“There are definitely a lot of hurdles to jump through,” he said.

Because of changes made this year to the Department of Human Services Food Assistance Program, VanKirk was among the few students who were able to prove they were really in need of assistance.

With the semester kicking into gear, nearly 30,000 Michigan students who lost their cards in the spring are faced with the decision to either reapply for assistance or turn to alternative options.

Changing Bridge Card requirements by no longer accepting student status as a qualifier saves Michigan about $75 million annually in taxpayer dollars, said Sheryl Thompson, acting deputy director of field operations at the Department of Human Services, or DHS.

“As we’re looking at our budget, this was something we needed to do in order to make good use or the taxpayer dollars,” Thompson said. “We are just enforcing the federal guidelines.”

Burning bridges

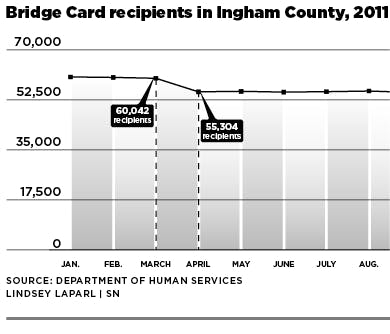

In Ingham County alone, the total number of food assistance recipients decreased by nearly 5,000 from March to April, when the changes first were implemented. This drop reduced the amount of total payments by more than $880,000 during the same time period.

“Prior to April, the fact that students were in college allowed them to receive assistance,” Thompson said. “That is no longer the case.”

Under the new guidelines, students attending college must be mentally or physically unfit for a job, working at least 20 hours per week or caring for a child to be eligible for food assistance benefits, she said.

In addition, Thompson said individuals or households applying for the card also will notice a more demanding application process, requiring additional forms of verification to prove their need.

Applicants must provide state-issued identification, lease or shelter verifications and the last 30 days of income and bank statements to prove their eligibility. They also cannot have more than $5,000 in assets or a vehicle valued at more than $15,000, she said.

“We don’t have the funds to help everyone,” she said. “We want to make sure that we can extend a helping hand to any citizen who is truly in need.”

Struggling for aid

Only weeks after receiving his new Bridge Card, VanKirk said he received a letter from DHS stating he had to provide a bank statement within a few business days to prove his assets or his benefits would be discontinued.

“They’re always threatening to cut you off no matter what you do,” VanKirk said. “It’s always uncertain whether I’ll even have the card tomorrow or not.”

Even after proving he was eligible, VanKirk said it is hard to escape the negative stigma surrounding the cards.

“I’m tired of people labeling the program as a welfare system when that’s not the case,” VanKirk said. “Food assistance was made to assist low-income individuals in making healthy purchases.”

With the burden of tuition and university-related costs, rent and a car payment, having a Bridge Card has taken away some financial stress while allowing him to make more nutritionally adequate decisions.

Without the card, VanKirk said his health would suffer, leading to more problems further down the line.

“I don’t need the state’s help to buy Ramen Noodles,” VanKirk said.

Support student media!

Please consider donating to The State News and help fund the future of journalism.

“Could I live on them physically? Yes. But would I be healthy? No.”

Bridging the gap

For second-year graduate student Erin Sutton, obtaining a Bridge Card has been a constant struggle.

With three attempts in the past two years, Sutton still has not been approved for food assistance benefits, which she said really would help improve her financial situation.

“It gets discouraging when you’ve applied this many times,” she said.

With graduate school classes, an assistantship and a part-time job, Sutton said she has been doing everything she can to make ends meet.

“It almost feels like I’m being penalized for doing everything right — for going to school, not having a child so early in life and taking care of my health,” she said.

Studio art sophomore Brittany Moses also was denied for food assistance because she lives on campus.

“For myself, I do need the extra assistance for food and stuff — I’m not working right now.”

Despite her long hours at work and commitment to school, Sutton and her partner still live in a constant state of anxiety over their financial burden. They have taken in another roommate to help pay for rent.

“My budget is pretty tight,” she said. “I don’t feel like I’m going to starve, but it’s definitely stressful to think about.”

To help out, Sutton said she has recently started going to the MSU Student Food Bank, an on-campus resource that provides support with groceries to students in need.

“It’s been really helpful,” she said. “It’s not necessarily always the food that I would choose … but it puts food on the table, so I can’t complain.”

MSU Student Food Bank director and doctoral student Nate Smith-Tyge said the number of students turning to the food bank for assistance recently has increased by about 40-50 new clients.

“We have noticed a pretty sharp uptick since the beginning of the fall semester,” he said.

“I don’t know if it’s directly related to the loss of Bridge Cards, but it’s definitely a possibility.”

With support from the MSU community through monetary and cash donations along with strong partnerships with the Mid-Michigan Food Bank and various on-campus organizations, the program is able to cover the influx of students, Smith-Tyge said.

“So far, we’ve been able to successfully meet the students’ increased demands,” he said. “If this trend continues, we will have to increase our efforts.”

Despite the constant pressure that comes along with her enrollment at MSU, Sutton said her hard work and sacrifices eventually will pay off.

“I have good job prospects for when I finish school,” she said. “There is hope that this won’t be my situation forever, and that helps me get through this.”

Discussion

Share and discuss “Making ends meet” on social media.