Content warning: This article contains description of the Feb. 13 mass shooting that some may find upsetting.

Michigan State University professor Marco Díaz-Muñoz was teaching when he heard three loud sounds coming from the hallway. He had never heard gunshots in person. He thought maybe a transformer had blown.

Suddenly, a man was standing in the doorway at the back of the class.

“Shooter!” a student yelled.

Three minutes of chaos ensued.

Díaz-Muñoz remembers what came next: “shooting and shooting and shooting and shooting and shooting.” Each shot sounded like an explosion. He saw sparks coming from the gun. Díaz-Muñoz said he felt the room’s temperature drop instantly, like he was in a freezer.

“I felt as though there was a connection between the terrible violence and a terrible coldness, lack of compassion, anger accumulated beyond belief and just letting all that up in my classroom,” Díaz-Muñoz said.

Then the gunman left. Díaz-Muñoz told his students to break the windows and escape. Others tended to wounded classmates or were frozen in place.

Díaz-Muñoz was terrified that the man would come back, so he threw himself against the door at the front of the room and held the knob. He squatted so he couldn’t be seen through the door windows.

He still hadn’t wrapped his head around the fact that it was real. He tried to tell himself it was a false alarm or fiction — that everyone was acting.

“I kept telling myself to deny that this was happening because accepting that it was happening was to accept that my students were dying and were actually being harmed,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “And that was a very difficult truth to accept. And then it was true.”

As he held the door knob, he felt immense terror. He knew it could easily be shot open. He prepared to die.

“If I'm gonna feel a bullet in a minute and 10 seconds then I'm gonna feel a bullet,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “Let me prepare for it. If I'm going to die, I'm going to die. That was another thought in my mind. This may be my time.”

After what he said felt like an eternity, he saw two police officers and opened the door. That’s when he turned his attention to the wounded students. He wanted to help them, but he knew his actions might hurt them more. He said he kept insisting that the paramedics help them.

“They’re gone,” someone said.

He couldn’t believe it. As he was escorted out of the room by the police, he continued insisting that they help the two in greatest need, Alexandria Verner and Arielle Anderson. The paramedics told him they would do the best they could. He started crying as he was ushered to the Broad Art Museum where he spent the next several hours in lockdown.

During that time, Díaz-Muñoz said his memories shifted. He felt like the memories belonged to someone else, or they were from a movie. He now knows that his psyche disassociated immediately following the shooting. His brain separated his conscious from his subconscious to protect him from the trauma. He said it was like putting the painful images and memories in a closet and shutting the door.

When he went home, he felt like nothing had happened, but he knew his life would never be the same.

“Nothing in my home had changed, yet something had changed,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “What I experienced changed my life, and I knew it was negative. I knew it was terrible. The truth was terrible. To accept it, it was terrible. So the only way to not accept or try to think of that reality was to make myself sleep (using sleeping pills).”

That was two months ago. The pain is still there, but Díaz-Muñoz has worked to process it.

He now sleeps more and attends therapy. Going to the gym has also been critical to his healing. But these moments of solace have been shattered at times. Occasionally, a memory invades his dreams. Sometimes a sound or sight triggers that closet door to open and the trauma comes flooding back in.

One time, a man walked in the gym’s front door and it reminded him of the gunman entering his classroom. He became paranoid that the person had a weapon, so he studied the exits to determine the best escape plan and tried to make himself invisible.

Díaz-Muñoz said that’s not like him — that he’s never afraid. But then it happened again.

He heard screaming at the gym. It was a group of people laughing and screaming with joy, but the sounds reminded him of his students screaming. He was terrified. He hid and tried to find a pipe to use for protection.

He arrived safe at home each time. And although the fear was over, the pain stayed. He said he feels it every day.

It is because of his pain and grief that Díaz-Muñoz returned to class. He said he felt lost and he realized that he needed to see his students. He compared them to a wooden board floating in the ocean that he had to hold to stop from drowning.

“Those few minutes that we were experiencing (that) together makes one feel as though, in the case of my students, they kind of became part of my family,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “I suppose in some ways, I became part of theirs. Because we were experiencing that same thing together and because some of them did not survive, I felt this great need to hold on to something.”

Additionally, Díaz-Muñoz wanted to return for the sake of his students, who might otherwise be forced to transfer to a class full of strangers. He also did not want graduating students to have their experiences at MSU end with Feb. 13. He said he wanted to provide them with the positivity to move forward.

So, on the following Sunday, Díaz-Muñoz returned to campus for the first time. He and a colleague went to Wells Hall, but when he looked down the dark hallway full of classroom doors, he didn’t feel safe.

The following day, he returned to teaching. His classes were moved to Bessey Hall because MSU had shut down Berkey Hall for the remainder of the semester. Díaz-Muñoz said he used to request Berkey room 114 every semester because he liked its old technology and big windows. Now, he avoids looking at the building and he said he never wants to teach in room 114 again.

When he saw his students’ faces and received their hugs, he became emotional.

