Chloe, Carmen, Britney, Lillian, Ameenah, Tanya, Monifa, Dora, Sarah, Svitlana, María Teresa, Liz, Flor, Keira, Azya and Teresa.

These are the names of the women and girls featured in a 20-foot-wide painting on a Broad Art Museum wall, titled “A Long Line of Women.”

Surrounded by a lush environment, one woman climbs a ladder to pick a persimmon. Another holds her child while a girl next to her climbs into the bed of a truck.

One woman stands in the center of the painting, holding a sycamore leaf in her left hand. A stillness in the chaos of the scene around her, she locks eyes with the viewer.

Her name is Teresa Dunn.

Dunn is not just one of the many subjects of the painting — but also its creator. As an art professor at Michigan State University, Dunn's "A Long Line of Women" painting is featured in the Broad Museum's current faculty work exhibition.

The piece explores how people and their stories transcend across time and connect to the world around them, which is a persisting theme throughout Dunn's work.

Her own life has guided much of this conceptual framework, as her experiences as a Mexican American woman have often been shaped by interactions between identity and society. Now, Dunn aims to tell underrepresented stories, recognizing their value in her work as an artist and professor.

Always an artist

But Dunn never decided to become an artist, she says, because she always was one.

“I feel like I've always been a maker,” Dunn said.

She had a propensity for creativity as a kid, drawing and constructing mini towns from paper cut-outs. But art was never something Dunn considered for a career.

That was until her second year of college, when she realized majoring in math did not bring her joy. She couldn’t envision her future, which she said led to an existential crisis. And that led her to art.

With her parents' blessing, she started taking drawing classes because she “didn’t know what else to do.” And it just felt right, she said, “like home.”

“Everything in my being was telling me to stop and change direction, and when I changed that course, it just snowballed and everything fell into place,” she said.

Dunn changed her major to painting, which she said aligned with who she really was.

“The maker that I always was, since I was a small child, was being fully realized and felt,” Dunn said. “I felt like I was coming into the person that I was meant to be when I started taking the drawing classes and continued that creative path.”

