Content warning: This article deals with sensitive subjects surrounding eating disorders. The National Eating Disorders Helpline can be reached at (800) 931-2237 on Monday-Thursday from 11 a.m.-9 p.m. and on Friday from 11 a.m.-5 p.m.

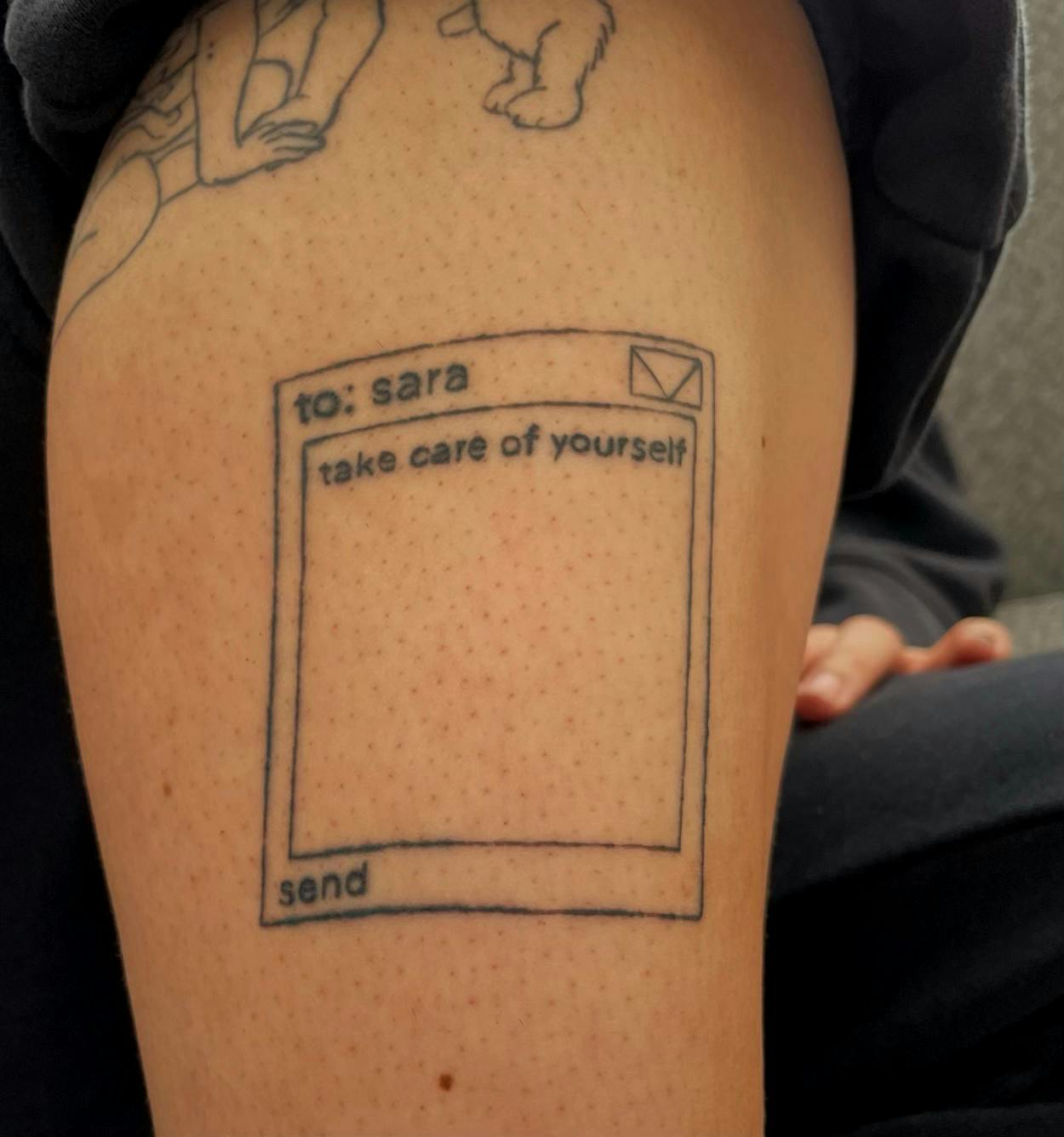

Sara Tidwell's right shin, where she has a still-healing tattoo of a quote – "take care of yourself" – in an unsent message box. Art done by Angie Hickey, who works at Old Soul Tattoo Club in Keego Harbor, Mich.

Content warning: This article deals with sensitive subjects surrounding eating disorders. The National Eating Disorders Helpline can be reached at (800) 931-2237 on Monday-Thursday from 11 a.m.-9 p.m. and on Friday from 11 a.m.-5 p.m.

I didn’t realize I’d been dealing with an eating disorder my entire formative life until I was 20.

