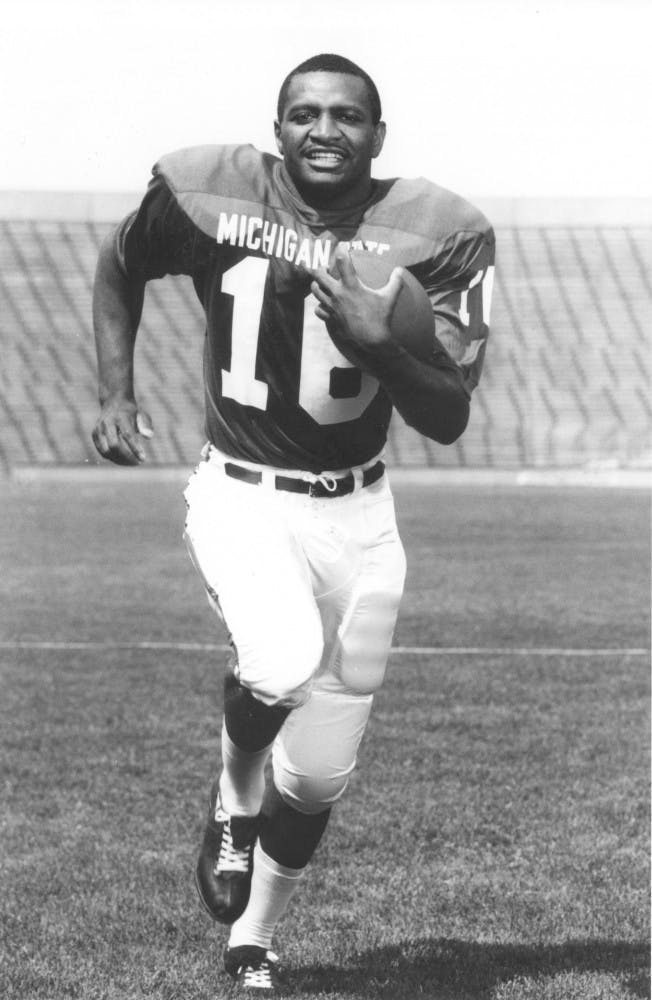

Jimmy Raye couldn't believe it.

The former MSU quarterback received a call from Athletic Director Bill Beekman, who told him he’s a part of the Spartan Athletics 2018 Hall of Fame class.

Jimmy Raye couldn't believe it.

The former MSU quarterback received a call from Athletic Director Bill Beekman, who told him he’s a part of the Spartan Athletics 2018 Hall of Fame class.

Raye, 72, thought he didn’t do enough on the field during his tenure in East Lansing. That made the phone call from Beekman more surprising.

“I was at a loss for words really,” Raye said before his induction at the Wharton Center Sept. 27. “When I did summon some ability to be coherent, I thanked him. I immediately got off the phone and I called (former MSU fullback) Bob Apisa, my buddy — two 72-year-old men crying on the phone out of joy was not fun to see.”

The Fayetteville, North Carolina native played for three years at Michigan State, spending the 1964 season on the bench since the NCAA didn’t allow freshmen to play. This allowed Raye to get acclimated with an integrated society — something he never experienced before.

“I never played against white players, I never had white instructors, professors and colleagues,” Raye said. “All of that was new to me. ... We had an opportunity to grow into the environment and see what it was like, and stumble and get picked up and have a chance to succeed.”

In the next three seasons from 1965-67, Raye completed 107-of-232 passes for 1,733 yards, 15 touchdowns and 18 interceptions, while rushing 244 times for 929 yards and nine touchdowns, according to the website sports-reference.com

He helped lead the 1965 team to a 10-1 season, a national championship and a spot in the Rose Bowl, in which MSU lost to UCLA 14-12.

“We had one of those days out in Pasadena, California that we’d like to forget,” Raye said. “That one cut pretty deep.”

Raye then led the Spartans to a 9-0-1 season in 1966, completing 62-of-123 passes for 1,110 yards, 10 touchdowns and eight interceptions, while carrying the ball 122 times for 486 yards and five touchdowns.

The 1966 season also featured the “Game of the Century” against then-No. 1 Notre Dame. It ended in a 10-10 tie and different national champions. The Associated Press, coaches and National Football Foundation, or NFF, said then-No. 1 Notre Dame were the national champions. The NFF also named then-No. 2 Michigan State national champions.

“If I had a nickel for everybody that saw the Notre Dame game, they came up to me and said ‘Yes, I saw the Michigan State-Notre Dame game,’ I’d be a rich man,” Raye said. “You think you’d be remembered for a great win, an overbearing loss or something, but people still remember the 10-10 tie.”

Raye broke barriers, becoming the first southern black quarterback to win a national championship in the midst of the civil rights movement and a pioneer for black coaches in the NFL during his 37-year coaching career.

“You can’t write the history of Michigan State football without Jimmy Raye,” said Tom Shanahan, author of the book “Raye of Light.”

“He deserves his place in the Hall of Fame.”

