Over 2,000 security cameras, 551 motion detectors, and 5,400 electronic door-locks are nestled across Michigan State University’s sprawling campus.

The data they collect — from over 26,600 sources in total — all goes to one room.

In the university's new Security Operations Center, police monitor the campus 24 hours a day, 365 days a year on an array of video screens.

What they see is filtered through an AI-powered software capable of tracking a person or vehicle, counting the people in a crowd, or scanning for cars parked without a permit.

From their desks, they’ll be able to remotely lock and unlock doors or control elevators inside campus buildings.

The nearly $10 million project is a sweeping overhaul of the way campus is policed. The university has long had various sensors and security cameras, but they were never integrated into a central surveillance system.

The tracking software has been operational since February, though it’s unclear how much of campus is included. MSU police says the full campus will be integrated into the system in two to three years.

The work will connect MSU’s existing cameras and sensors to the new system and add hundreds of new ones.

While the project was announced before a campus shooting last year, the university boasted the plans in the weeks that followed. They said it was part of an effort to make students feel safe on campus again.

Now, as the first real details are emerging, student activists and security experts are growing concerned about the potential consequences of the massive surveillance effort.

They see “security theater” — promising safety but delivering surveillance.

The system would be largely unhelpful in the event of another active shooting, they say.

The expansion of police power it brings — especially with the AI-powered technology processing the data — is also likely to disadvantage marginalized students.

And, the technology’s ability to monitor student protests raises concerns among student activists, who already distrust MSU police over decades of surveilling student speech.

These details of the system are becoming public for the first time through public records requests. A trove of documents obtained by The State News — including vendors’ bids and MSU contracts — give the campus a first glimpse into how exactly they’re being watched.

Ineffective in a potential shooting

MSU’s Security Operations Center is one of many “campus safety updates" the university has boasted following the shooting. But, students have expressed concerns about such measures from the start.

A week after the shooting, campus climate organization Sunrise MSU released a statement urging students to “resist calls for increased police presence and ‘security’” in the wake of the shooting.

“We were worried by what we were seeing at the time: more calls for police on campus, locking doors, more cameras,” said Jesse Estrada White, a student activist and comparative culture and politics junior who led Sunrise when it released the statement.

What’s happened since — the quiet implementation of the new surveillance system — is more severe than he could have imagined, he said.

“It would have been hard to predict that MSU would turn campus into a global panopticon,” he said, referring to a type of circular prison with constant surveillance from a central post.

Estrada White said that hasn’t made students feel any safer. The tech doesn’t address the “root problems” that cause shootings, such as easy access to firearms, he said.

“The reason we had a shooting wasn’t because there weren’t enough police on campus, and it’s not going to stop another event like that from happening,” Estrada White said. “It didn’t seem like any of it really makes us safer.”

Experts in the technology and mass shootings agreed.

“There’s nothing that explains to me how this would stop a shooting,” said Conor Healy, who researches security systems at the Internet Protocol Video Market, a security and surveillance industry research group. He reviewed the service agreements between MSU and the relevant vendors for The State News.

“If you, God forbid, intend to shoot a bunch of people on a campus, you usually don’t care if there’s a license plate reader,” he said. “A mass shooting scenario is generally not something technology can stop.”

At best, increased camera coverage could only help track a shooter, not prevent it from happening, said Odis Johnson Jr., a professor at Johns Hopkins University who has researched school shootings and racial inequities in policing.

“You're going to have to think about something else if you actually want to prevent these acts from occurring in the first place, and the only prevention for that is sensible gun control policy,” Johnson said.

MSU bought the new surveillance system from Moss Audio Corporation, a Grand Rapids firm that integrates technology for businesses. They don’t make any of the software or hardware MSU is using, instead buying and installing it for the university.

The software comes from the Montreal security firm Genetec.

Moss did offer MSU a more shooting-specific feature that could be used in the security operations center, according to the bidding documents obtained by The State News.

They advertised Genetec’s “ShotSpotter gunshot detection system,” which uses an array of microphones to detect the sound of gunshots and alert police to it.