A fascination with people and their stories

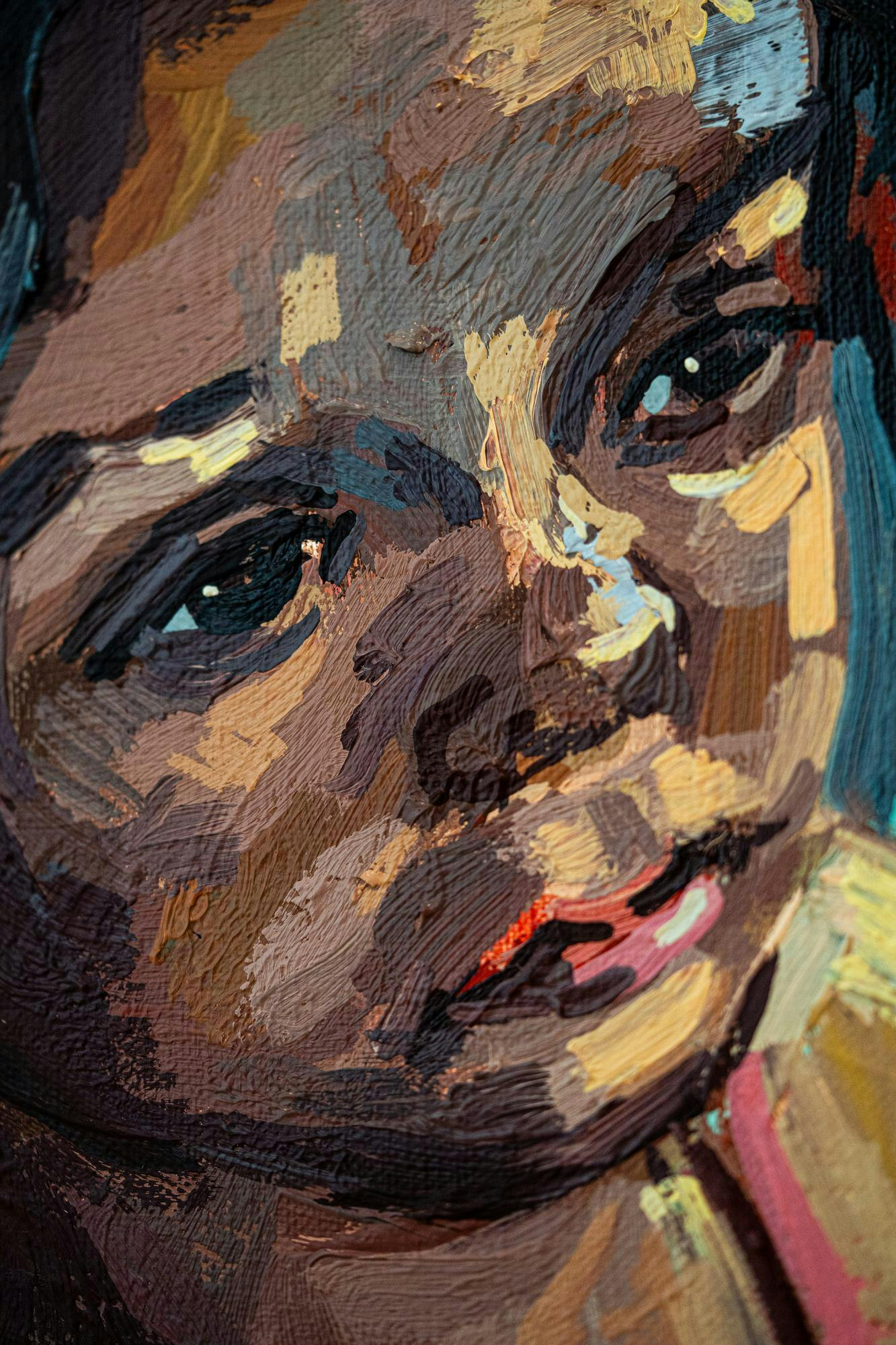

Her program at Missouri State University focused on the human figure. She quickly became enamored with painting and drawing people.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

“I loved portraits and just kind of thinking about the unique qualities of different individuals,” Dunn said. “What went into making a portrait isn't just about what people look like, but about so many other things that filter into their being.”

As it became impossible to separate a person from their story, Dunn grew to be a self-described visual storyteller.

This aspect of her work has only grown more prevalent over time. About ten years ago, Dunn started to deeply consider the meaningful nature of the stories she told in her art.

Her most recent art features people she knows — friends, family, students — and their stories. She considers them to be co-collaborators, a partnership that starts with her asking a question: “What story do you want to tell about yourself and your experience?”

This would sometimes lead to conversations that would last for hours.

“They're real stories, and the part that comes from me is thinking about ways to tell that story that is poetic that both hits on a personal level, but a broader social or cultural level,” Dunn said.