From the segregated South to East Lansing

Growing up in North Carolina in the 1950s and 1960s, Raye never thought of playing for any Division I colleges in the South such as Clemson, Alabama or LSU.

Those schools weren’t allowed to recruit black athletes like Raye, because of Jim Crow laws.

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

“I was good enough, ain’t no question about that.” Raye said. “It’s just that it was against the law to give a black an athletic scholarship. But I think if I was in that arena today, my skills were of such that I would have been recruited to one of those schools, definitely.”

While playing quarterback at E.E. Smith High School, Raye received offers from historically black colleges in the South.

He received only one offer from a Division I program — Michigan State.

Raye didn’t know much about MSU before the East-West Shrine All-Star game, which was a black all-star game in North Carolina during segregation.

Then-MSU assistant coach Cal Stoll gave Raye the MVP award, and Raye’s recruitment process began.

Raye said he started to follow the Spartans from that point forward — especially in his senior year in high school when MSU played Illinois in the Big Ten championship Nov. 28, 1963, which the Spartans lost 13-0.

Then-coach Duffy Daugherty offered Raye a scholarship, and he took it. Raye said he couldn’t believe it — he was going to play quarterback for a major university.

“It was almost unbelievable that I had the opportunity,” Raye said. “And then to be able to play the position, it was unreal.”

Shanahan said black quarterbacks during the civil rights movement never got the opportunity to play their own position. Instead, they would often be switched to a skill position such as running back or wide receiver.

“So Duffy Daugherty — Jimmy has said this many times — showed a lot of courage letting him play quarterback, letting him earn the job,” Shanahan said.

At the time, Michigan State was short on quarterbacks, especially when All-American quarterback Steve Juday graduated after the 1965 season, Shanahan said. Without Raye, the 1966 unbeaten season would have looked very different.

“He was very open to being a part of a team, family situation,” former MSU wide receiver Gene Washington said. “In college sports or football, you can’t win every game. But he was the type of person that … he’d always pick himself up, and return and be as motivated as he was the first time — whether he won or lost. That’s the toughness that he had.”

The Duffy effect

Daugherty knew making Raye the starting quarterback in 1966 would be controversial.

Shanahan said Daugherty got push back from fans, residents of East Lansing and boosters.

This is when Michigan State was a leader in integration with Daugherty and then-President John Hannah, who from 1957-64 was the first-ever Chairman of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, along with having one of the first black football athletes in defensive tackle Gideon Smith in 1913.

“When it looked like Jimmy was moving up to be a starting quarterback, Duffy got a lot of hate mail saying that, 'There's too many blacks on the team and we don't want a black quarterback,’ “ Shanahan said. “This is at Michigan State that's supposedly a light place, compared to what it is like at other places. But, Duffy stuck to it, gave Jimmy a chance, and Jimmy proved himself on the field in a lot of games.”

And Daugherty wasn’t just like this with Raye.

Gene Washington, Raye’s teammate and top wide receiver in 1966 with 27 catches for 677 yards and 7 touchdowns, said Daugherty made sure everybody on the team was on the same page.

“When we first met Duffy or when I first met Duffy Daugherty, he really stressed and told everybody on the team, not only black players, but he would always say, 'Hey just call me Duffy. I don't need to be called coach or sir or anything like that,’ and so that struck me right away,“ said Washington, who grew up in La Porte, Texas. “When you coming out of a completely segregated situation when you first meet a white coach and he wants you to call him Duffy, it's kind of odd and refreshing. It makes you feel like part of the family.”

Shanahan said Daugherty was able to recruit players not only through coaching seminars in the south, but by being successful on the field.

By being successful on the field, Shanahan said Michigan State was able to appear on TV more, which was limited to about one or two times back in the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1952, MSU’s second national championship under then-coach Clarence “Biggie” Munn, introduced the country to quarterback Willie Thrower, one of MSU’s quarterbacks.

Then in the 1954 Rose Bowl against UCLA, Michigan State had the most black players than any team in the Big Ten with eight. In 1956, when the Spartans and Bruins faced off, MSU had seven black players while UCLA had six.

The Rose Bowl back then was comparable to the modern day Super Bowl, Shanahan said.

“So fans in the South saw that Michigan State had a lot of black players, and if you were a guy like Jimmy Raye or George Webster or ... Gene Washington, you wanted to go to a place like Michigan State,” Shanahan said. “That was a dream school, because you knew you would get a fair chance.”

Raye said the efforts of Thrower and Minnesota quarterback Sandy Stephens, who led the Golden Gophers to the 1960 national championship, help opened the door for him to play football at Michigan State.

And to make sure Daugherty’s players didn’t get in trouble, Daugherty instituted a curfew the night before games and the night after games, Raye said.

“We were the only team in the country that had curfews the night before the game and the night after the game, because if he'd allowed us to run loose publicly, particularly run loose on a Saturday night, I probably wouldn't be sitting here,” Raye said.

But, because of the efforts of Daugherty, Raye was able to play quarterback at a D1 school.