That tech was never purchased, according to the documents.

MSU Police Director of Public Safety Operations John Prush said the university did discuss adding gunshot detection capabilities but ultimately decided against pursuing it.

MSU police could add similar technology from outside vendors should they change their mind, he said.

“No, not at this time are we planning it,” Prush said. “But, I don’t want to say that we’re not not planning it.”

ShotSpotter systems have been heavily criticized in recent years, with some major cities - including Detroit - embroiled in debate over the technology's inaccuracies and effectiveness.

Even if the tech worked perfectly, it wouldn’t do much to help in an active shooter situation, Healy said.

“If there’s a shooting happening in a public place, you know, because there’s someone with an AR-15 shooting at people, you hear about that quickly,” he said. “So, even if the tech works, you gain a couple seconds.”

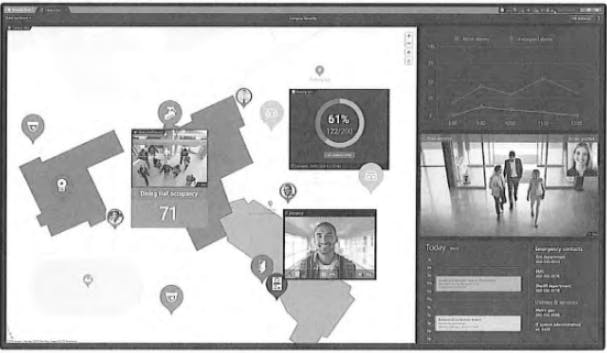

A mockup of MSU's new campus surveillance system created by the vendor. Here, a supposed MSU police employee watches who enters and exits a building in real time. Obtained by The State News through a public records request.

Protest tracking fears follow troubled history

The software also has a sophisticated system for tracking crowds.

“If something were happening and people started to gather, the system would be able to say ‘I detect multiple people here,’ and we would then know about it,” Prush said.

For student organizer Savitri Anantharaman, that’s worrisome.

“It’s going to be used against student activists and groups protesting on campus,” said Anantharaman, a member of Sunrise MSU and James Madison College Women of Color.

The new technology is being implemented at a pivotal moment for campus activism. Nationally, colleges and universities are testing the bounds of campus speech restrictions as they encounter activism related to the Israel-Hamas war.

Last week, the University of Michigan announced a draft policy that would harshly punish demonstrations at university events. Some student activists have said it infringes on their rights.

Asked whether MSU police would use the crowd-tracking technology to monitor student speech and demonstrations, Prush said “not that I can foresee.”

Student organizers said they don’t trust MSU police to stick to that, given the department’s long history of surveilling student speech.

In 2001, an undercover MSU police officer posed as a student in an anti-capitalist club for months, according to State News articles from the time. In 2018, MSU sent undercover officers to protests of a prominent white nationalist who spoke on campus, according to a report from The Intercept.

Until recently, MSU police also used open-source AI softwares to monitor social media for discussion of campus protests, according to documents obtained by The State News.

Notably, they tracked a 2019 campus demonstration organized by the animal rights advocacy group People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA.

An Oregon court recently ruled that similar use of open-source tracking softwares to keep track of PETA protests at Oregon Health & Science University amounted to “illegal surveillance.”

Because of that history, Estrada White said he doesn’t trust MSU police to use the new technology ethically.

“If they’ve done it in the past, they’ll do it again,” he said. “It’s just a matter of how badly they want to shut down the protests.”

Even if MSU never uses the technology to track demonstrations, the mere existence of it could have a chilling effect on student activism, experts said.

“Maybe you don’t want to go to a public protest because you’re worried the university could later use the (information gathered by the new surveillance system) against you,” said Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, an American University law professor who studied the legal ethics of similar systems for his book, “The Rise of Big Data Policing.”

While the system MSU purchased doesn’t specifically purport to monitor or regulate protests, some of the features could be applicable to that, said Healy, the researcher who read the contract.

