To many people, former East Lansing Councilmember Mary Sharp meant a lot of different things.

She was a participatory councilmember, engaging other members on various issues. She was engaging with the city staff, routinely spending time at different Christmas Eve parties toasting all the East Lansing City workers.

And, in the case of Councilmember Kathleen Boyle, she was a matchmaker, as she introduced her parents to each other.

But even Boyle knows the real impact Sharp had on East Lansing was through her human and civil rights work on council.

Sharp served on the council from 1965-77 and passed away in February 2006.

Seven years after her death, a sculpture was planned in her honor and placed outside East Lansing City Hall. As of March 22, $2,500 still is needed to fund the project, which is scheduled to be installed at the end of the summer.

The sculpture idea came from former Ingham County Circuit Court Judge Michael Harrison, who said he wanted to honor Sharp for her work to introduce an ordinance banning discrimination against racial minorities that kept them from buying and renting homes in East Lansing.

“(She was) literally an individual who left footprints which were of a significance,” he said. “I thought it was somewhat inappropriate in a way she had not been recognized more than she had.”

A more welcoming community

Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed into law, former MSU Athletic Director and East Lansing resident Clarence Underwood came to Michigan from Alabama. He had been accustomed to discrimination, but didn’t expect he would find any in a city like East Lansing.

“You would have thought back then … That there wouldn’t be that kind of problem in this city,” he said. “But there was.”

Underwood, who’s lived in and out of East Lansing since 1955, recalled a time when the color of his skin came between him and finding a home in the city.

“(I had) tried to rent before, and I was turned down by several different owners,” he said, adding eventually a friend helped him find a place to live. “It was impossible to rent a home in East Lansing at the time.”

Former East Lansing Mayor George Griffiths, who served with Sharp as both a councilmember and mayor, said Underwood’s concerns were a reality the council, led by an enthusiastic Sharp, fought to end.

“The realtors had an agreement amongst themselves they wouldn’t show any houses to a black family,” he said. “(The council was) very active in protest.”

Griffiths said he heard a negative response from some realtors in the community, including a realtor couple who argued to him that, “We should choose who we want to live in our community.”

To Underwood, the ordinance helped make East Lansing the diverse community he hoped it would be.

“That legislation really did a lot in terms of opening up East Lansing for minorities, blacks in particular,” he said.

Mayor Pro Tem Nathan Triplett said without Sharp’s work to pass the anti-discrimination housing ordinance, East Lansing might not be the city it is today.

“Mary saw discrimination in our community and saw people who weren’t being involved in community life because they didn’t feel welcomed,” he said. “She really took a stand to make sure that she built a foundation to make East Lansing the welcoming community it is today.”

Sculpting a future

Harrison said he thought of the sculpture idea several years ago while he was looking to recognize Sharp for her civil rights work.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

The Sharp family was enthusiastic about the idea once they began looking at the quality of the artists submitting sculpture proposals to the East Lansing Arts Commission.

Mary Patricia Sharp, Sharp’s daughter, said the family was touched Harrison wanted to honor her by having a sculpture built.

A selection committee was put together to select an architect from across the country. Richard Taylor was selected and approved by the East Lansing City Council in December 2011.

“Her personality and her work really influenced me to apply for this competition,” Taylor said. “I was really impressed with the person she seemed to be.”

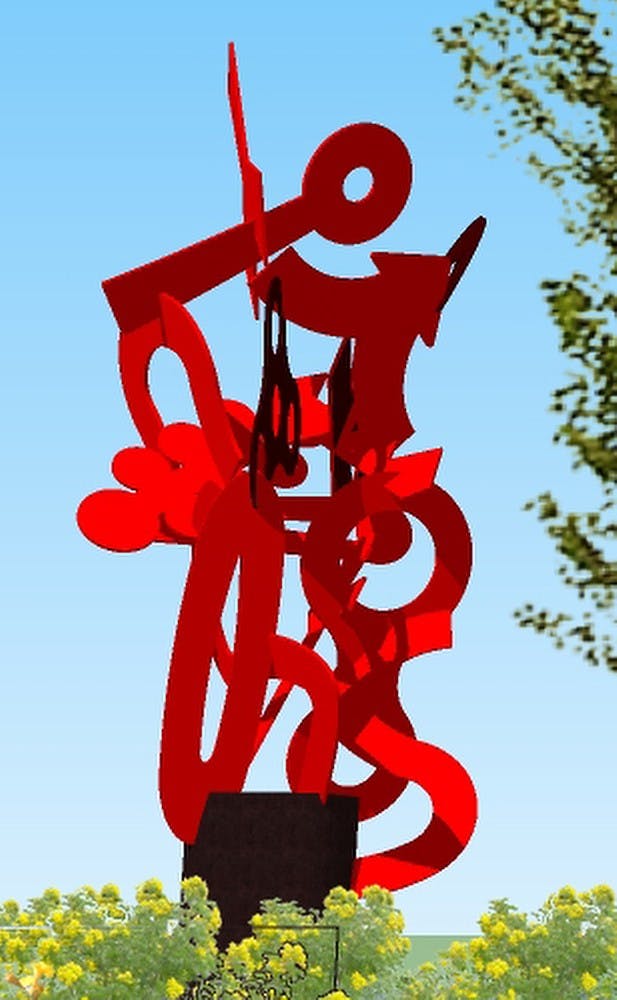

Taylor said he designed the sculpture in a way to represent the work Sharp did with diversity and civil rights. The sculpture is a cluster of arrows, curving lines and a smattering of circles twisted together and painted a fresh shade of bright red.

“I thought it might be appropriate to design the sculpture that showed the many diverse elements could live together in harmonious ways in one piece,” he said. “A diverse number of shapes being united in one sculpture, that being a metaphor for the diversity in the human population.”

Mary Patricia Sharp said the sculpture design is animated — just like her mother was.

“Most people remember my mother with a remarked sense of humor and energy,” she said. “Everybody I’ve shown it to said he nailed it.”

Social relations and policy senior Paris Wilson said the sculpture will showcase the impact one person can have on a community. Wilson is president of Alpha Phi Alpha, which has a history of promoting black student rights on campus.

“It’s kind of that reminder how important (it is) for one person to stand against the norm and stand for something that’s right,” he said.

Discussion

Share and discuss “Sculpting a more equal future” on social media.