One way universities have tried to help the underprivileged is through what is commonly called affirmative action, which in higher education means allowing an applicant’s race or ethnicity to be taken into account during the admissions process to offset structural disadvantages that might come from attendance at lower-performing high schools.

This was ended in Michigan in 2006 and could be ended across the rest of the nation should the U.S. Supreme Court make that ruling this fall, allowing for some creative workaround by the admissions office to ensure a campus that is racially and economically diverse.

However, retention of students who were helped with the admissions process is significantly lower, prompting the university to take steps to ensure it helps students through their entire college career and not just at the starting gate.

Michigan’s ban

Prohibition of any kind of affirmative action in Michigan public universities’ admissions process was put in place by Proposal 2, a constitutional amendment passed in 2006 by a voting majority.

“The University of Michigan, Michigan State University, Wayne State University, and any other public college or university, community college, or school district shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting,” the amendment reads.

This makes Michigan one of eight states to outright prohibit taking race into account during the college admissions process.

Currently, MSU officials conduct a “holistic review” of each application, director of the Office of Admissions Jim Cotter said, although the review, by law, excludes race, ethnicity or gender from the deliberations.

“In terms of the holistic review process for Michigan State and at the (public) institutions in the state of Michigan ... those three factors cannot be considered when reviewing one’s admissions credentials and making an admissions decision,” Cotter said.

Black Student Alliance president Myya Jones said, although affirmative action should never have been in place if it was a perfect world, it was necessary due to past racial discrimination.

“It was a good thing that should never have been in place, but just knowing our history in the U.S. ... paths should be put in place to increase the admissions of minorities on campus,” Jones said.

Ensuring diversity

When admissions officers review an application, race, ethnicity and gender are hidden from the officer, although Cotter said sometimes the name can give away certain details.

This does not mean MSU has no way of ensuring a diverse applicant pool.

Although Cotter said he didn’t consider it a workaround, admissions can target areas with high schools who use a less rigorous curriculum, or first generation college students, in order to ensure a diverse campus. This means admissions looks at more than just a student’s grade point average or ACT scores when determining acceptance.

Admissions can also actively recruit persons of color to apply or target regions where high school graduates wouldn’t think they’d be able to attend MSU, either due to their grades or their financial situation.

The admissions report for 2015 has not yet been published, but the data for 2014 shows admissions is successful in that regard as 24.1 percent of the entering class were persons of color — or 1,613 of an entering class of 7,842.

Retaining those students and ensuring high graduation rates is the challenge the university now faces.

Dorinda Andrews, a professor in the African American and African Studies department, said she was part of a committee to look into why students of color are underperforming at MSU.

“What the removal of affirmative action has done is not just decrease the number of students of color that come to MSU,” Andrews said. “But once they are here there are not the necessary programs in place to ensure their academic retention.”

Retention rates

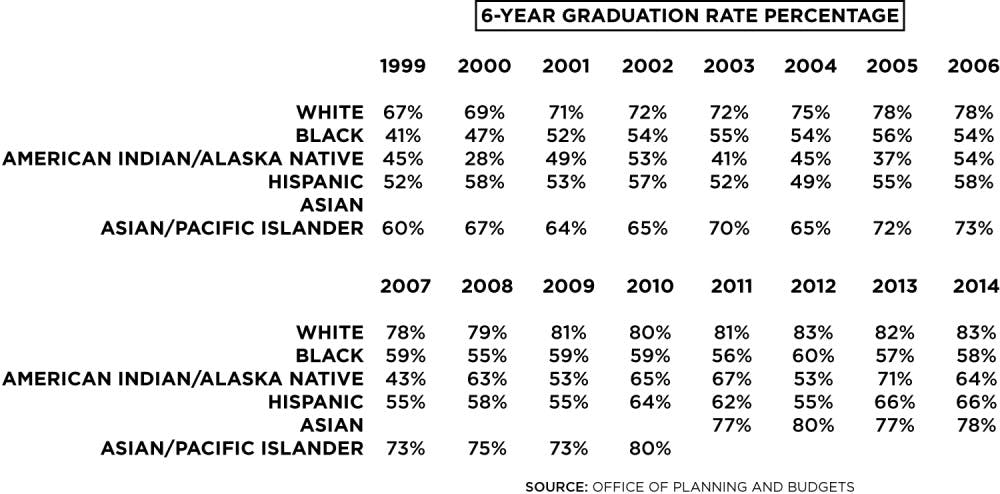

The campus-wide graduation rate is 79 percent over six years, the standard time frame. White students have the highest graduation rate on campus, with 83 percent of white students graduating in six years in 2014. Graduation rates for students of color generally sit lower, sometimes significantly so.

Black students have the lowest, with a 58 percent graduation rate. Other ethnicities include American Indians with 64 percent, Hispanics with 66 percent and Asians with a 78 percent graduation rate.

Another important distinction includes whether or not those rates have been increasing over the last 15 years.

Although graduation rates for the university as a whole have increased from 64 percent in 1999, the black graduation rate has more or less stagnated. The rate increased steadily from 1999 to 2005, beginning at 41 percent and then stagnated in the mid-to-high 50s over the last decade, reaching as high as 60 percent in 2012.

Cotter said many students of color face a wholly different set of challenges when attending a university and it cannot simply be reduced to one problem or another.

Doug Estry, the associate provost for undergraduate education and dean of undergraduate studies, said although comparing students of color graduation rates isn’t the standard by which MSU judges itself, the rate is better at MSU than at other universities. According to collegemeasures.org, the only institution surpassing MSU in Michigan is the University of Michigan.

“Our graduation rates are not where we would like them to be for underrepresented students, although when you compare us ... to other institutions we do very well, but that isn’t to say we’re not trying to be better,” Estry said.

More can be done

MSU tries to engage students both before and during their time at MSU by recruiting students of color and making sure their college transition is smooth, although many programs focus on the student body as a whole and not any particular minority group.

“There are a lot of resources being focused on helping students, particularly freshmen and sophomores, really get their feet on the ground and become successful here,” Estry said.

Jones said many advisers have difficulty connecting with students of color and, as a former resident adviser, she saw racism and racial slurs directed at black students by other students. To a large degree they don’t feel welcome on campus, she said, causing many to fail to complete their degree on time or at all.

She said although the university isn’t doing anything wrong in tackling this problem on campus, they could definitely be putting in a lot more effort. Increasing the number of intercultural aides could benefit students, since currently not every floor has one, she said.

“In recent times, based on what I heard before I got here, Michigan State has been doing a better job,” she said. “But they can always do better and it’s never just settled with, ‘Oh, are we getting minorities in here,’ but are we retaining them, because (MSU is) not retaining them.”