“Theoretically, they could potentially use this system to monitor student groups putting together protests,” he said. “It comes down to how they use it, rather than what it does.”

Asked about the protest tracking concerns, Prush said “I would ask you to talk to the chief of police, I’m just the director for public safety operations.”

MSU police declined to make interim vice president and chief safety officer Doug Monette available for an interview.

Estrada White said he hopes other campus activists won’t be deterred by the “scare tactics.”

“They’re not gonna be able to put on this little show, this theater, and stop us,” he said. “They’re not gonna scare us into a little hole and keep us from coming out. If anything, this just proves we need a much bigger movement on campus.”

The surveillance system itself should be the subject of campus protests, Estrada White said.

“This system is just another reason why we have to keep doing it,” he said.

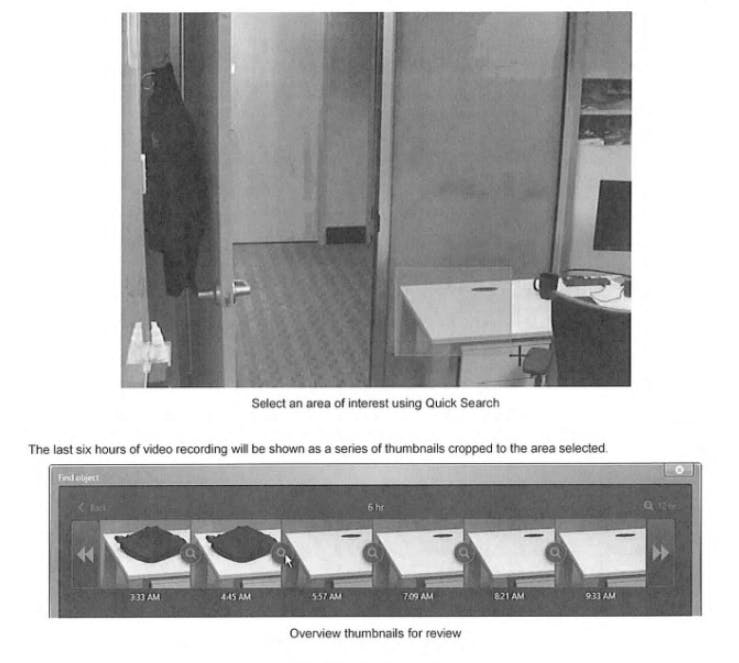

A demonstration of MSU Police's new object tracking technology created by the vendor. The feature allows MSU Police to view the history of an area or object. Obtained by The State News through a public records request.

Surveillance brings racial disparities

More and more schools are turning to surveillance in response to fears of school shootings, said Johnson, the expert, who’s also the executive director of the Center for Safe and Healthy Schools at Johns Hopkins University.

Implementing those systems has had a major cost, according to a study Johnson led in 2021.

“There are racial differences in whose behavior is deemed suspicious through surveillance,” he said.

His research — based on data from over 6,000 high school students in the U.S. — found that increased surveillance exacerbates racial and ethnic disparities in who is punished and who isn’t.

High schoolers facing discipline as a result of their activity being surveilled are four times more likely to be African American. Students who came from low-income and single-parent homes faced similar disparities, Johnson found.

Johnson says he expects the same disparities to appear at MSU under an expansion of its surveillance capabilities.

“A big concern is that these systems, when put within higher education environments, will lead to disproportionate honor code violations, code of ethics violations and some type of punishment,” he said.

Estrada White, the student activist, said that was a fear from the start.

“Our fear was that any increase in policing and securitization of campus would not actually make students safer, but would increase biases that already exist in our police department and make Black and brown students feel less safe,” he said.

Anantharaman, the other activist, said the increased police capabilities will put marginalized students at further risk of police violence.

“That’s not the campus we're trying to create,” Anantharaman said.

Prush said MSU is more focused on physical data, like tracking vehicles and object detection. He said the current system isn’t “there yet” with software that could show biases.

“We’re not at a place where we will have to review the systems for that capability to say if it has a bias or a slant,” Prush said. “It would be something that’s going to come in the next few years, and a policy will have to address it.”

