Sept. 27 was the day that all eyes in the sporting world turned to the Big House.

A hot button issue came to a head in an ugly way, as Michigan sophomore quarterback Shane Morris was sent back into a game against Minnesota that was already out of hand for the Wolverines late in the fourth quarter.

The problem was that it appeared as though Morris had a concussion.

After taking a hit, Morris went out of the game stumbling, showing signs of a concussion in a sports era where knowledge about the brain injury has made it unacceptable to put athletes on the field when a concussion is possible.

The fallout and criticism of head coach Brady Hoke and Athletic Director David Brandon has put all football programs and their concussion protocol under the microscope, including Michigan’s rivals down the road in East Lansing.

Increased knowledge

Concussions have always existed in sports, but with more research being done on brain injuries over the past decade, sensitivity has increased.

MSU Athletic Director Mark Hollis said every sport has either a trained physician or a neurologist on the sidelines who decide whether or not a player will play or not. For the MSU football team, that neurologist is Dr. David Kaufman.

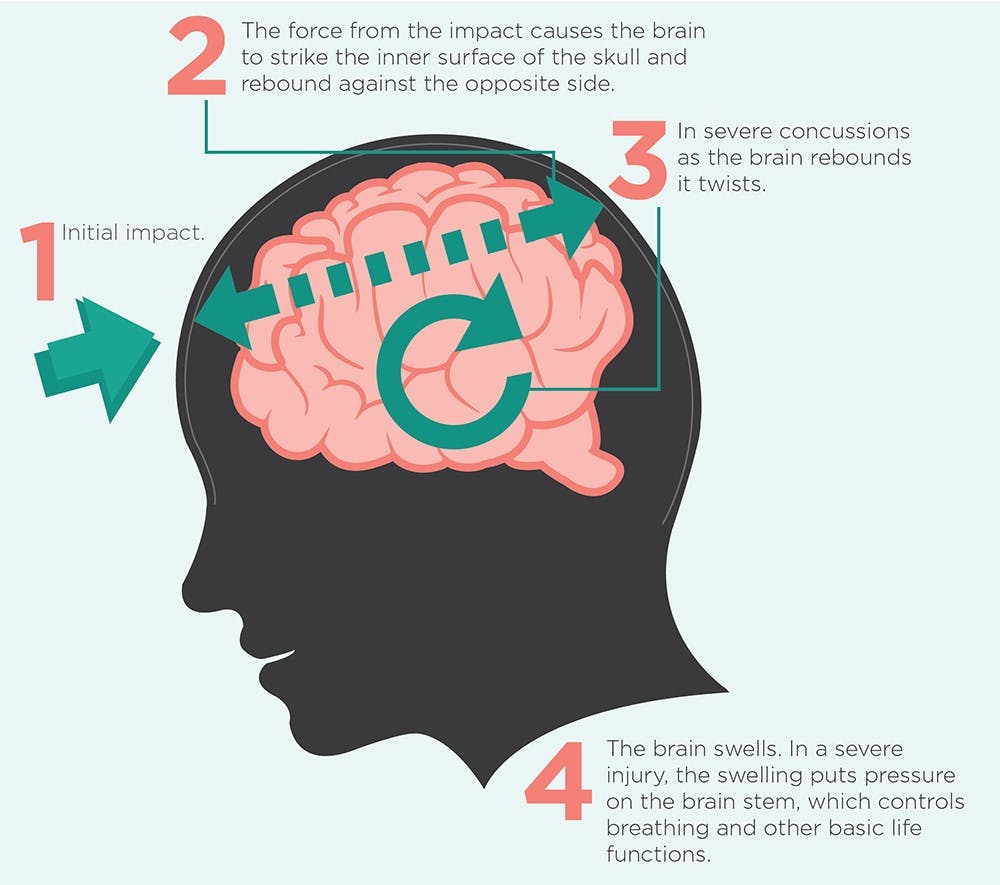

Kaufman, the head of the neurology department at MSU, said the symptoms of a concussion include dizziness, headache, memory loss, nausea and vision issues.

According to research from Kaufman, only about 9 percent of those concussed lose consciousness.

“The appropriate amount of time to come back from a concussion is specific to every person and situation,” he said in an email. “We typically use a protocol that employs a graduated return to play and the classroom based on being back on their baseline.”

Kaufman said although concussions affect everyone differently, it is dangerous for anyone to play through a concussion.

