$2.7 billion.

$2.7 billion.

That’s the number of dollars scholastic institutions like MSU have lost at the hands of big banking, according to a recent study published by The Roosevelt Institute.

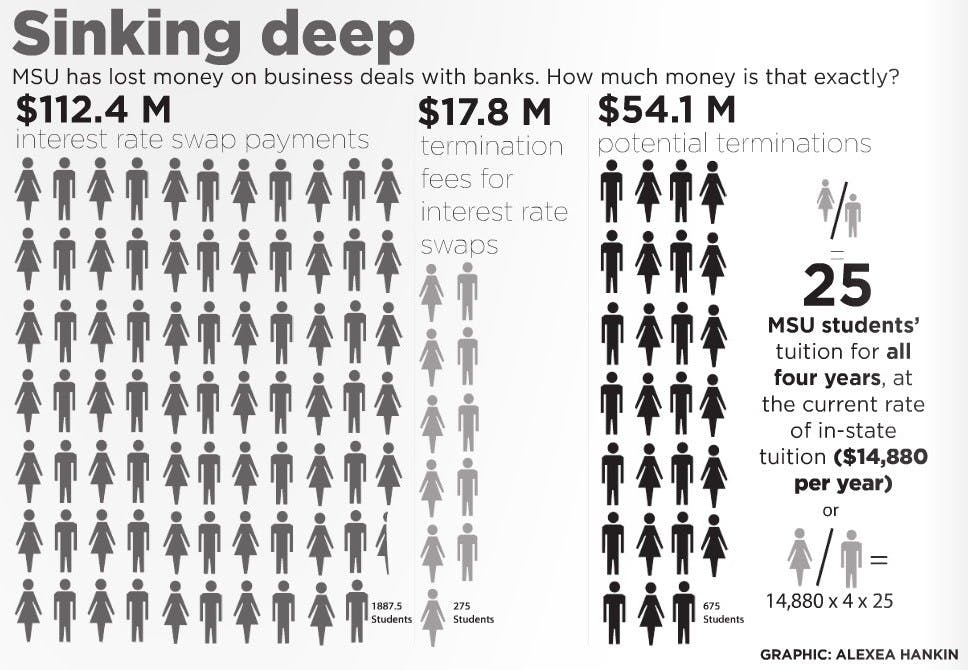

In a study conducted between 19 public and private universities ranging from Harvard to the University of Michigan, The Roosevelt Institute found MSU only contributed to about 4 percent of this $2.7 billion total. But overall, MSU has lost $130.2 million in fees from bad business deals with banks formed in the late 1990’s to early 2000’s.

Business sophomore and policy director at MSU’s Roosevelt Institute chapter Nathan Feather equated the deals, now called interest rate swaps, to gambling.

He called working with the Roosevelt Institute “eye-opening.”

“What we did in those deals is, essentially, we took a complete risk,” Feather said. “Essentially a gamble, and a gamble on whether or not interest rates would be above a certain percent. The problem is, these deals have not produced very effective results for us.”

Starting in the late 90’s MSU, alongside many other public universities across the nation, entered into these interest rate swap deals to compete with one another in the “amenities boom” across college campuses, former chapter head at the MSU Roosevelt Institute chapter and current midwest regional coordinator Mario Gruszczynski said.

To get more money flowing into the university, officials decided to take out these loans to finance big-scale projects like stadiums, cafeteria renovations and other amenities deemed attractive to future students.

Communications director for the MSU Roosevelt Institute chapter Walter Hanley said these deals looked great at the time.

They were given to universities as a realistic way to pay for big projects and get money back in the process. But they never went as planned, he said.

“Basically, there’s two ways you can finance a long-term debt budget: with a variable rate or a fixed rate,” Hanley said. “With a fixed rate, you’re always paying the same thing. A variable rate changes based on economic conditions.”

To sum it up, banks offered universities a deal. Universities pay the banks a fixed interest rate, while banks pay universities a variable interest rate, according to the Roosevelt Institute’s Financialization of Higher Education report.

“If the interest rate is really high, the university would make money,” Hanley said. “But if it’s very low, we’re going to lose money. The issue with a lot of these, is that 2008 happened, and the financial crisis lowered interest rates to basically zero.”

But the financial crisis is not only to blame for this, Gruszczynski said

“The reason the university had to turn to the financial industry for that help was in part from declining aid from the state of Michigan,” Gruszczynski said. “Higher education costs have been rising, and that’s what sort of pushed the university into this position to look to financial institutions to finance projects like this.”

Feather said before the late 90’s, deals of this nature just didn’t exist, which was part of the risk. Gruszczynski said he doesn’t believe the university did any of this on purpose—it is university officials’ jobs to responsibly handle student’s money and state endowments—but just that university officials lacked the knowledge, at the time, to realize the weight of these decisions.

“Part of this is the asymmetry of information,” Gruszczynski said. “You’ve got these financial institutions who have these very well-paid, very highly-trained professionals basically inventing these financial instruments like the interest rate swaps, and you know, we don’t have the same resources that a bank does as a university.”

Since then, the majority of the swaps have happened. Gruszczynski said the university has most likely caught on to how bad of an idea they are. MSU recently paid $17.8 million to terminate some of the swaps. The problem is, according to the Roosevelt studies, the university faces more long payments for years to come or $54.1 million in potential terminations of the swaps.

“We need to look at recourse for the university to renegotiate some of these swaps and potentially recoup some of these losses,” Gruszczynski said. “There is precedent for that happening in other situations. ... That’s the short term. The long term is, what is the role of our university and should they be relying so much on the financial industry, an institution that clearly does not have our best interest at heart as students or as a university?”

Support student media! Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

To students like Feather, who saw this data pile in firsthand and is directly affected by the swaps, said the data can be “infuriating,” especially after looking at MSU’s continual tuition increases through the years, and looking at Michigan as a whole.

“Really, this is a country-wide issue,” Feather said. “For the future of Michigan State, I think we need to make sure that, as students, we’re paying attention to what the university is doing with our money, especially with continual tuition increases.”

For the Roosevelt Institute’s future research, this information is only the first piece of what will be a larger project on mismanagement of funds. And they’re going to figure it out, Feather said.

“Though we’re able to do this research and get to the bottom of these interest rate swaps and what has happened at Michigan State and across the country, that wasn’t necessarily the only financial product that had been sold and affected the mismanagement of money,” Feather said. “This is just one product. ... And maybe we need to start paying attention to it.”