompted by Nassar’s admission that USAG itself didn’t initially approve of the blood testing.

"In your letter to UCRIHS you indicate that USA Gymnastics never approved testing for fear that to put it 'on the record' might result in data falling into the wrong hands and adversely affecting the sport and/or individual athletes," the committee wrote. "Yet, no mention of this risk was made in the informed consent you provided; instead the testing was presented in only a positive context...

"If USA Gymnastics never approved this testing as you suggest, then under whose auspices was it done? Can it be accurately described as part of your role as team physician? Why shouldn’t the failure to list in the consent form the risks of which USA Gymnastics was concerned be considered deception?"

The committee’s skepticism didn’t stop there.

Several committee members were "inclined to view" that the blood tests described by Nassar went "well beyond usual testing for either clinical practice or team monitoring." They also write that Nassar’s admission that he brought the gymnasts to the MSU campus for the testing "strongly suggests… a research interest."

"How do you respond to this interpretation of your description of the project?"

Nassar doesn’t respond

It appears Nassar didn’t respond to that question, or the follow up inquiry at all, for that matter.

After the committee apparently didn’t receive a response from Nassar to its follow up inquiry, William Strampel — Nassar’s former supervisor and the only person aside from Nassar to do jail time in connection to the Nassar scandal — entered the fray, along with other high ranking administrators.

In an email sent to Nassar weeks after the committee’s follow up, Strampel referenced a phone call he appeared to have with Nassar earlier that day. In that conversation, Nassar said he had not yet received "the request for information" from the committee "as of this time," but would respond to the request "immediately upon its receipt."

Strampel then told Nassar, “You are aware that the Vice President for Research has specific interest in the resolution of this issue” and that Nassar would not be permitted to conduct any “human use research on this campus until this matter is resolved.”

Strampel suggests to Nassar that he go to the committee’s campus office if he doesn’t receive the inquiry by 12 p.m. that day and "be sure" that he has a "copy to respond to."

The revelation adds a new dimension to exactly what Strampel — whose own history of inappropriate conduct at MSU was an open secret for years — knew about Nassar, and how early he knew it.

Strampel retired from MSU in 2018 and was charged in 2019 on two counts of willful neglect of duty. Strampel faced a third charge for felony misconduct in office, in relation to sexually-charged comments he made to female students who had approached him for career guidance.

But Strampel apparently wasn’t the only high ranking administrator who knew about Nassar’s dubious blood testing project.

In his email to Nassar, Strampel appears to reference that Nassar incorrectly believed his medical malpractice insurance policy with MSU would cover him for the blood testing.

"You stated that Dean Jacobs and Jeff Kovan informed you to cancel your own malpractice insurance and informed you that you would be covered for this activity by the university," Strampel wrote, referring to the college’s then-dean and another MSU physician. "Neither of these gentlemen confirm that this is their understanding."

Strampel continued that, according to former risk manager Patricia Fowler and former general counsel Bob Noto, Nassar was not covered by the university’s medical malpractice insurance policy for the blood testing at any point.

"You should immediately stop any activity with (USAG) until you determine that (1) you are covered by the USAG for this activity or (2) you obtain your own policy for this activity or (3) you can make the case that this activity is of benefit to the University and receive written authorization that you are covered for this activity," Strampel wrote.

Nassar did eventually answer the committee’s follow up questions, said MSU spokesperson Amber McCann. His suspension from human use research was eventually lifted, "to the best of our knowledge," she said.

For the three years following the committee’s investigation, Nassar’s research was overseen by a mentor appointed by his department chair and dean, McCann said. Furthermore, any research protocols developed by Nassar in that time frame were "submitted for scientific review before being submitted to the (UCRIHS)."

For Denhollander, the first woman to publicly accuse Nassar, the fact that these MSU officials apparently knew of the blood testing debacle raises questions about the university’s information sharing practices. She said she wondered if the MSU investigators who would later examine allegations of sexual abuse against Nassar knew about this earlier incident.

"It’s almost guaranteed that the individuals who heard initial disclosures of abuse never knew about this other incident that highlighted his refusal to follow informed consent and proper policy," Denhollander said.

Though MSU responded to several written questions for this story, it did not respond to a question asking if those at MSU who investigated allegations of sexual abuse against Nassar were aware of the blood testing saga.

MSU’s legal team did become aware of the blood testing issue after Nassar’s abuse was widely publicized, according to emails released amid thousands of long-privileged documents by the Michigan attorney general in September.

In 2017, as the university’s lawyers crafted their defense strategy for a looming barrage of civil lawsuits from survivors of Nassar’s abuse, they tasked an assistant general counsel with going through all of Nassar and Strampel’s paper files.

When she found the letters describing the blood testing and MSU investigation, she forwarded them to MSU’s litigation team, who were largely unaware of the saga, emails show.