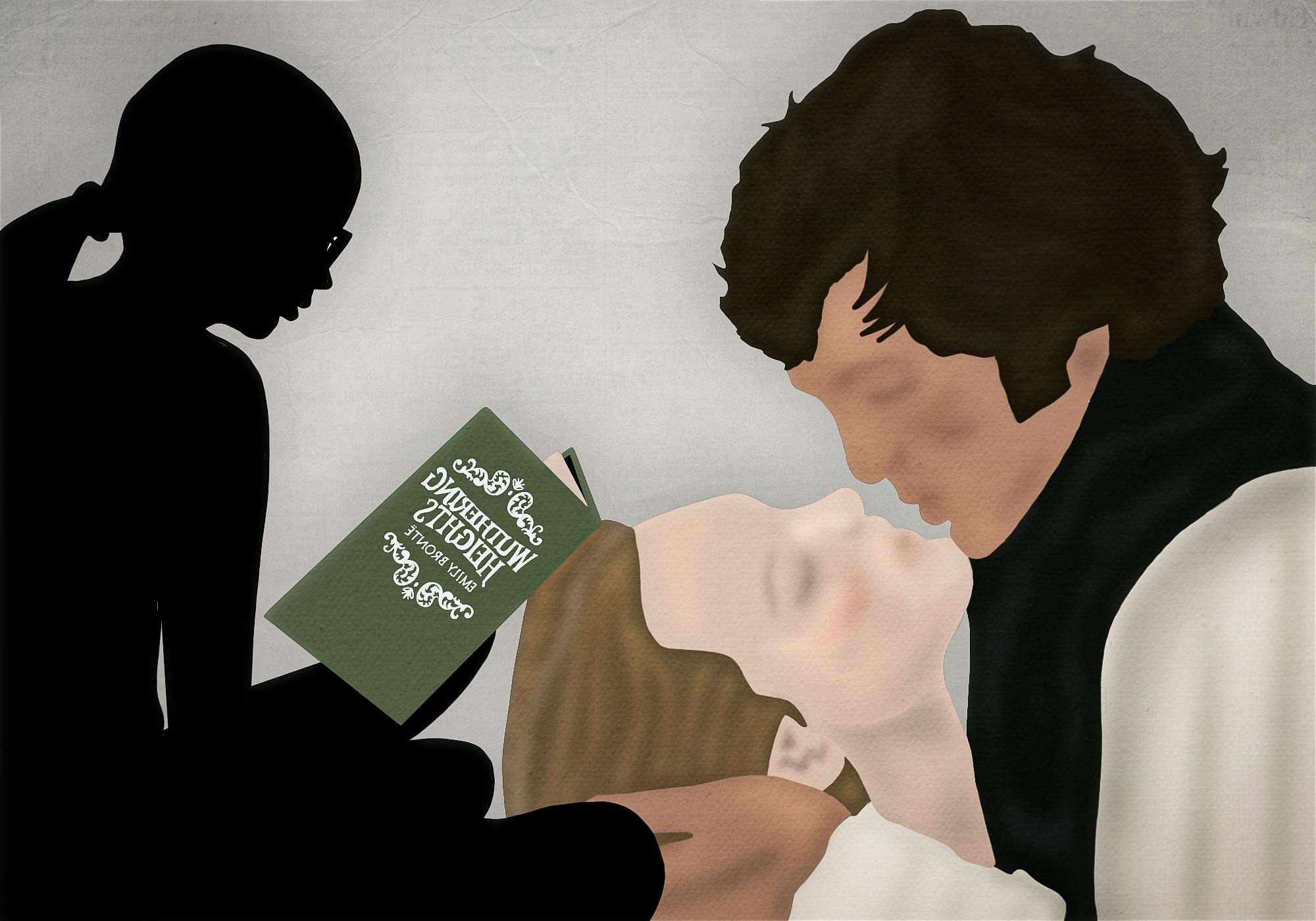

Because she said it’s impossible to capture someone’s story in a single moment, Dunn also began experimenting with the flexibility of time in her work. Her paintings can be experienced like movies or novels, she said, unfolding across time.

“What first interested me in people is that we're not just the physical,” Dunn said. “There's so many different levels of who we are as people, and some of that — like the complicating of the compositions, the big scale changes, the same person appearing multiple times in a painting, or weird spaces that don't quite make sense — are visual analogies for the complicated ways that we move through the world as complex human beings.”

Simultaneously, Dunn started to think about her own story, which has been heavily influenced by her background.

Art shaped by her experiences

Growing up Mexican American in a rural, predominantly white town in southern Illinois, Dunn struggled with feelings of belonging. Her skin was also a darker complexion than the rest of her family's, which she said caused strangers to assume that she did not belong. Dunn said this resulted in her developing a cognitive dissonance regarding her own identity.

Her family called her Teresita — her authentic self, she said. But when others tried to say the name, they pronounced it in a way that she said made her feel ugly and different, even if they didn’t intend to. When she left for college, she switched to Teresa, though it didn’t feel like her real name.

Dunn said she had to come to terms with these feelings as she entered adulthood. The “what are you?” question has never stopped. Looking “like somebody different” isn’t what bothers her — it’s the fact that other people care so much.

“It's a game of ‘You don't belong here. Where do you belong?’” Dunn said. “And that's the part that I still struggle with… I think that's something that I will probably wrestle with for the rest of my life.”

She explores these themes in her self-portraits. In one, she cures a molcajete, which acts as a double meaning for curing herself of the identity conflict she faced growing up.

