The seven green roofs on campus feature a wide variety of plant life, including from the tomatoes and melons that grow on Bailey Hall to shrubs and Sedum, a relatively low-maintenance flower that is commonly used on many green roofs.

Horticulture professor Brad Rowe spearheaded green roof research at MSU, and the growing number of green roofs on campus are largely a result of his research.

As the university recognized Campus Sustainability Week last week, green roofs and other environmentally friendly initiatives were at the forefront of campus activities, including a tour of green roof facilities.

Green roofing, past and present

Rowe first began his extensive research of green roofs back in 2000, when he began consulting with the Ford Motor Company on the best methods to use when installing a green roof on a Dearborn, Mich., assembly plant.

In consulting with the company, Rowe and his colleagues had to test methods of green roof growing, including different types of soil the plants were to be grown in, the depth needed for certain kinds of plants and what care was required.

The first green roof built on campus was not actually a roof at all but a series of platforms built at ground level to resemble the structure that might be built on a roof.

“Part of (the research with Ford Motor Company) was they wanted things tested,” Rowe said. “The only problem with that was the plant was down there (in the Detroit area) and we didn’t have control of it. … Having it here, we had total control. We started out with 8-by-8 platforms in 2001 — the first actual roof was built in 2004.”

The first full-scale green roof was built on the Plant and Soil Science Building as part of renovations done in 2004.

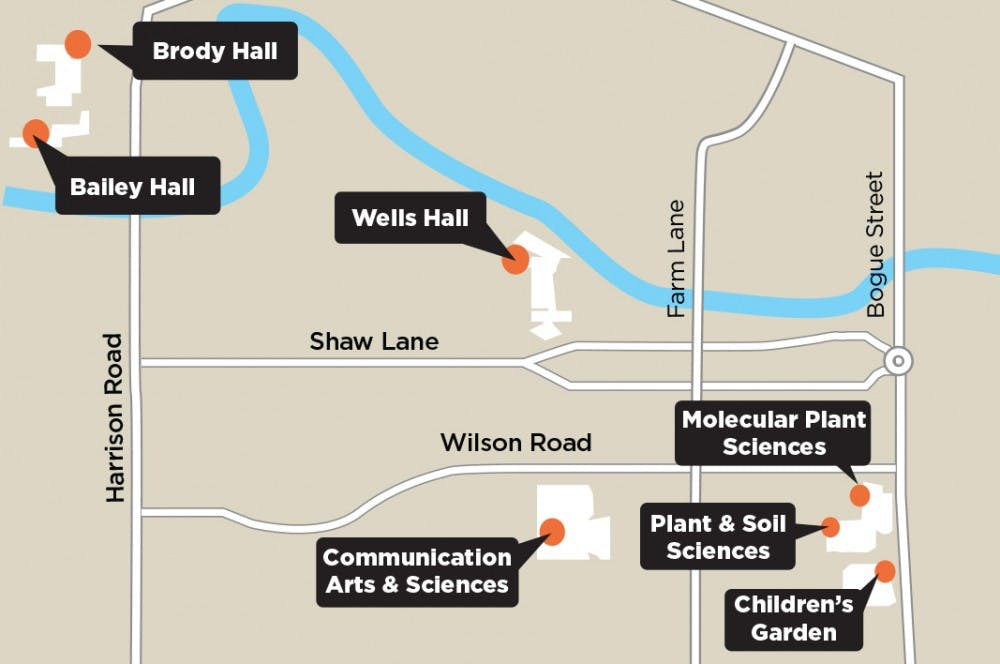

Green roofs then were added to the Communication Arts and Sciences Building, Molecular Plant Sciences Building, Bailey Hall, the Children’s Garden Outdoor Classroom, Brody Hall and most recently Wells Hall, which was outfitted with a green roof in 2012.

The 8-by-8 platforms Rowe mentioned are located at the Horticulture Teaching and Research Center.

The numerous green roofs built with the help of Rowe and the research team range in depth from 1 inch to 4 feet and in slope from 1 percent to 45 percent. They are located at heights ranging from 0 to 15 stories, and come in sizes from 3,500 square feet to 10.4 acres, according to the MSU Green Roof Research web page.

To build these green roofs, Rowe and the rest of the research team had to decide which buildings met the requirements needed to build a green roof.

The first thing to look into for a prospective green roof building is the structural load it is able to carry, said Milind Khire, an associate professor of geotechnical and geoenvironmental engineering and a member of the MSU green roof research team.

Cities and townships also set requirements ensuring green roofs do not become a health hazard should the drainage system malfunction.