“I wasn't mistaken when I felt that they needed me, and I needed them,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “I think they needed to see me alive and I needed to see them alive, tangibly sitting there. That was a moment of healing.”

That week, Díaz-Muñoz shared his feelings with the students before slowly easing back into coursework. He adjusted the schedule and expectations and allowed students to attend class virtually. The class is still about half the size as it was. He said there are several students he hasn’t heard back from and others who transferred classes because being there was too painful. Díaz-Muñoz continued teaching new content in a balanced way so students felt like they learned and earned their grades.

But the hardest part of returning to class was that Verner and Anderson were not there. He said he felt haunted by their absence.

"That was the hardest thing for me to not have the students back,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “I felt guilty that night that their lives were taken away, but I was still alive. I know a lot of people say you don't have to feel guilty, but one does … They were just starting their lives. And (thinking about) seeing them and me trying to help one of them, but I decided not to move her anymore because I thought I was perhaps hurting her more, haunted me for days and weeks … That's why I didn't want to be awake. I slept and slept. I didn't want to think of it.”

Díaz-Muñoz said he will always remember Verner and Anderson. At the beginning and end of each class, students lined up at his desk to sign their name for attendance and he used that opportunity to interact with them. He asked them how they were doing or joked about wanting their autograph. He said he remembers joking with Verner and Anderson and them laughing and telling him to “have a good weekend.”

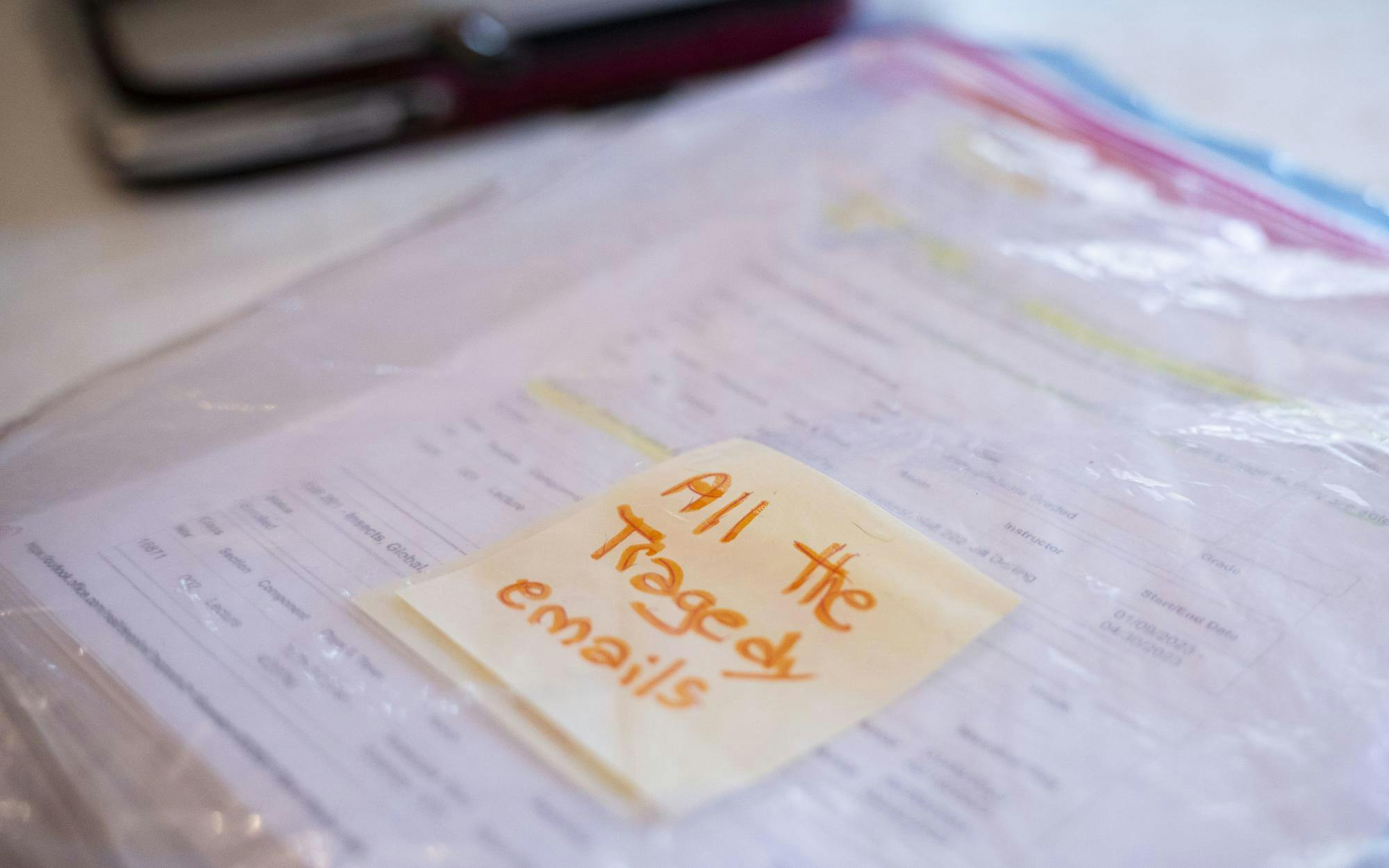

One of the ways Díaz-Muñoz managed his grief was the outpour of support. Following the shooting, his colleagues brought food to his house for three weeks. He also received food from stores and strangers, as well as countless emails and artwork. One person sent him a box of origami cranes, which he took to his students.