“His vision, along with President John Hannah, to explore the segregated south and give blacks an opportunity for an education and athletics, I can't thank them enough,” Raye said. “And I think because of that, I pay every credit to them with this honor.”

“I had no intentions of coaching”

After Raye’s NFL playing career was shortened by a broken arm, he enrolled at Michigan State’s School of Education for his master’s in education.

Raye said he planned on going to law school before Daugherty asked him to join his coaching staff as a graduate assistant in 1971.

Raye said he never thought of joining.

“I had no intentions of coaching,” Raye said. “I was back (at Michigan State) working on a degree and going to graduate school, and he asked me to come out and help coach, help with the scout team and do some scouting and I did.”

At the end of the season, George Perles, who was Daugherty’s defensive line coach, left for the Pittsburgh Steelers, giving an opening to Raye, who shared the position with Herb Paterra.

After five seasons with the Spartans, Raye coached at Wyoming and Texas, before leaving to be the wide receivers coach for the San Francisco 49ers. It was his first NFL position, making him one of three black assistant coaches in the NFL at the time.

Raye said all of that could not have happened without Daugherty.

“He was very instrumental in my coaching career at the start of it, and mentoring me the early years of it,” Raye said. “Without him, I probably wouldn’t have lasted in coaching very long.”

What followed was a 37-year career as an NFL assistant coach with 10 teams. Though Raye said he would’ve liked to have been an NFL head coach, he knew the time he was in wouldn’t make it easy. He felt it wasn’t “a birthright.”

“Just like when I played quarterback, I came along when that wasn’t fashionable, and that was at the height of my career,” Raye said. “When I started the National Football League, there were only three black assistants: myself, Elijah Pitts and Lionel Taylor. As I grew through that process, the idea of hiring a black head coach in the National Football League was not something that was talked about.”

Raye said he was able to keep getting opportunities to coach in the NFL because he “could do a job.”

“Some people can get a job, some people can do a job,” Raye said. “I think I benefit from being able to do a job and I had the respect of my peers across the National Football League, and consequently I had a long career.”

Inspiring the next generation

While Raye was the offensive coordinator of the Kansas City Chiefs, he visited Howard to scout quarterback Ted White in 1999.

In the process, Raye stumbled across White’s quarterbacks coach, Pep Hamilton, who’s currently Michigan’s passing game coordinator.

Raye then made Hamilton an offensive intern on his staff — which led to a 15-year NFL coaching career for Hamilton with a three-year stint at Stanford from 2010-12 — before joining the Wolverines staff.

“The wealth of information that he provides, and a simple conversation about football, really just gave me the perspective of, I had a lot to learn and I had to work hard to learn it,” Hamilton said.

Raye also convinced Daugherty to let Tyrone Willingham, who became the first black head coach in Notre Dame football history in 2002, walk-on at Michigan State in 1973.

Former Indianapolis Colts coach and current analyst on “Football Night in America” Tony Dungy, grew up in Jackson, Michigan wanting to be Raye, Shanahan said.

Raye’s son, Jimmy Raye III, is in his 24th year in the NFL and his first season with the Detroit Lions as a senior personnel executive.

In short, he had reach, author Shanahan said.

“A lot of guys Jimmy came in contact (with), looked up to Jimmy and wanted to follow in his path,” Shanahan said. “At the same time, Jimmy was in the NFL for so long, when he would go out scouting different colleges, he’d spot a guy here or there and encourage him to go to coaching, and maybe give him a break.”

Hamilton said even Raye’s phrases rubbed off on him.

“One saying that he had was, ‘There’s a lot of different ways to get to Chicago,’ ” Hamilton said. “That’s his way of saying, ‘There are more ways to get something accomplished than just the one traditional way.’ I use that quite often.”

Hamilton said Raye never complained about the circumstances he was faced. He just focused at the task at hand.

“He never once complained about the circumstances,” Hamilton said. “He just focused on the output and the work, and being the best coach he can be and making his players the best players they can be. I try and do the same.”

Hoping he made a difference

Raye is still involved with the NFL, working on the career development panel, which is charged with improving the number of minority coaches, coordinators and general managers in the NFL.

Raye said the panel complements the Rooney rule, which says teams have to interview a person of color when filling a position.

“We find the qualified people that they claim don’t exist,” Raye said.

Raye now lives in Pinehurst, North Carolina about 44 miles from Fayetteville.

Washington said Raye is deserving of being in the Spartan Athletics Hall of Fame, and is glad Raye’s leadership style carried into the NFL.

Raye’s leadership is something Washington spotted from his days at Michigan State, as Raye was the first player to show up to practice and the last to leave.

“He’d always set an example,” Washington said. “He was always there for you.”

Raye hopes he “did a little bit” to get more black quarterbacks and coaches in the NFL and in college football.

“Clemson, Alabama, LSU and all of those teams down south, because of Jim Crow laws, wouldn’t allow black athletes to get scholarships,” Raye said. “They all have black quarterbacks now. I think, and I hope, I did a small part in opening up the minds of some of the college administrators and the people in general in the South.”