In addition to meeting structural and local requirements, the next thing to consider when building a green roof is cost.

“It’s hard to provide an exact number as it depends on if it is a flat roof or a sloped roof and what needs to be changed structurally to make sure the roof meets the loading requirements,” Khire said. “The cost also depends on the depth of the green roof and expected plants species. Deeper green roofs can cost $25 per square foot or more but will require less maintenance.”

Flat green roofs usually cost about $10 to $20 per square foot, he said, while sloped green roofs are relatively expensive to build and to maintain.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

He said until green roof technology decreases in cost, it primarily will be used on industrial and commercial buildings.

Like traditional landscapes, the foliage on a green roof varies in costs depending on the specific species that are planted.

Generally speaking, living roofs are categorized as intensive, semi-intensive or extensive, hinging on the depth of the soil used and the care required.

Green roofs including trees and perennials require more care, while rooftop gardens with Sedum and mosses, such as the ones on campus, usually require less.

The benefits of going green

Adding plant life to the top of a commercial building can have numerous positive effects, including the reduction of noise, air pollution and carbon, the increase of urban biodiversity and the creation of a more aesthetically pleasing rooftop.

One of the main reasons Rowe cites for having a green roof is stormwater management.

“Stormwater is a problem because we have so many impervious surfaces, like parking lots and buildings as opposed to grasslands,” Rowe said. “When rain falls on a prairie, 95 percent of the water filtrates into the ground.”

Rowe said MSU’s stormwater system holds a limited amount of water. Limited space ultimately can lead to overflowing pipes that leak raw sewage. Green roofs help reduce the runoff, he said.

Rowe also added that certain countries, namely Germany, have stormwater runoff taxes that charge citizens based on the percent of impervious surfaces on their property.

The more impervious surfaces, the greater contribution to runoff.

Rowe said similar policies could provide people with an incentive to add a green roof to their commercial building or business.

Green roofs also lower the temperature of a building because of the constant evaporation and transpiration of water being done by the greenery. In addition to aiding in cooling, green roofs add a layer of insulation to the building.

Rowe said that, despite the long-term advantages, businesses might find it more cost effective to simply add a layer of traditional insulation.

Until more favorable government policies are put in place, such as a stormwater-runoff tax, Rowe believes that many property owners will opt for the cheaper and less labor-intensive option.

Getting their hands dirty

When it comes to taking care of the green roofs on campus, students who are members of the Residential Initiative on the Study of the Environment, or RISE, do most of the dirty work — planting, watering and harvesting the plants grown on top of Bailey Hall.

“The students have been funded by a Residential and Hospitality Services Neighborhood Collaboration Grant to study what vegetable crops, soil mixes and container types are best for rooftop farming,” RISE Program Director Laurie Thorp said. “They grew over 20 different vegetables, fruits and herbs this summer and collected yield data on the crops. They plant the seeds, water, weed and harvest.”

Although growing season now is over for RISE students, this past summer they grew a wide array of edible plants. Those plants included diverse crops such as tomatoes, cucumbers, melon, strawberries, basil, carrots, kale, chard and other herbs.

Unlike the food grown in the Bailey greenhouse that goes to Brody Square and Kellogg Center, the greens grown on top of Bailey Hall are used by the RISE students in monthly cooking events where students gather to cook ethnic dishes with one another.

This past Friday, the RISE students cooked two African dishes with help from students from Malawi and Rwanda.

A green future

Going forward, Rowe and the research team are looking to expand the number of green roofs on campus and also raise awareness and acceptance of rooftop gardens as part of the university’s overall sustainability platform.

The next phase of the plan is to install a green roof on the bus shelter in front of the Human Ecology Building, Rowe said. This shelter would be equipped with educational material for viewers.

“I don’t see any negative to it other than initial cost, but the return on investment comes for any green roof,” Rowe said. “If there were more green roofs where people could see, they could ask questions and learn more about them.”

And learning about green roofs leads to the creation of more green roofs, he said.

According to an annual green roof survey done by greenroofs.org in 2012, the North American green roof industry grew 24 percent during 2011.

Although this might seem like a large increase, the industry was very small to begin with. In keeping with this national growth, Rowe also suggested that new buildings on campus should include a plan for a green roof to positively impact campus sustainability.

“Green roofs are becoming a bigger thing outside of MSU too,” Matt Kimmel, a landscape and nursery management sophomore said. “I know Chicago has many green roofs — it’s a new thing for people. … It’s not something that you see everyday and I would hope that people would like to come out and see this unique feature we have on campus.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “Growing green” on social media.