Though these actions have given Díaz-Muñoz some peace, he cannot help but feel angry. He said during the shooting, the hell that was inside the shooter’s head transpired inside the classroom. Because of this, he wonders if the shooting could have been prevented.

“Could this person have been different, had mental health services been there sufficiently to aid this person?” Díaz-Muñoz said. “Had society been more accepting of people who are not in the best of shape, emotionally, mentally or physically, could this person have been different?”

Díaz-Muñoz said he believes the shooter is not the sole source of blame. He said in a society where the rich get richer as poor people remain in poverty, where militarism and guns are valued and where mental health resources are inaccessible for some, this is the result.

“I think that to point to him alone is to miss something that is terribly wrong in this society, and it's how little we care about people who are on the margin,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “The problem wasn't just that person. That person was simply a symptom where everything that was wrong converged and this person blew up.”

There have been dozens of mass shootings since the one at MSU two months ago. Each time, Díaz-Muñoz feels angrier at what he said was inaction by politicians.

“Everybody wants to blame somebody else so that they don't have to change or modify their lives,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “Those who own guns want to blame something else so the laws don’t change to affect them. Everybody's putting themselves first, instead of putting the other first. The day that the majority of us in this country put (others) first … things will change.”

Díaz-Muñoz said because he grew up in Costa Rica, where the military was disbanded in 1948, he did not grow up in a gun culture. He does not believe in defending himself from other guns with a gun. In fact, experiencing the shooting made him more adamant against owning a gun. There must be fewer guns to reduce violence, he said.

Additionally, he said the U.S. needs to stop thinking of itself as the most advanced society and instead draw from other countries that don’t have high levels of gun violence. Díaz-Muñoz said Americans must overcome their arrogance and realize, “the world doesn't rise and set in the U.S.” Only then, he said, can people imagine a better future.

“Because I grew up somewhere else, I also can see how this country could be different in a way that those people who are so clinging to their guns cannot see,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “I can see things being different… But you have to imagine that first, you have to imagine that it is possible. So what I'm proposing where it was said, and I'm not proposing sharing is not impossible. It's only possible for people who hate change. But change needs to happen.”

Díaz-Muñoz said this message is one of the most important things he can share with others. They must protest and challenge gun policies because anyone’s life can be shattered at any moment due to gun violence, he said.

Feb. 13 was not Díaz-Muñoz’s first experience with a threat on campus. In 2021, campus went into a lockdown due to the threat of an armed man. He didn’t know how to handle the situation, but his students were prepared. They had spent their whole lives learning how to prepare for a shooting, so they barricaded the door, turned off the lights and hid.

“I feel sad for my students who had to grow up seeing these things, who had to grow up going through drills about mass shootings,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “I thank God so much that I grew up in a safe place … I became an adult without any of those fears.”

Since the shooting, Díaz-Muñoz has constantly retreated to his childhood memories because they remind him of peace. He said remembering his love-filled childhood has allowed him to survive the present.

But as long as people still have access to guns, he still feels unsafe. He said it is a “bizarre mirage” to believe any amount of walls or guns could protect MSU. Instead, he holds onto his belief in God, who he believes determined his fate during those three terrifying minutes on Feb. 13.

“(I feel) that there's something greater than me that protects me no matter what,” Díaz-Muñoz said. “And if I no longer have anything good to give to this world, maybe it's my time to go, and my hour will come.”

Díaz-Muñoz said he is willing to risk the arrival of, “his hour” if it means he and others can claim their lives again. During the first week back with his students, they discussed shedding the fear. Throughout the past two months, he has shared his experiences with them — the moment of fear at the gym, the exhaustion, the grief, the healing, the joy and the anger.

Now, Díaz-Muñoz nervously anticipates the end of the semester, which is less than a month away. He doesn’t want to say goodbye to his students. He said those three minutes they experienced together changed their lives. He contemplates what he will say to them, how he will capture his grief for Verner and Anderson and Brian Fraser.

And he wonders how he will say goodbye to the class that was like the board floating in the ocean he held to stop from drowning.

“I will never forget this class," Díaz-Muñoz said. “They'll stay in my mind because we were marked by that experience and I'm sure they'll never forget their professor ... We all felt the pain of the losses of the lives of those two students and the pain of those who were injured … I know letting go of these students will be difficult … and I'll tell them, ‘I'll never forget your faces — you’ll always be with me.'”