I look back at things that were normal to me at a young age and want to cry. Why did my mother tell me that when I was hungry late at night, it was best to curb the cravings by chugging a glass or two of water? What was, what is, so bad about children wanting to eat at 11 p.m.? She scared me into thinking that I would gain “unnecessary weight” if I snacked right before I went to sleep.

I would eat one meal a day, leading me to binge everything and anything I could find when I got home from school or when I got to my five hour shifts at Taco Bell. I would ignore my hunger cues until I no longer knew what hunger felt like because my stomach stopped growling. My mood plummeted, ripping apart my most important relationships. I was always tired, losing hair, seeing spots or TV static any time I stood up. I was going off test results from 2005 that said I was allergic to dairy, wheat and gluten, trying and severely failing to avoid those food groups and then ending up miserable after eating them because my stomach was doing figure eights.

I was under 100 pounds until I was around 16.

I would get all kinds of comments, some talking about how they wish they looked like me because I “looked good” – I was literal skin and bones – and others talking about how I needed to put some meat on my bones because I was a “toothpick” and it was “unattractive.”

I remember the day that I stepped on the scale in my parents bathroom and watched as the blinking numbers finally landed in triple digits. I was so proud of myself for reaching this milestone.

I never felt that kind of pride over weight-gain again. I remember I put on a few pounds in my freshman year of college, reaching around 115 pounds – the mythical, but all-too-real freshman 15. My mother said that wasn’t good, even though she too weighed 115 pounds, and my sisters would joke, calling me chunky or pudgy. So I lost the weight as fast as I could, going to frat parties and drinking on an empty stomach, skipping going to the cafeteria in Akers because I didn’t feel like going, all to wake up the next day feeling weak and fragile.

I fell back to 100 pounds at 19 years old.

It wasn’t until the pandemic started and everything went into lockdown that I realized I needed to get real and total control of myself back. I didn’t know when I’d lost it, but I was withering away at an alarming rate, throwing up after every meal out of pure anxiety and obsessive, intrusive thoughts. For someone with emetophobia, I was over the toilet bowl quite often, and the compulsive repetition of my brain telling me anything I did not buy or cook myself was drugged is still something I’m dealing with today – I’m starting to think it’ll never end.

I sat down with a provider in the MSU Nutrition program during summer 2020. She probably doesn’t think she left an impact on me because I honestly never followed her advice and strict meal plans, but she did. In more ways than one.

I was able to start seeing food as a friend, not a foe; I was able to recognize hunger cues again and I actually sobbed when my stomach growled for the first time in years. I got put on medication for my sleep struggles due to anxiety that, in turn, revived my appetite from below the grave. I didn’t have a scale in my apartment, so I couldn’t religiously check how much I was gaining, but I knew it was quite a bit because one day 20-year-old me could no longer get my thighs in a single pair of the jeans 15-year-old me owned and wore.

I went shopping for jeans for the first time in five years when I was out in Hartford, Connecticut summer 2021. Becoming a size four after being a size zero from the start of puberty was difficult, I won’t lie, but it was also freeing as I started to realize that clothes were made to fit my body, my body was not made to fit clothes.

Eating disorders are complex, psychological conditions that affect people of all heights, weights, races, ages, sexual orientations, gender identifications, socioeconomic statuses, etc. They are not one size fits all. There’s anorexia, bulimia, binge-eating and more. Some can even co-exist. There’s phobias, obsessive calorie counting, fear foods and compulsive exercising. There’s fake “clean-eating” and social media trends that draw an uproar of competition in the community.

“Eating disorders are so often misunderstood, I think, because of the way they’re traditionally portrayed in the media,” Anne Buffington, the nutrition program coordinator for MSU’s Health Promotion Department, said. “The messages a lot of times that individuals are receiving – and again that’s not that this is the only contributing factor, there are many of (those). We have a toxic diet culture that we are living in, that surrounds us, and that diet culture tends to value … appearance, weight and shape above health and well being. … All (a diet culture) does is contribute to weight stigma, marginalize certain populations and add pressure.”

Having an eating disorder is like doing a 1,000 piece puzzle by yourself and recovery is different for everybody. For some, it can take mere months to see the light of day again, while for others, like myself, their struggles can span over multiple years. It’s hard to want to get better when your brain refuses to see a problem with your lifestyle.

The peak age of onset for eating disorders is between 12 and 25 years old, so college students fall in the vulnerable range at a higher risk of showing signs and symptoms, Buffington said. You cannot determine if someone has an eating disorder just by looking at them, she added.

The services Health Promotion offers intertwines with other MSU entities under the umbrella of MSU Student Health and Wellness. Within Health Promotion, students are able to seek out individual nutrition counseling. You do not need a referral from a doctor to undergo nutrition counseling here, but Buffington recommends that students work with a professional team to address and meet recovery goals, not just a single outlet – for example, MSU Counseling and Psychiatry Services or Olin Health Services.

If a student would like to set up an appointment with MSU Health Promotion, they can call the Student Health and Wellness scheduling office at 517-353-4660.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.