“I feel like my current work is feeling more confidence in who I am, embracing myself, and being a person who lives in this middle space,” she said. “So many people who are immigrants, who have multicultural kind of experiences in their current lives and feel like they might be not a part of whatever that American dream is — that is the American experience.”

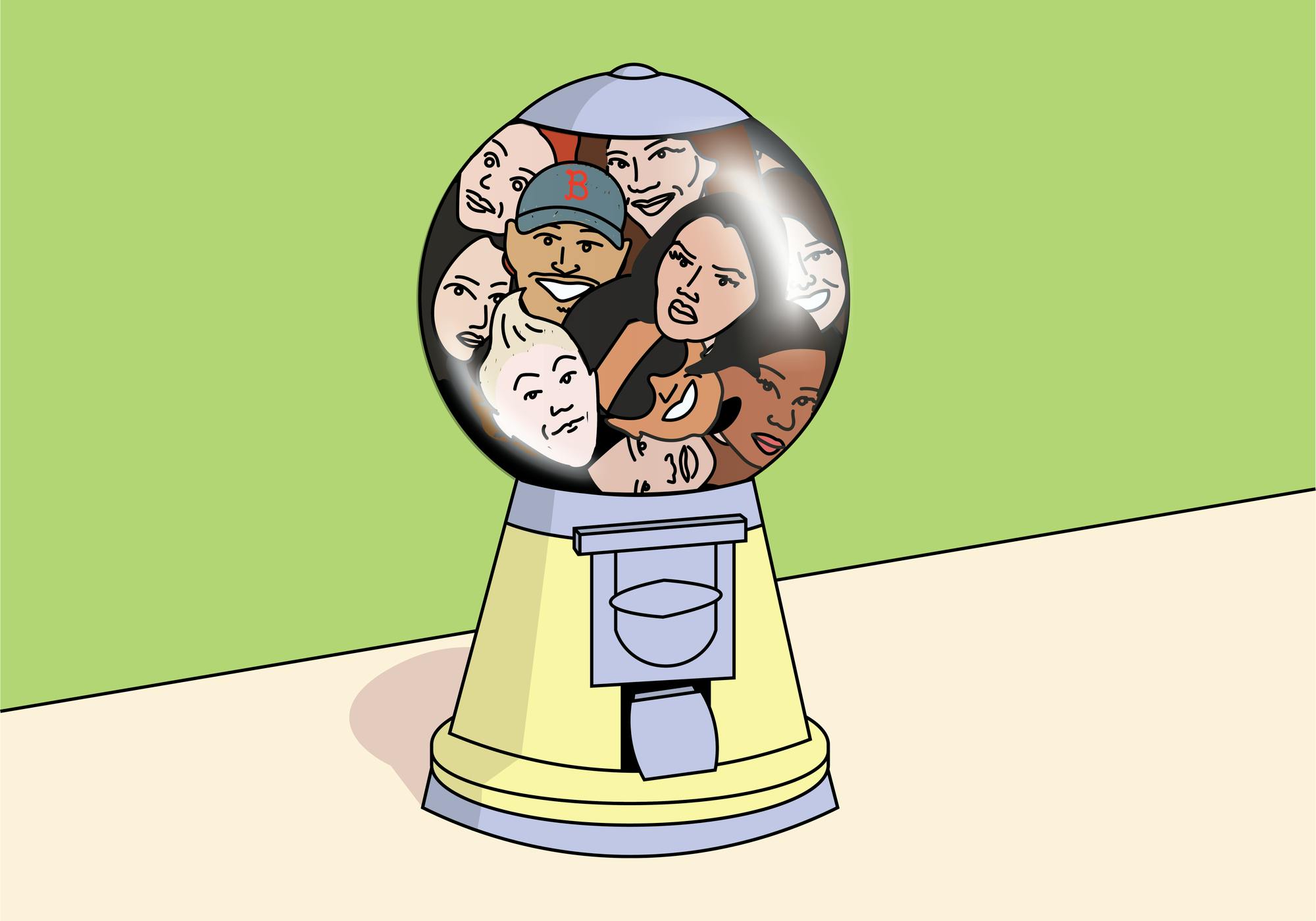

She embraces and prioritizes these stories in her work. Whether representing people of color, immigrants or people with multicultural backgrounds, those are the stories she wants to contribute to the cultural flow, which she said has a dominant, singular narrative.