“A student athlete may have a slower response time and cognitive or vision issues,” he said. “There is a phenomena called second impact syndrome. It is quite rare, but it is theoretically possible that accelerated brain swelling can occur with a second impact soon after the primary concussion.”

According to a survey from Cleared to Play, an organization that does research on brain injury, 50 percent of second impact syndrome cases result in death.

With one concussion impact, however, Kaufman said most athletes will see improvement in symptoms within one to seven days and not see any lingering effects.

MSU’s protocol: Mark Dantonio

The situation at Michigan made national headlines, and seemingly everyone has weighed in on the issue. Head coach Mark Dantonio also weighed in on MSU’s protocol for head injuries.

“As a coach, I’ve sat in on 3 1/2 hour meetings,” he said. “We’re not going to put anyone in the game that we think is at risk. We establish a baseline for every player as soon as they walk in the door.”

Those baseline tests are put in place to see what a player’s cognitive function is before a concussion, so that if a suspected concussion occurs the player’s function can be tested again.

Dantonio said another test the program installs is an impact test. The impact test is used for after a player is diagnosed with a concussion, and tests when a player should be allowed to return to action.

“That impact test basically talks about the relevance of the concussion,” he said. “I know the younger a player is, even a true freshmen, it takes them longer to get over a concussion than a fifth-year senior. So there is a correlation between age and when someone should come back to the game.”

Dantonio said even when a player is cleared to play, the process of getting that player back on the field doesn’t happen immediately.

“We always start players with light exercise and see how they handle that,” he said. “That’s our policy, and I think our doctors as up to date on it as they can be but concussions, you know, there is a gray area because players want to continue to play.”

Dantonio said he believes MSU’s protocol is up to date. He also said he believes the decision shouldn’t always be left to the player.

“You try to educate them, but at the same time, having played college football, there are times when you hit someone and you’re stunned,” he said. “You’ve got to clear your head, and at the same time players want to play. A lot of times they’ll think they can stay in and they don’t tell you (about their symptoms).”

MSU’s protocol: Mark Hollis

Athletic director Mark Hollis understands that players want nothing more than to play, as he played high school football and was recruited by Vanderbilt. As an administrator, he also said he understands his role is to keep players safe at all times.

“The key with football is to not put the decision in the player’s hands,” he said. “Not because of a lack of trust, but because we know that player’s desire to play.”

Communication seemed to be one of the issues at Michigan, while Hollis never referenced the situation at Michigan directly, he said he wants communication between doctors, coaches and players to be the most important part of their protocol.

“Your primary role (as athletic director) is to ensure that there are sound principles of communication in place,” he said. “It’s critical as an athletic director to know what’s going on and where everything is going.”

Hollis said every football game has a neurologist and multiple trained physicians present because they are the only ones who can make an accurate diagnosis.

“You’re not in a position where you have the student athlete make the diagnosis,” he said. “At the end of the day athletic directors, coaches and student athletes are not doctors.”

MSU has also noticed improvements made to protocols of other Big Ten programs and are beginning to implement them. Northwestern has had a doctor in the press box for multiple years to serve as another set of eyes to help diagnose when a concussion occurs.

Hollis has decided to install this change as well. Following the Michigan-Minnesota game when Shane Morris was let back into the game after an expected concussion, MSU started to put another set of eyes in their press box.

Nebraska liked the idea as well, and they asked if they could put a doctor in the press box when Nebraska visited East Lansing on Oct. 4. Hollis obliged and put the Nebraska and MSU doctor next to one other.

“Nothing is perfect, but the more we can do about observation and communication, the better,” he said. “We really expanded one set of eyes into multiple sets of eyes.”

Spartan Stadium is one of the only facilities in the Big Ten with X-ray capabilities according to Hollis, which is something he said helps with the efficiency of the protocol at MSU.

“I think we have as good a procedure as anyone in the country,” he said. “Ideally you want the concussion analysis to come from a trained physician.”

The protocol depends on the sport. In football, the athlete is examined by a trainer first, which follows with a look from Kaufman. The athlete is looked at with an X-ray machine and after that the coach is informed of the player’s status.

Hollis would not comment on the specifics of the Michigan situation with Shane Morris and what he would do as an athletic director in that scenario.

“It’s hard to do a comparison without more information,” Hollis said. “I don’t want to put myself in a situation to compare myself to that situation.”