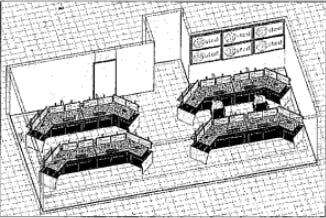

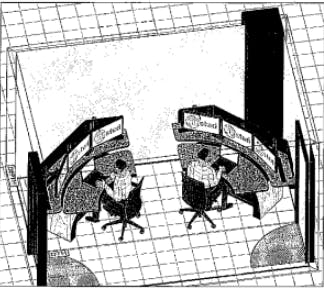

A mockup of MSU's new Security Operations Center made by the vendor. The university refuses to show the inside of the center or disclose its location, making these drawing the only glimpse into the centralized security hub. Obtained by The State News through a public records request.

License-plate tracking and legal concerns

The new system will also usher in campus-wide automatic license plate recognition, allowing police to track and monitor vehicles.

MSU police already uses license plate scanners on parking enforcement vehicles. They scan plates as vehicles drive through parking lots, seeing if any vehicles lack the required permits or payments, Prush said.

The sophisticated system resulted in nearly 100,000 tickets in 2023. Some students have attempted to subvert it with an app tracking the parking enforcers movements.

The new system could track license plates as they enter or exit lots, track specific vehicles throughout campus, and even create logs of where “hotlisted” vehicles have been throughout the day.

It would be useful for parking enforcement, but could also be applied to a much broader tracking of people, said Healy, the researcher.

Such systems are illegal in some jurisdictions. In Michigan, license plate recognition is currently being regulated in individual communities, with municipalities across the state debating civil liberties concerns.

In 2013, lawmakers attempted to regulate the issue statewide.

Sam Singh, a Democratic state senator whose district includes MSU, introduced a bill that would only allow law enforcement to track license plates during felony investigations, not as a part of widespread everyday surveillance.

The bill was never passed.

Singh said Tuesday that he believes the legislature may soon move on the issue again. Lawmakers have recently discussed researching the issue and drafting a new bill, though nothing has been introduced, he said.

The lack of clear regulation of the license plate tracking speaks to a bigger issue, Healy said — lawmakers cannot move as quickly as the technology.

The security vendors are releasing new products every year as regulation falls further and further behind, he said.

“There’s very little regulation on this, especially at the state level,” Healy said.

“None of it makes me feel safe.”

MSU’s new surveillance capabilities have experts and students concerned about privacy on campus.

Surveillance systems like the one at MSU are often a form of “security theater”: a possibly comforting notion for students and families that, in practice, couldn’t stop tragedies like the shooting, said Ferguson, the law professor and author.

In exchange for that limited comfort, he said students will give up some of their privacy and civil liberties.

“They say it’s going to protect you, but what are the costs of that protection?” he said. “What’s it like to live on a college campus where police are watching you and keeping track of your youthful indiscretions? … I’m quite thankful we didn’t have those camera systems when I was in college.”

A few measures MSU police procured could provide some protection for privacy.

One feature gives MSU police the ability to censor moving objects such as vehicles and people in real-time, according to the contract.

That masking can be undone by the operators however, according to the contract.

Asked about plans for the usage of the feature, Prush said “I don’t recall if that’s a service we’ve procured.”

The university is also the sole owner of data compiled by the security operations center. Outside vendors would only have access to data if that was needed during installation, Prush said.

But overall, the broad expansion of MSU police’s power and capabilities leaves some feeling uncomfortable, not safe.

“For a lot of students, more police, cameras that track us wherever we’re going, locking doors to the places we used to study and hang out and eat food, that sort of stuff doesn’t make us feel safer,” said Estrada White, the student activist. “It just keeps us in this climate of fear and anxiety about it happening again, but does not challenge the root problems that cause it.”

Anantharaman, the other activist, agreed.

“I feel strongly that all these measures put in place post-shooting are a form of theater,” she said. “None of it makes me feel safe on campus.”