“The American story is so broad and diverse and interesting, and I want to be able to tell the stories of people who may not feel like they fit neatly into that narrative, but really are an integral part of it,” Dunn said.

Creating 'A Long Line of Women'

As she spoke to more people, Dunn grew interested in the stories of the women she interviewed. She started to consider the connections between them, especially as she raises her own daughter in a world that she said often pits women against each other.

She had also just taken a 23andMe DNA test that traced her maternal line back to a woman who lived on the other side of the Bering Strait 24,000 years ago.

Dunn said this discovery hit her hard, and she began thinking about the women who came before her. She wove a line between them, not just along genetic boundaries, but also celebrating relationships between women as something that brings them together.

That’s how she arrived at “A Long Line of Women.”

The massive, four-panel painting features several women in Dunn’s life, including her maternal grandmother, mother and daughter. Dunn herself is featured three times at different stages in her life: in the first panel as the woman holding her daughter’s hand, in the second panel staring straight ahead, and in the third panel as a child in her mother’s arms.

The women are surrounded by lush greenery, which Dunn said represents fertility. This is not to be taken in the mere literal sense, Dunn said, but also as a representation of the fertile ground that women are as “valuable, critical propagators of culture and meaning in our societies.”

The piece is featured at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum as part of an exhibition of faculty work, where it will remain until July 21.

According to Dalina Perdomo Álvarez, a curatorial assistant at the museum, Dunn’s piece is crucial to the exhibition, which explores the relationship between fantasy and reality.

“I think ‘A Long Line of Women’ suggests that there are all these stories that we can know more about the woman in our lives,” Perdomo Álvarez said.

By showing these women, but not making their relationships to one another evident, the piece leaves the viewer wondering, Perdomo Álvarez said.

“It's very much like we're left wanting to know more,” she said. “But at the same time, it's kind of fantasizing this better world where women are recognized for their stories and honored for who they are, which is what Teresa's doing.”

Dunn said having her art accepted in shows like this one is validating — a feeling that was especially important when she first started in college.

Dunn has experienced imposter syndrome, which is a feeling of not belonging in a space despite success, throughout her life. That feeling has been exacerbated when entering predominantly white institutions like MSU.

Bringing her philosophy into teaching

This understanding is something Dunn carries into her teaching, as she aims to provide a space where all students can thrive.

“I want all of my students, regardless of their background, to feel valued, and that their voices, as different as they may be, are valued,” Dunn said. “They can realize their creative expression in ways that are unique to them, and there isn't a sense of hierarchy in my classroom of where you're from, and it's not a game.”

Dunn said she talks to her students one-on-one to understand who they are, their backgrounds, goals, concerns and what they want to express in their work. Her teaching philosophy is mutual respect, she said, like an exchange of information.

This has been especially crucial for Dunn as a professor of color. One of Dunn's former students, Jasmine Brocks-Matthews, said Dunn was the first professor of color she took an art class with.

“It felt like a weight was off my shoulders, like I could finally feel like I didn't have to walk on eggshells, and I can talk about certain topics that I knew that she was going to be able to relate to on some level,” said Brocks-Matthews, who graduated with a degree in studio art this spring.

Like Dunn, Brocks-Matthews’ work focuses on the human form and is inspired by her own experiences, with a focus on telling stories about Black women and bodies.

She said Dunn has taught her how to be unapologetic in her art.

“She's confident with her work, and she is not afraid to be vulnerable when it comes to telling these stories, which is exactly what I try to do now as a student,” Brocks-Matthews said.

Being a part of students' journeys is important for Dunn, too.

“I love being a part of the beginning of students’ journeys and watching them and helping guide them as they move through their freshman to their senior years, or even graduate school to the professional world,” Dunn said. “Being a part of that journey and helping provide them the tools that they need to be successful creative individuals is really rewarding and special to me.”

Dunn said helping others explore their creativity has been a meaningful experience, as teaching and engaging with students has allowed her own creativity to continue flourishing.

“I think it was actually the right path,” Dunn said, “because it really does resonate with me being a maker, being a painter, and then also teaching others and hopefully guiding them to meaningful creative lives.”